03 june 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

Between control and surrender, function and fiction – new sculptures by Jaehun Park

"I often felt like a kind of god, but with something still missing, something tactile," says Jaehun Park about the motivation behind his new sculptures. In recent years, Park has made a name for himself with video work, but for his current show, Shifting Realities at Bradwolff & Partners, he has returned to making sculptures.

Shifting Realities can be seen at Bradwolff & Partners until 21 June.

There’s something flawless about Jaehun Park’s video work, from a block of ice hanging in a strap and slowly melting while the water is neatly collected in a steel bowl to a branch from which water steadily flows. The physical impossibility and flawlessness make clear that you’re looking at computer-generated work, yet that same perfection keeps you mesmerised. After all, if water can flow from a branch, anything is possible. "You feel like a kind of god when creating the work because with a digital piece, you have full control over the outcome." They tell a story you partly recognise, yet can’t quite place due to a lack of context.

A different approach

Jaehun Park (South Korea, 1986) was educated as a painter and sculptor in Seoul, the capital of South Korea, and came to the Netherlands in 2018 to do a Master’s in Artistic Research at the KABK. He initially wanted to continue making sculptures, but that proved difficult. "I’m inspired by artists like Marcel Duchamp and like to use ready-mades in my work. So, I looked for discarded items, but quickly discovered that people in the Netherlands treat belongings differently. Little is thrown away and there’s a much larger second-hand market."

In addition to a lack of materials, the 2020–2021 lockdowns forced Park to adopt a different working method. He couldn't access his studio for around a year and therefore shifted his work to the digital domain. He soon discovered it was teeming with ready-mades, often uploaded by architects and game designers, but also by students. Plants, TVs, chairs, sofas, pans—virtually every object has a digital counterpart that is freely available.

Simulations

"A nice side effect of the lockdowns was that I had all the time in the world to learn how to work with 3D rendering tools. I spent hours watching YouTube tutorials," Park explains at the gallery. "I learned how to fine-tune everything, from the amount of wind present and rate at which a block of ice melts at a certain temperature to the way a branch twists or how fast water flows—until an interesting image emerged."

Park calls his video works simulations, not animations. With animations, you animate 24 frames per second. With simulations, the work happens upfront: as the creator, you set the parameters and then the computer calculates the outcome.

Control is also what his work is all about: the relationship between humans and nature. After seeing several of Park’s works, you notice that each one features one or more natural phenomena: the flow of water, melting ice, wind and fire. "In my work, I show how humans influence nature and vice versa. As humans, we have little control over nature—climate change aside—but in the digital domain, that control is total." As such, you can view the simulations as scenarios for a time when humans have complete control over nature.

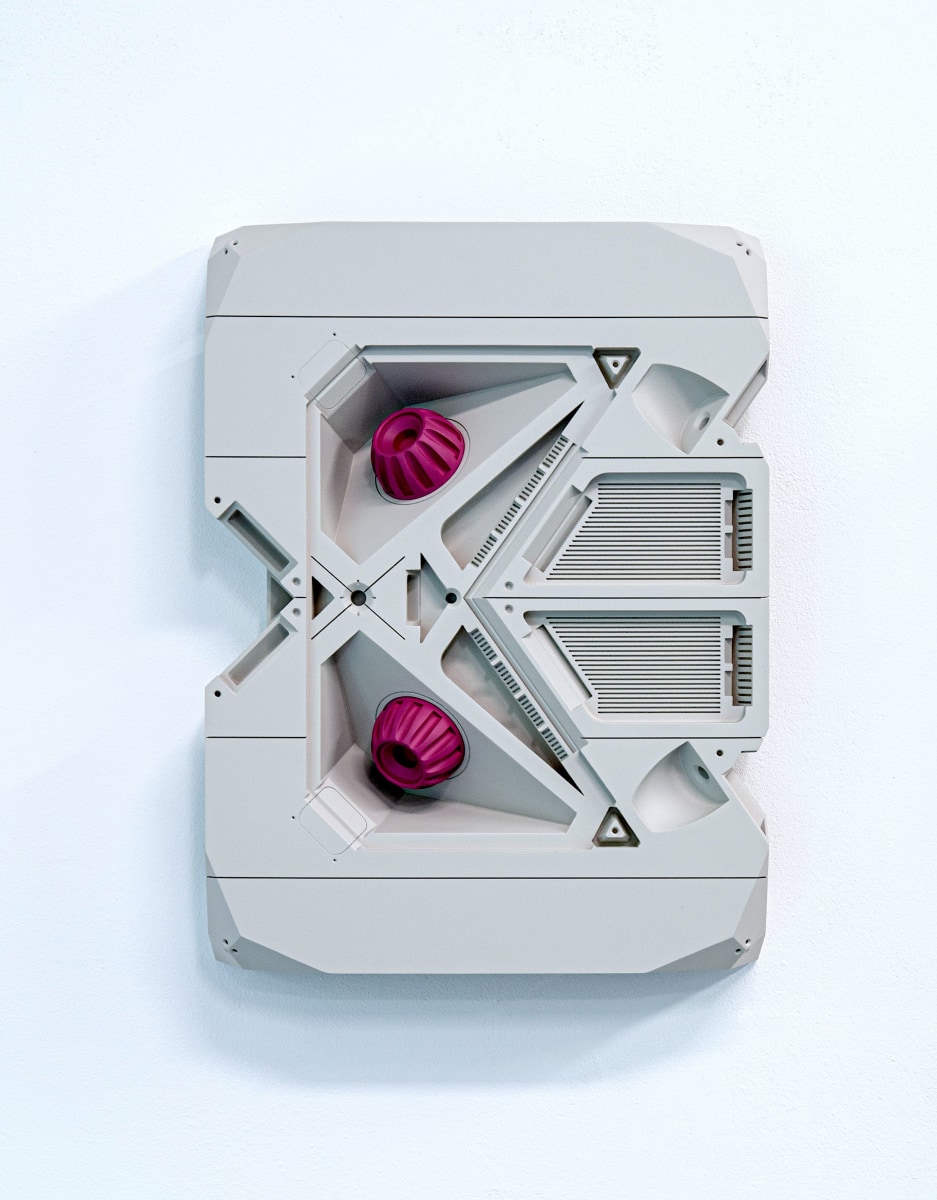

Jaehun Park, Inner core, 2025, engineered polymer, 37,5 x 28,1 x 11,5 cm, Bradwolff & Partners

Futuristic, functional and military

Although Park enjoyed having total control, he still felt something was missing, something tactile. Nearly two years ago, he began a new series of sculptures, now on display in Shifting Realities. The working method for the sculptures is the exact opposite of his video work, Park explains. "My video work originates in reality and is digitally executed. These sculptures are executed in real life, but conceived on the computer."

The works measure no more than 40 by 30 cm and look like they escaped from a sci-fi series. Park plays with visual languages from the military world, science fiction and interface design. The pieces appear futuristic, functional and militaristic. They are clinically white and grey with hues of fuchsia, mint and teal.

The sleek geometric patterns, screw holes and ventilation notches suggest that the sculptures have a clear function. But Park leaves that function ambiguous. These are objects without a narrative. This in turn prompts viewers to speculate about their possible use and to think in terms of future scenarios.

Jaehun Park. Launcher, 2025, engineered polymer, 37.5 x 28.1 x 6.8 cm, Bradwolff & Partners

Launcher , for example, looks like a component of a futuristic military weapon system: a module, a weapon interface, a link between human and machine. Made from polymer and finished with surgical precision, it resembles an industrial object, an aerodynamic form with hidden functions. The object is closed yet tense, as if ready for deployment—like a loaded gun. As the title suggests, Launcher is not an endpoint, but a starting mechanism.

These new sculptures are also about control in a sense—or at least rely on the aesthetics of control. Launcher is a sculpture as a tension field: between function and fiction, between control and surrender.

Jaehun Park, Bradwolff & Partners

Propaganda Machine

On the wall opposite Launcher, Inner Core and Astronaut Maneuvering Unit hangs a fourth new sculpture, one that indirectly references the geopolitical tensions between North and South Korea. Propaganda Machine is loosely based on the military loudspeakers in the demilitarised zone (DMZ) between the two countries. Through them, both sides bombard each other with propaganda. The sound can be heard a long distance away—a single speaker covers around 20 kilometres. The military and geopolitics are never far away in South Korea, says Park, who served two years of military duty.

Without this background knowledge, you simply see a dark orange form cast in engineered thermal polymer, a heat-resistant material often used in mass production. Again, the question arises: are we looking at control or powerlessness? The sculpture appears sleek and powerful, but it is a form of power that is being challenged and tested. There is a certain discomfort expressed in the sharp edges, grid-like surfaces and suggestive openings.

This also applies to the bird figure in the centre of the sculpture. Is it an American eagle, phoenix or a totalitarian symbol? Propaganda Machine becomes a layered object, an ideologically charged device where hope, fear and technology converge.

Jaehun Park. Propaganda machine, 2025, engineered thermal polymer, 37.5 x 28.1 x 8.5 cm, Bradwolff & Partners