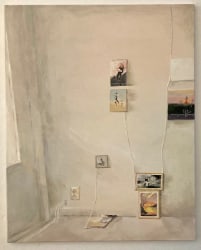

In every drawing or small painting, we see how the movements of the brush

are placed around the motif of the image. That’s where its articulation begins as

well. It happens in a very circumspect manner — partly because, not infrequently,

there exists a certain ambiguity as to what the motif actually is. Is this a volume of

some object, or its outline in fact, or when several objects are involved (in a scene)

mainly the intervening spaces or even the shadows cast by the objects? When I

look at, and nose about in, the work of Heske de Vries, I see (basically as a manual

constant) how the motif is gradually and carefully touched on and explored by

the handwriting itself — and by the motion of that manual process. A motif is, in

principle, a motionless object (a vase of flowers on a table, a close-up of a floral dress)

but there is always suggestive space around it, in all directions. And the brush moves

in that space, giving rise to form and color. Usually the motif is simple or even vague

and unsteady in form. It has to be there, since some direction has to be found for the

movements of the brush, which might otherwise disappear. This can be compared

to a stream, where a stone doesn’t really disrupt the flow of water but does leave a

discreetly meandering trace of itself: a motif (every aspect of it) likewise gives the

brush a kind of guidance, while at the same time the brush, too, articulates the motif,

as though it had never been there entirely from the start or was merely developing.

R. Fuchs

are placed around the motif of the image. That’s where its articulation begins as

well. It happens in a very circumspect manner — partly because, not infrequently,

there exists a certain ambiguity as to what the motif actually is. Is this a volume of

some object, or its outline in fact, or when several objects are involved (in a scene)

mainly the intervening spaces or even the shadows cast by the objects? When I

look at, and nose about in, the work of Heske de Vries, I see (basically as a manual

constant) how the motif is gradually and carefully touched on and explored by

the handwriting itself — and by the motion of that manual process. A motif is, in

principle, a motionless object (a vase of flowers on a table, a close-up of a floral dress)

but there is always suggestive space around it, in all directions. And the brush moves

in that space, giving rise to form and color. Usually the motif is simple or even vague

and unsteady in form. It has to be there, since some direction has to be found for the

movements of the brush, which might otherwise disappear. This can be compared

to a stream, where a stone doesn’t really disrupt the flow of water but does leave a

discreetly meandering trace of itself: a motif (every aspect of it) likewise gives the

brush a kind of guidance, while at the same time the brush, too, articulates the motif,

as though it had never been there entirely from the start or was merely developing.

R. Fuchs

Artworks

Articles

Media

Highlights

Recommendations

Collections

Shows

Market position

CV

Media

Heske de Vries explains ‘Scenes and Squares’

About

Suikerspinzachte ‘metafysische’ pleinen

Hoe lang kun je de blik laten dwalen, over een oppervlak van niet meer dan 40 bij 50 centimeter? Als dat het schilderij Square with Glass buildings van Heske de Vries is, dan kan dat een hele poos zijn. In gebroken wit, zachtroze en lichtbruin schilderde De Vries een groot, open plein. Het zou Parijs kunnen zijn, Wenen, of Madrid? De mensen op straat zijn aangegeven met piepkleine streepjes zwart. Opvallend: geen auto’s. Geen hectiek. Vooral heel veel leegte, de suggestie van gebouwen op de achtergrond en prachtige zachte, donsachtige suikerspinkleuren.

De Vries schildert al een aantal jaar pleinen. Die van haar zijn niet minder vervreemdend dan de iconische ‘metafysische’ pleinen van Giorgio De Chirico, die daarop objecten uit verschillende tijden combineerde en loszong van hun tijd. Zoiets lijkt ook te gebeuren op het andere plein dat nu te zien is bij galerie Cokkie Snoei in Rotterdam. Rechtsonderin staat een monumentale zuil, die in de ruimte lijkt te zweven. Net als bij het andere plein is het moeilijk te bepalen waar, en wanneer dit plein is. Het maakt dat deze pleinen van De Vries eerder om ideeën en gevoelens gaan, dan om de pleinen zelf.

Het andere werk van De Vries heeft dezelfde romantische zachtheid van kleur. De uitvoering is dromerig, de onderwerpen zijn alledaags: een hand die kersen oppakt, een tak met bloesem, wat oesters en een plant in een pot die (toevallig?) met de takken ander werk van De Vries verbindt.

Nu lijkt het misschien wel heel zoet en liefelijk (wat is daar mis mee?), maar op een aantal doeken laat De Vries plotseling haar tanden zien. The March of the Geese bijvoorbeeld, toont een stoet ganzen die dreigend op de toeschouwer afkomen, inclusief donkere achtergrond met strepen om de actie te benadrukken. De werken met oesters zijn scherp, hoekig en hebben eenzelfde donkere, actievolle achtergrond. Heerlijk.

En daarna nog een keer naar die donzige suikerspinpleintjes kijken.

Thomas van Huut, NRC

Shows

Free Magazine Subscription

Articles, interviews, shows & events. Delivered to your mailbox weekly.