02 december 2025, Yves Joris

Present Tense: a duo exhibition by Wim Nival and Sam Lock

On a day when the light cannot decide whether to break through or hide behind the clouds a little longer, gallery owner Thijs Dely guides me through the new exhibition Present Tense. He has a certain calmness about him, almost as if he knows I still have to shed the pace of the outside world. “It’s a duo exhibition,” he says, “but one that came together organically.”

He says it in a way that does not minimise, but rather reveals. As if that logic is not the result of planning, but an encounter that presented itself, that simply ‘felt right’. The encounter between Wim Nival and Sam Lock, two artists who had never met before, but who, according to Thijs, from the very first studio visit onward “completely understood each other, even though their practices are different.”

That sentence lingers because I can feel exactly what he means: an under-the-skin agreement that cannot be attributed to style, technique or material, but a shared way of listening. “Thematically, they explore time,” Thijs explains. “How the present relates to the past and the future. That’s where they overlap.” And you sense that he does not mean this theoretically, but as an experience. As in this exhibition, if time is not something you have to understand, but something you are allowed to let seep in.

Wim Nival, Z.T., 2024, Settantotto Art Gallery

With Wim Nival, everything begins with an artistic act of removal. He works with materials that already have—or once had—a life: old book covers, photographs, torn-out pages. But he does not approach them as found objects that need to be saved or preserved, but rather as carriers that must be freed again. “The photo used to be here,” Thijs says, pointing to a sheet from which the image has been completely scraped away. “He scratches the image off entirely, but he is mainly interested in the back.”

That back becomes a new image—a surface that does not yet carry a history of visibility, but one of touch, a sheet that is at once fragile and layered. Nival removes in order to reveal. He cuts, chisels, scratches and takes away, but always with a remarkable tenderness. Never violent. Never intrusive. His interventions have a sense of caring about them, as if he is loosening something to allow it to breathe.

The regularity that appears in his patterns is never mathematical, but rhythmic. Repetition does not become a symbol of control in Nival’s work, but a form of meditative labour. “That regularity of patterns, the repetition of days and time,” says Thijs, “you can associate all sorts of things with it.” And that is precisely its strength: the work leaves opportunity for projection without imposing itself. Not air-tight, but inviting.

The measurable also plays an important role. Nival often uses rulers, measuring sticks, fragments of instruments associated with exactitude. But in his hands, they lose their authority. “We want to measure everything,” Thijs smiles. “But maybe the answer is that we don’t have to measure anything at all.” The ruler becomes not a standard, but a question. What remains when the measurable is released? What if the world does not have to fit into centimetres?

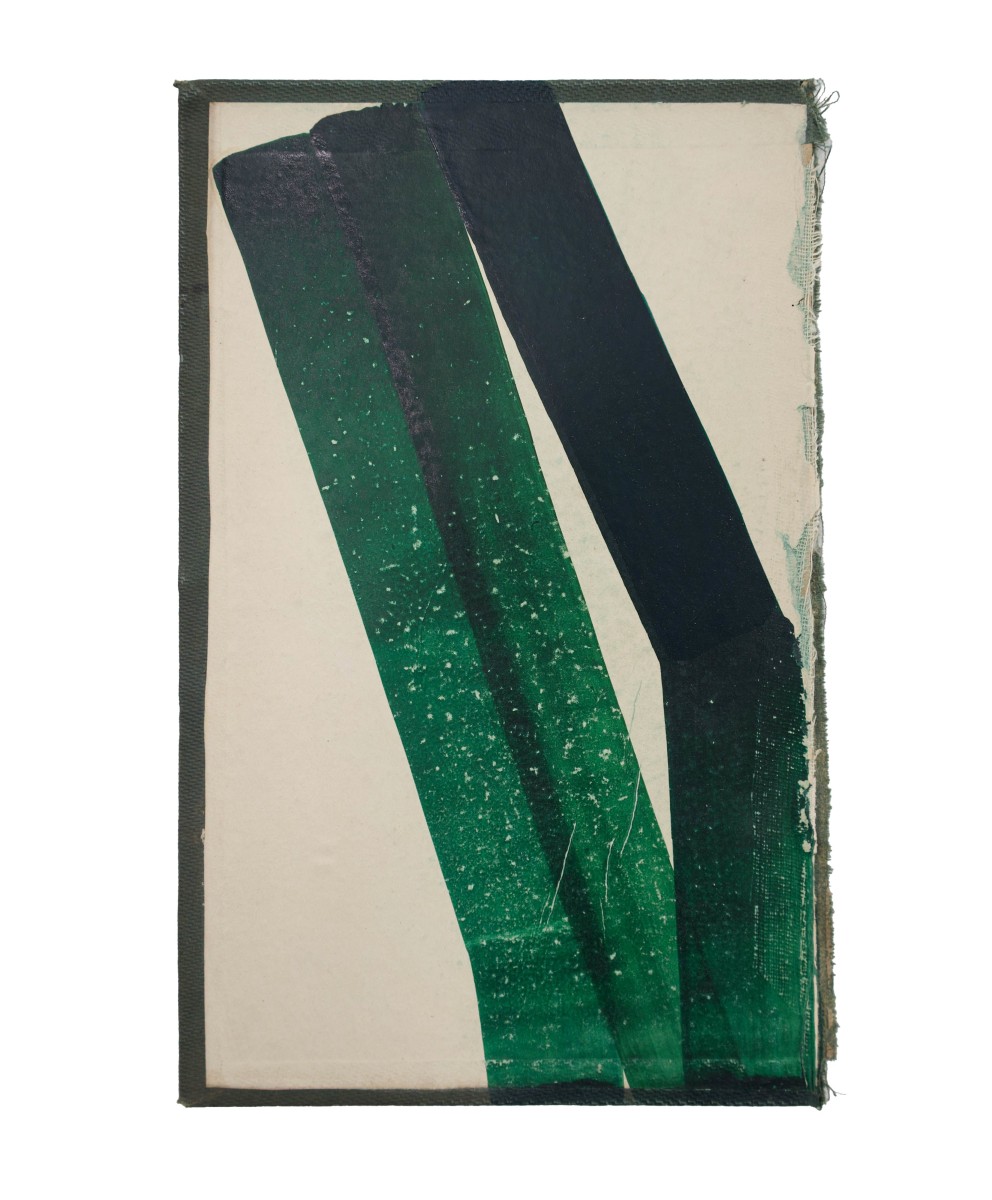

Sam Lock, falling stripes, 2025, Settantotto Art Gallery

With Sam Lock, a very different movement emerges, but with a similar sensitivity. Where Nival removes, Lock allows things to arise—and disappear. He works with inks that are not compatible, mixes water-based with alcohol-based ink and accepts the resistance of his materials as part of the work. “He mixes inks that don’t necessarily adhere,” says Thijs. “He applies marks, but they shift. For him, what remains is that trace. And that’s it.” It is a remarkable kind of trust: he allows the process to play out without trying to control it. This trace—fleeting, unsteady, almost shy—becomes the core of his work.

His supports are also old book covers, cut-out pages, fragments that carry not only text, but also time. He does not use them to quote, but to breathe. A line that dissolves, a stain that lingers, a tone that does not adhere: minute events that translate into a larger story about transience. Lock shows nothing definitive. Everything is in motion, everything is half, everything is in wordless transition.

“It’s not deadly serious either,” Thijs explains. “You can see that it was made with pleasure.” And it’s is true: however fragile or whispering some of the works may be, they convey a sense of playfulness, a kind of quiet freedom without irony.

Present Tense: a duo exhibition by Wim Nival and Sam Lock, Settantotto Art Gallery

Breathing space

In another room, it becomes clear how both artists do not mirror each other, but reinforce one another. Some of Nival’s works are transparently framed, almost floating, as if they refuse to be fully pinned down. Light falls through the cut-outs, shadows forming new patterns that change the work every minute. “When you can really look through it,” says Thijs, “it becomes even clearer: it is the things that are gone that make the work.”

That is exactly what you feel: emptiness is not an absence here, but an active element. What is missing carries the work. What disappears remains present. You not only look at the object, but also through the object, along the object, sometimes even into the object.

Something similar happens with Lock. His play of lines seems to hang in the air. The inks that retreat, the edges that blur, the colours that refuse to stay exactly where you expect them create a kind of slow movement that only becomes visible when you allow your own body to slow down. You notice how his work can hardly be captured in a single glance. It does not ask for analysis, but a kind of immersion.

Thijs explains how neither artist knew the other when the exhibition was planned. He introduced Sam to the space digitally, showed him images, sent work. And when they eventually stood together in Nival’s studio, something happened that Thijs might almost have wished for didactically, but had not dared to predict: “They completely understood each other,” he says, “in so many thematic ways.” Not in terms of form or material, but in terms of attitude towards time.

That attitude makes the space intense, but never heavy. It is an exhibition that does not claim that art must provide answers. Instead, it shows how fragile the answer is. The importance of looking. The necessity of slowing down.

Perhaps that is the intention of Present Tense: no grand revelation, no loud insight, but a shift in the way you look at what you always thought you knew. And perhaps that is exactly what art sometimes needs to be: not a monument, not an explanation, but a thin skin that briefly moves along with your own.

Present Tense: a duo exhibition by Wim Nival and Sam Lock, Settantotto Art Gallery