26 june 2020, Flor Linckens

Lumen Travo - Untitled (Spirit of Changing Times)

Lumen Travo regularly curates a summer exhibition that reflects on social and political elements in our society. Until July 25, you can view the exhibition ‘Untitled (Spirit of Changing Times)’ in the gallery space in Amsterdam. In this exhibition, Atousa Bandeh Ghiasabadi, Judith Westerveld and Thierry Oussou use their work to reflect on these subjects.

Iranian-Dutch artist Atousa Bandeh Ghiasabadi first studied physics and astronomy before venturing into an art academy. “I am a failed astronomer. I thought science was more difficult than art. I was intimidated. But after studying astronomy, I learned that art is more difficult and I have been challenging myself with art and abandoned science.” In her large, poetic and dreamlike drawings and paintings, Ghiasabadi makes connections between Iran and the Netherlands, between war and peace, between man, society and nature. She uses deep, saturated colours and relies on personal memories. The intimate and the political are closely connected in her works and the present and the past regularly seem to overlap. Ghiasabadi grew up in Iran during the Iranian Revolution, in which the dictatorial and pro-Western regime of the Shah was overthrown in favour of (eventually) a dictatorial republic under Ayatollah Khomeini. It was followed by the Iraq-Iran War, often referred to as the First World War of the Middle East. For that reason, Ghiasabadi’s imaginations are often apocalyptic in character, containing both Persian symbols and Western imagery — with occasional references to the work of Frida Kahlo, whose work often moves her to tears. Ghiasabadi also makes films, which have been shown at international film festivals, including IFFR. In her latest series of works, which are on show in this exhibition, the media and the news play an important role. They seem defined by fear, anxiety and danger, but also by powerful and accelerated images that can be a call for action.

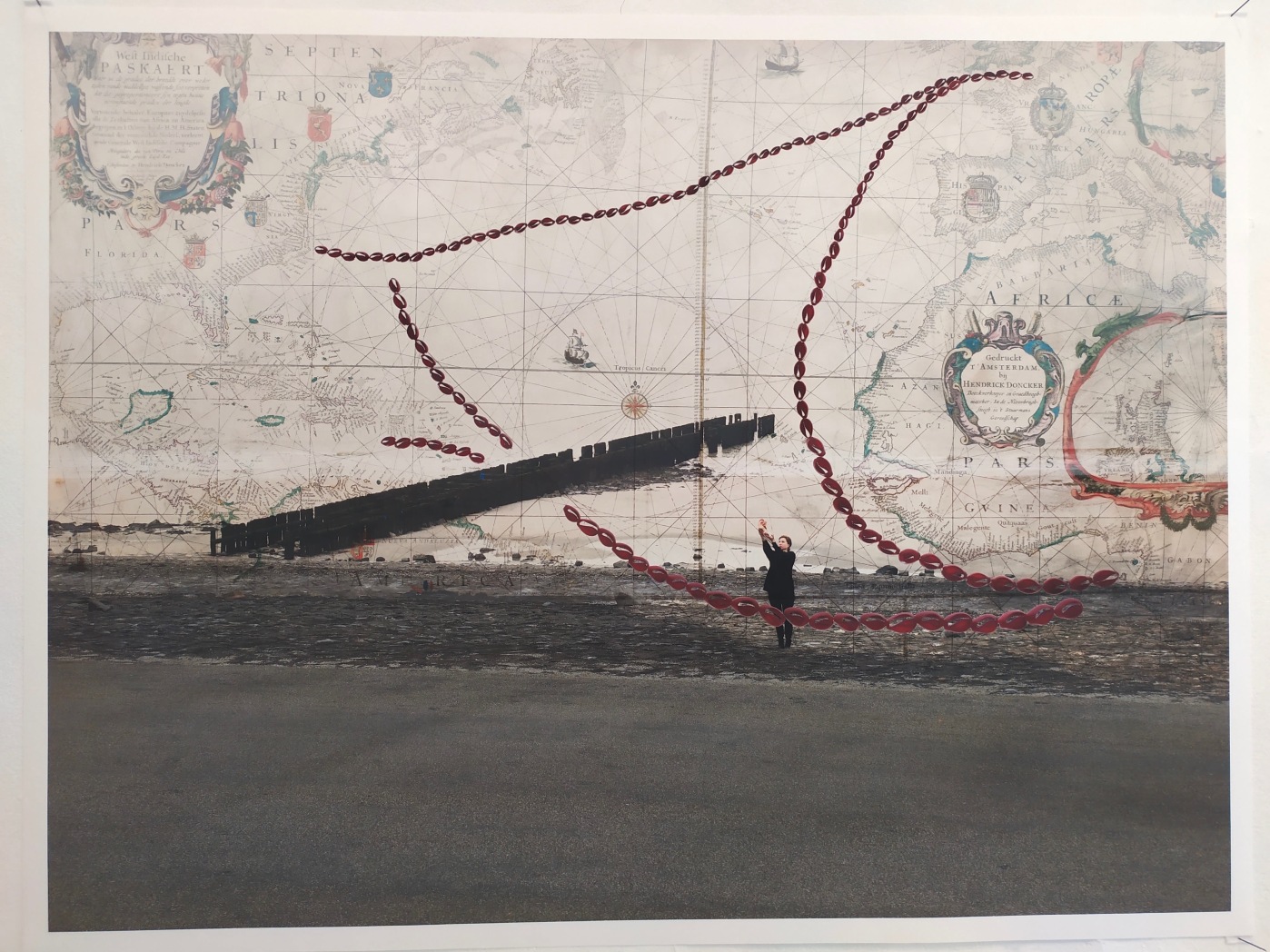

Judith Westerveld was born in the Netherlands but emigrated to South Africa with her parents at the age of eleven. Her work focuses on the postcolonial era in which we live and investigates how the traces of that past are still tangible (and visible) in the present. “Because I grew up in the Netherlands and South Africa, I always feel both an insider and outsider, which might help if you want to address difficult topics. You have very different conversations in South Africa and in the Netherlands. The Dutch colonial past at the Cape is kind of a blind spot here in the Netherlands.” In her work, Westerveld allows for a multitude of perspectives and interpretations and she examines how historical narratives come about. In this exhibition, we see a series of unique works under the name ‘Monetaria Moneta’ (monetary currency). They refer to a specific type of shell that was used as a currency in the transatlantic slave trade in colonial times. This was a lucrative system for traders, because cowrie shells could yield a 500% profit in Africa. These shells were shipped in large quantities to European ports as a stopover before they were used in West Africa to buy enslaved people. For this series, Westerveld explored the (Dutch) Zeeland coastline, where these shells still wash ashore as a result of historical VOC (Dutch East India Company) shipwrecks: as a constant symbol of the important role that the Dutch played in the transatlantic slave trade. In this series, we see how Westerveld performs in this landscape alongside a large ear, that incidentally shows a lot of visual similarities with the shells. The ear symbolises a willingness and openness to listen to these painful histories.

Thierry Oussou describes his artistic method as ‘social archeology’, in which he explores the relationship between ethnographic objects and contemporary art. He actively observes the people around him, their motivations, mutual relationships and interactions. The Amsterdam-based artist was born in the West African country of Benin, that regularly recurs as a subject in his work. For his most recent artworks he researched cotton plantations in Benin and the positive impact of those plantations on the economic growth of the country. The cotton workers and contemporary society in Benin play an important role in this. In his practice, Oussou tries to visualise and record social, historical and political power structures from the past and present before they disappear. “I agree that changes should happen, but I have a desire to document the vanishing before it is completely gone, to keep the trace of the tradition, the imprint of the past in the future. Forgetting and not being aware of your own history can also be used as a tool of manipulation by politicians, thus I also feel there is a need to save some things just for the sake of knowing.” The board game Adji, one of the oldest and most popular games in Africa, also plays an important role in Oussou's work, as a metaphor for a society with certain inherent rules. In the exhibition in Lumen Travo, Oussou presents a selection of new works on paper, using ink, acrylic, oil bars and charcoal from the plantations. He prefers paper over canvas because it is less rigid and has a modest character. “Paper, like the human being, is fragile. This highly symbolic medium is with us our whole lives, from the birth certificate to the death certificate.” It is also a material that can be easily torn, burned and layered. That way, the traces of his artistic process generally remain visible. Oussou's work is currently also on display in the Oude Kerk as part of Unlocked-Reconnected.