28 september 2023, Wouter van den Eijkel

Good Machine, Bad Machine - Meiro Koizumi

In his sixth solo exhibition at Annet Gelink Gallery, Japanese artist Meiro Koizumi connects hypnosis with technology and nationalism, three things that at first glance do not seem to have much in common, but blend into one under Koizumi's direction.

The title of the installation refers to Bruce Nauman's video work Good Boy Bad Boy (1985) in which two actors pronounce variations on the sentences I am good boy and I am a bad boy while going through the emotional spectrum. In doing so, Nauman questions the veracity of emotions and speech.

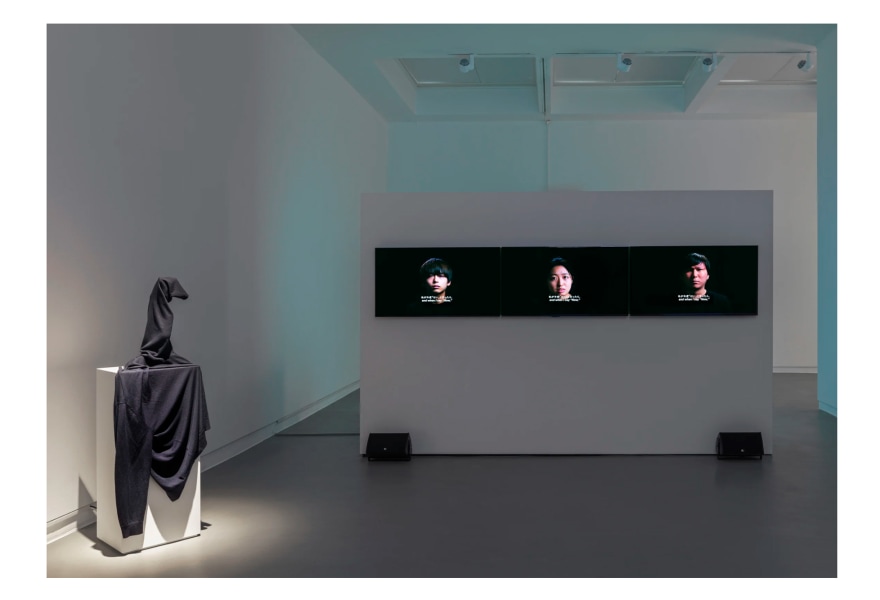

Koizumi's video installation is situated in the middle of the gallery and covers almost the entire width of the space. The front consists of three monitors on which two or three actors can be seen simultaneously. To the left is a robot sculpture, while the back of the installation consists of a large screen showing a collage of nationalist demonstrations.

Like Nauman, Koizumi's actors also go from calm and shy to exuberant, frustrated and angry. The difference with Nauman's installation is that Koizumi's actors are hypnotised. They say short sentences like "forgive me", "escape", and "I am a good person". Sometimes, you can hear the hypnotist's instructions: “This is frustrating”, “You're getting really angry now” or “You don't know exactly why, but this feels really good.”

Meiro Koizumi, The Symbol #12, 2023, Annet Gelink Gallery. Photo: G.J. van Roil

The hypnotist not only gives instructions, but also indirectly asks the questions that Koizumi raises, albeit as an imperative. What exactly is free will if you are told what to feel? Translated to today’s society, the question is: what do you actually feel and think and what are you made to believe by media and technology that constantly surrounds us? Good Machine Bad Machine is as much about our trust in authority as it is about the power relationship between hypnotist and hypnotised person: master and slave.

At other times, Koizumi has cut out the hypnotist's voice, making it seem as if the emotions are autonomous. Yet, no matter how high the emotions run, the endless repetition of the gives them an empty and mechanical feel. The thin dividing line between man and machine/technology is emphasised by the robot arm donned in a sweater to the left of the installation. The arm moves to the rhythm of the actors' statements.

Nationalism as a state of hypnosis

Meiro Koizumi lives and works in Yokohama, but was a resident at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam in 2005 and 2006. When he returned to Japan, he was able to see his homeland with a fresh pair of eyes. “When I went back home, I noticed that the mood in Japan had changed. Our economy had stagnated and the population had begun to shrink, while China had become a world power, South Korea was thriving and North Korea was at our doorstep. Japanese self-confidence seemed to have taken a hit.”

This provided fertile soil for populist rhetoric embracing a glorious past and appealing to nationalist sentiment – something that is even more controversial and sensitive in Japan given its recent colonial and imperial past than, for example, in Belgium or the Netherlands.

Meiro Koizumi, We Mourn The Dead Of The Future, 2019, Annet Gelink Gallery. Photo: G.J. van Roil

As an indication of how delicate nationalism and military display are in Japan, a corollary of that past is that Japan has had no army since the World War II, only a small number of self-defence forces. This also means that the country has no conscription and the question of whether they would be willing to die for the homeland has not been asked of young people for more than 75 years. Now that the geopolitical situation is shifting, that question is suddenly very much relevant once more. In another recent multi-channel video installation, We Mourn the Dead of the Future, shown in 2019 at the Annet Gelink Gallery, Koizumi poses this exact same question to a group of young Japanese.

Good Machine, Bad Machine

Back to Good Machine, Bad Machine. After the seaquake near Sendai in 2011, which we mostly know about because of the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant, Japanese nationalism took the form of gatherings and demonstrations involving national symbols, symbols that are resistant to natural disasters, which you can fall back on when the world around you literally and figuratively collapses.

Koizumi filmed them for 11 years: from salutes on the occasion of the emperor's birthday to demonstrations against the increasing influence of Korean culture and around the 2020 Olympic Games. Sometimes, Koizumi stood in the crowd and filmed up close, showing what seemed to be ordinary citizens, mostly men, often older and often carrying a Japanese flag. He alternates with shots from far away. Through a bush, we see soldiers firing a cannon or a column of buses with demonstrators approaching on a highway.

Meiro Koizumi, Good Machine Bad Machine, Annet Gelink Gallery. Photo: G.J. van Roil

The result is a collage-like report with its own rhythm, which draws you into the film. Koizumi has also noted this similarity with hypnosis, which is partly why he decided to take a closer look at the phenomenon. He added the soundtrack from the front to his recordings.

Since the two films are not the same length, each viewing experience is unique, but the effect is always the same: nationalism is equated with a state of hypnosis, a state in which emotions seem to run wild and are safely projected towards a glorious future or mythical past, but in which the balance of power always remains the same.

The question that Koizumi rightly poses is: are we the masters of our emotions and do we consciously choose to get excited about certain things, or are we fuelled by technology and are we unconsciously guided by propaganda? A rhetorical question according to Koizumi because “After all, we are always surrounded by language and messages because that's how our brain works.”

Good Machine Bad Machine by Meiro Koizumi can be seen at Galerie Annet Gelink in Amsterdam until October 28

Meiro Koizumi, Good Machine Bad Machine, Annet Gelink Gallery. Photo: G.J. van Roil