24 march 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

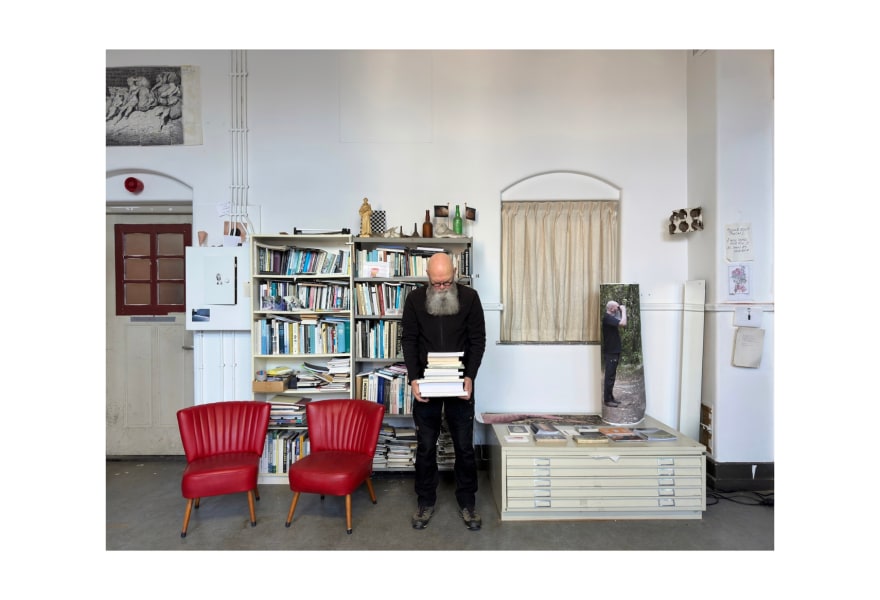

The studio of... Frans van Lent

If you have two studios in two countries, do you create different work in each? We asked Frans van Lent. He works in both Dordrecht and Hautefort in the Dordogne region. The differences are significant. The work he creates in the Netherlands is more conceptual. The score, the instructions for a performance, can be worked out in detail beforehand. Afterwards, he rarely needs to make adjustments. In France, on the other hand, he works more intuitively and sometimes even surprises himself with the outcome.

This summer, Van Lent is organising the third Nieuwstraat Festival, a performance festival on the street in Dordrecht where he lives. On a Saturday in June or July, volunteers will be performing based on scores from international artists. The exact date of the festival is not announced in advance, so that the performers can carry out their work in an anonymous and safe environment.

Van Lent is still looking for volunteer performers. Asked about the ideal profile of a volunteer, he responds, “Volunteers should be interested in the theme of the inconspicuous. The festival should primarily be a personal experiment for them.”

You live and work in Dordrecht and Hautefort, France. Do you have a studio in both places and what do they look like?

Yes, I have a studio in both, but they are very different. In Dordrecht, I work in a classroom in an old primary school. The building has been converted into a studio complex where ten artists work. Here, I focus mainly on connecting my work with others, organising activities in and outside my studio and setting up small-scale festivals.

In Hautefort, I work in a space in my home, but I actually consider the rural surroundings of my house to be my actual studio. I walk a lot and my work emerges from constant interaction with the environment. There, I am more focused on reflection and solitude.

What makes a good workspace for you?

To me, only one thing really matters: the workspace should inspire me to create. It can be indoors, with my books and computer within easy reach, but preferably outdoors in silence, with or without a camera.

Do you notice that you create different work in France than in the Netherlands,?

Since both places are so different, the entire work process is also completely different, resulting in fundamentally different work.

Frans van Lent, Staan (Tenerife 2010).

What do you mean by that?

The work differs in both intent and feeling. What I create in the Netherlands is often more conceptual. This work is usually fully thought out in detail before execution and only needs to be carried out. For example, the piece "A Day" (2024).

What I create in France often revolves around my physical presence in the landscape. This work is more intuitive. The process is generally more open-ended and I am often surprised by the outcome, such as in "Right and left" (2025).

For the first category, I can write the textual description almost definitively beforehand, while for the second, the description usually changes a lot afterward. But these aren’t strict rules—there are many nuances in between.

Your gallery, Studio Seine, describes your practice as a ‘concept-driven research process guided by personal experience’. That sounds quite abstract—can you give an example?

The following work was conceived and carried out as a performance. The description of the process is, on completion, the only thing that remains:

Short-term memory (2019)

This morning we drove out to the fields.

We stepped out of the car and started to walk.

My camera was charged, and in it was an empty memory card.

I took photos of the scenery we walked through.

We walked for about an hour, then we sat down.

After a few minutes we walked back on the same route.

At every spot where I had earlier taken a photo,

I now deleted that specific photo.

When we arrived at the car park, the card was empty again.

We got in the car and drove away.

With this kind of work, I want the concept to be read as a suggestion from me, a possibility for the reader to carry out personally. That personal experience is my goal, both my own experience and that of my ‘audience’.

A text-based work like the one above often remains without images. I think an image defines the event as something that the other (the artist) has experienced, making the reader an outsider. I prefer that the reader feels involved, seeing the performance as a potential personal experience: ‘If I wanted to, I could do this myself.’

In 2016, I founded TheConceptBank.org, a website where donated scores (descriptions) from 60 artists are available. Visitors can print them free of charge and perform them whenever and wherever they want—in other words, transforming an artist’s concept into their own experience.

Me in a place I've never been before.

Frans van Lent, Places, 2023, Studio Seine

Much of your work falls under performance art. In a material sense, little remains of your work besides a manual or pictures of the performance. Isn't it difficult to build an oeuvre this way?

The performances usually take place without an audience, so afterward, a text is often the only record. These texts sometimes resemble poetry; I strive for the most concise and unambiguous form. Poetry often emerges in the reader’s reflections. I think it’s fantastic if my work leads to a new thought or insight.

I consider the publications on my website to be a continuously growing catalogue of my oeuvre. In general, I consider publishing on the site as the finalisation of the work. But not all my work exists solely as text — depending on the nature of the work, I also use photography, video or audio. I have no fixed rules.

In June or July, the third Nieuwstraat Festival will be taking place. What is it and why did you start it?

The Nieuwstraat is the street where I live—a regular street in the centre of Dordrecht. On an unannounced Saturday in June or July 2025, between sunrise and midnight, the third Nieuwstraat Festival will be taking place. On this day, volunteers — often inconspicuous — will perform based on instructions or ‘scores’ from international artists.

Passersby will observe the work, but apart from a clear artistic context, they may not recognise this as art or performances. In other words, the unusual is hidden in the ordinary.

Why is it important that the date is not announced in advance?

This kind of festival is not aimed at an audience of spectators. It is primarily about the experiences of the performers themselves—they essentially become their own audience. The actions they perform have no special meaning for passersby because there is no explicit artistic context.

The volunteers perform in (for them) safe anonymity. This is why the date is not communicated beforehand. A gathered audience would undermine the entire anonymous concept. This festival is part of a long series, starting with the Unnoticed Art Festival, which I organised in Haarlem in 2014. A book about the festival, titled Unnoticed Art, was published by Jap Sam Books.

Me in a place I know very well.

Frans van Lent, Places, 2023, Studio Seine

The Nieuwstraat Festival relies on volunteers. Would you like to make a call for volunteers? And what should they be able to do?

Volunteers should be interested in the theme of the inconspicuous. The festival should primarily be a personal experiment for them. At the same time, it involves collaboration with a group of strangers, yet like-minded people. There is also the intriguing sense of sharing a secret. If you would like to be part of it, send an email with a short explanation of why you want to participate to mailto:[email protected]. Keep in mind that this is a no-budget project.

What are you currently working on?

At the moment, I am organising the Equinox performance manifestation on 23 March in Dordrecht, where 20 performers will be improvising together to celebrate the biannual equinox. From mid-April, I will be spending two months in residence at Foundation OBRAS near Évora, Portugal. It will be two months of silence in a landscape of cork oaks and marble quarries. In my mind, I am already halfway there.