21 october 2024, Yves Joris

Windows to words, thinking and writing at Coppejans Gallery

At Stijn Coppejans’ gallery, located in Antwerp’s gritty Red Light District, an exhibition has been put together that goes beyond the visual. As the title suggests, thinking-writing is an exhibition that not only explores writing, but also the thinking that precedes it, and sometimes also follows it. With playful reference to today’s tendency to quickly jot things down — often only thoughtfully considered afterwards — this exhibition invites reflection and perhaps even some self-reflection.

At the heart of the exhibition is work by Alain Arias-Misson, a Brussels-based artist who has gained worldwide recognition for his public poems. But his work is more than just text; it is poetry in space, shaped within public spaces. These ‘public poems’ create an intriguing dialogue between language, architecture and accidental passersby. Arias-Misson began a revolutionary concept in the late 1960s, when he asked actors to carry letters through the streets and form words in squares and intersections, visible only temporarily before reverting back to the everyday street scene. This was poetry that lived and moved, poetry that was experienced.

It is precisely this dynamic of words and thinking, of form and content, that characterises Coppejans’ exhibition. As you wander through the space, you are confronted with work that raises as many questions as it answers. What does it mean to write? And what does it mean to think before you write? These questions are asked repeatedly, not only by the historical work of Arias-Misson and contemporary Paul de Vree, but also by younger voices like Maarten Ingels, all of whom engage in a visual and poetic dialogue in their own unique way.

Alain Arias-Misson, Juggling with poetry, 2024, COPPEJANS GALLERY

Writing as action

Alain Arias-Misson's public poems raise questions not only about language, but also action. The letters that appear in the streets create a temporary disturbance, a fleeting interference in everyday life. During the Franco regime, for example, he formed the word ‘Dada’ in front of Franco’s headquarters — a bold act that was immediately suppressed by the police. But as the artist demonstrated, even silence is a form of communication. When he was no longer allowed to use words, he began working with symbols — question marks, quotation marks, ellipses — that could speak as much as words.

In thinking-writing, this idea is developed further. In one work, Arias-Misson subtly rotates the letters of a poem, altering its meaning. A small shift in the order of letters and words can produce an entirely new interpretation. In doing so, space is created for the viewer to reflect, to think about what we say and how we say it.

The exhibition also raises questions about the role of art in an increasingly fleeting society. Whereas poetry was once carefully composed and printed, today’s quick social media posts often influence our thinking. With his public poems, Arias-Misson offers an alternative: poetry that forces you to stop and reflect, creating a moment of contemplation in a world in constant motion.

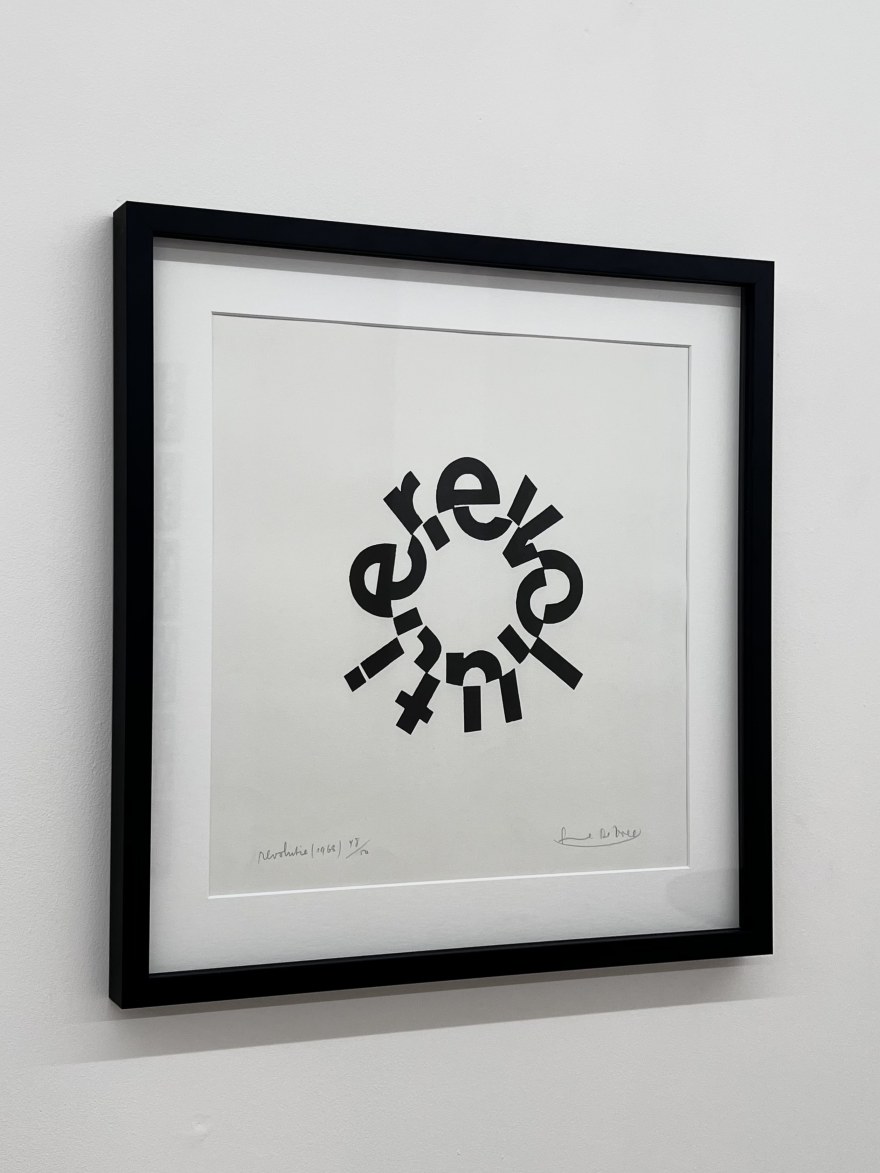

Paul De Vree, Revolutie, 1968, COPPEJANS GALLERY

Paul de Vree’s secret Antwerp

Although Arias-Misson plays a key role in the exhibition, he is not the only poet in the spotlight. Paul de Vree, one of the pioneers of concrete and visual poetry, is also represented. His work, often expressed in minimal textual forms, pushes the boundaries of poetry. His most famous work, Revolution, is limited to that one word, written in a circle. With just one simple shift — the rotation of the inner circle — he gives the word a new dimension. It evokes images of upheaval, both literally and figuratively.

What makes this exhibition so unique is that De Vree’s work has not been shown in a gallery context for many years. Thanks to Coppejans, De Vree’s work is now available again, being exhibited for the first time in a long while. This work, like that of Arias-Misson, may seem simple at first glance, but on closer inspection, reveals a deeper layer. De Vree’s poetry is both visual and linguistic, challenging the viewer’s expectations.

Maarten Inghels, Choose your fighter, 2024, COPPEJANS GALLERY

In addition to the historical work, thinking-writing also offers an opportunity for younger artists inspired by the legacy of Arias-Misson and De Vree. For example, Maarten Ingels transforms his own books into new visual objects. In a previous project, he altered his unsold books with pellets, but now he presents his own visual poems. His work Ventje Zot, a neon sign shaped like a little man with the word zot (‘lunatic’), brings a smile to everyone who passes by. This simple image touches on something fundamental in Flemish culture and shows how words and images can melt together to become poetry.

Ingels’ work aligns seamlessly with the theme of the exhibition: the relationship between words, thinking and the world around us. His works in neon, bright and brilliant, draw the attention of passersby in the Red Light District. But like the works of Arias-Misson and De Vree, there is more to them than meets the eye. These works demand reflection, a pause in our daily lives to think about the words we use and how we shape them.

Maarten Inghels, ZOT, 2023, COPPEJANS GALLERY

In many ways, thinking-writing serves as a window to the depth of language and meaning. As Coppejans himself says, the works on display here are ‘windows to more’. Each work, however simple, offers a glimpse into a broader world of thoughts and ideas. And although the first impression matters, this exhibition invites you to linger, to think more deeply.

The exhibition shows that visual poetry is more than a niche art form; it is a way of viewing the world, of rethinking and reformulating words. In an age where we write and think far too quickly, thinking-writing offers a welcome respite, a moment of rest and reflection. It is an ode to the power of words, but also to the thinking that precedes — and sometimes follows — them.

With thinking-writing, Coppejans not only shows us a treasure trove of Antwerp poetry, but also the enduring relevance of language in our visually dominated world.

Thinking - Writing, COPPEJANS GALLERY