Until the mid-1990s, Van Empel created his photographic assemblages using traditional collaging techniques of cutting pasting and retouching. In 1995 Van Empel switched to a digital process, using a computer to create his conceptual photographs. Using a vast stock of digital photo’s to create his photographs, Van Empel changed the face of digital fine-art photography. On the basis of this art-historical reference, Van Empel created a new genre within photography – without a ready-to-wear label. The artist himself speaks of the ‘construction of a photographic image, or photo objects’. Although he does make use of pure photomontage – he never applies so-called morphing techniques – in his final image he strives for a naturalism and realism as opposed to a surrealist approach. The artificiality is visible but the final image is a convincing, autonomous reality. Although produced digitally, Van Empel’s images are unique, each being built up of different combinations of photo’s. He uses photography as an independent form of depiction. Though digitally produced, the camera and photography remain at the heart of his practice. Every image consists of photographs taken by himself, which are then digitally assembled on the computer. The camera provides the building blocks of his compositions. Van Empel’s works are constructed down to the minutest of details, in which he considers the exact placement of every element, giving his images a sense of idealized perfection. Though created in the digital age using the most up-to-date techniques, Van Empel’s work defies temporal structures and instead represent universal themes.

Text by Alex de Vries

Text by Alex de Vries

Artworks

Articles

Media

Highlights

Recommendations

Collections

Shows

Market position

CV

Articles on Ruud van Empel

Media

Hollandse Meesters: Ruud van Empel

Shows

Market position

RUUD VAN EMPEL SEISMOLOGIST OF AN IMAGE AGE

We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars, now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.

Cooper, Interstellar

Do you recognize the feeling? Out of panic and survival instinct, a group of people start walking in a certain direction. You hesitate, wait and seem crazy when you are the only one who remains still. You make an opposing decision and abandon the herd behavior…. The outcome is highly uncertain, but at least you make an informed choice.

In a time where the herd literally answers all emotions with a thumbs up and digitizes a one-sided catalog of feelings in an average of 280 characters via social media, I consider Ruud van Empel to be such a “madman. He remains standing, looks around attentively and realizes that he is part of a visual culture that can best be described over the last thirty years as a tangle of ideas and ideologies that become visible mainly at a crossroads of financial capital and (visual) information technology. In other words, our capitalist society has ensured in an inimitable way that we are more formatted in our thinking and actions than ever before and we present ourselves to the world in a quasi-identical way.

That visual culture plays an important role in today’s formatted and homogenized social narratives is obvious. The Techboys, who reward herd behavior as purebred popularizers, have embraced data-driven visual culture as an ideal ally from the outset Everyone is sensitive to images, after all. As a result, more than ever, visual culture is also understood in economic terms and handled as “visual capital,” and that visual capital, by stubbornly defining what is “own” and what is “foreign,” continually sets the social debate on edge.

Perhaps this is an inevitable consequence of digitization in the mid-1990s and the accompanying identity crisis of the medium of photography. The “truthful” analog photography was exchanged for a digital question mark without too much pretension to truth. In other words, the emergence of digital photography immediately neatly sanitized and retouched the soil of the Big Truths, to the extent that roughly thirty years later illustrated fake news has become indispensable to public debate. This kind of formatted, usually staged polarization – fake versus real – plays out in many areas of society (politics, ecology, culture, economics…) and over the last few decades has become a convincing business model with profiteering potential. In short, “image capitalism. A capitalism driven by algorithms that gradually makes our consumption of images indigestible. It is this ‘image capitalism’ that now feeds daily on a digital toolbox; an inexhaustible source of seemingly visually infallible, but above all ruthless social perspectives. Everything is possible. But what is really possible today?

Such visual upheavals not only form the background to van Empel’s entire career, it is also the hybrid raw material for his graphic, optical, perceptual, mental and verbal images. A vast visual habitat with which van Empel likes to rearrange our relationship to the image. Van Empel directs that habitat with a tight hand and, like one of his points of reference, filmmaker Roman Polański, possesses the visual acumen to make both the cultivated and the brutal speak in detail. Before I expand on that, however, it is appropriate, with respect to our viewing of Van Empel’s work, to clear up some misunderstandings.

Botox exoticism

Indeed, a viewer looking at Ruud van Empel’s work with a cursory glance is often tempted to consider the technicality of the images as an exotic, almost surreal variant of the cultural homogenization described earlier. Yet here I want to put an immediate end to this kind of botox exoticism. For it crops up all too often in reactions surrounding Van Empel’s work in which technical elaboration comes to dominate the final judgment of the work.

The way in which these images have been technically created since the mid-1990s obviously forms an important foundation in van Empel’s oeuvre. The work develops during the late 1980s from an analogous thinking and acting (the pure photomontage) into what van Empel describes today as a “technical naturalism” or even “a form of realism. In any case, far away from what that unsuspecting observer rather appoints as an exotic, surrealistic approach. These are statements that obviously based on the ingenious digital thinking that van Empel employs, but surrealism, no, it is not. Van Empel is not a seasoned surrealist who pursues the unreal. On the contrary. Rational thinking remains a core concept in all of Ruud van Empel’s series in which, in contrast to surrealism, visual and textual imagination are never detached from reason and logic. So no surrealistic fabrications that have been created with the aid of, for example, digital morphing techniques. But an ‘autonomous reality’ as van Empel prefers to define it. Digitally produced, but first photographed with the camera within often self-designed, tangible (studio) settings. It forms the core of an artist’s practice in which the visual material created by van Empel is then digitally assembled down to the smallest details. And even though they refer to each other in van Empel’s work, the analog and the digital also function here perfectly alongside and without any knowledge of each other.

Perfectionism is an imaginary, philosophical concept

That this results in what many critics describe as a “beautiful,” “dreamy,” “sweet universe” with a number of “images perfected to the ultimate level” is not only a second misunderstanding but also a deliberate trap. We may never see or hear van Empel from the barricades, any form of activism is alien to him, but the insight that an image is never neutral and transcends the perceptible is always a masterstroke in van Empel’s work. Thus Van Empel rightly considers perfectionism as a imaginary, philosophical concept and not necessarily a merely simplistic, observable one. Striving for perfection is human, undoubtedly seductive and socially more topical and popular than ever. But the result today is plainly baffling. An observation that does not escape van Empel either.

Since perfectionism has become the social measure of things – the landscape, the living room, the partner… preferably all as perfect as possible – and in the process uses visual culture as a grateful and cheap accelerant, we also fall into the trap more than ever. A lot of people, not least strongly driven by a ruthless image culture that goes wild via social media, still do not understand why the perfect life does not exist and is unrealistic. Indeed, the perfect life is imaginary, elusive, unrealistic, let alone desirable. A realization that is barely gaining ground socially because the prevailing visual culture is eager to convince us otherwise.

When a goal is unrealistic – which perfection is – it even becomes potentially dangerous: “In an attempt to take a perfect selfie at a waterfall, five young women fell off a cliff in India. This recent and certainly not the last incident in the addictive search for perfection, in casu the perfect image, also indirectly illustrates the way we often look at Ruud van Empel’s “perfect” work. We are attracted by an idea of perfection but few see the real challenge. Indeed, the ‘technical perfection’ so much talked about in van Empel’s work is not a goal, but a deliberate means. An invitation, following the imaginary, philosophical concept of “perfection,” to look at other philosophical themes within Van Empel’s work in a way that transcends notions of technicality, analog or digital mastery.

Defiant imagination

So, what type of sculptor is up to this? What are we actually looking at when we behold Ruud Van Empel’s “perfect” images? The answer is as simple as it is complex: contrary imagination wrapped in stylistic, visually appealing concepts and ideas. For more than technique, genre or any other categorization we rather too often steal from the Great Register of Art History to say something about a photograph, this photographic work is a philosophical history of themes.

Van Empel turns temporal structures and universal themes inside out and proves how we can make images today from a much-needed trans literacy. Trans literacy understood as an artist’s position, as a conscious choice to adopt a literate and intellectual position within the prevailing visual culture. With and in images. But, as van Empel immediately adds, it is not only the making of these kinds of images that is important today, but also how we as viewers can look at images more critically and, above all, why we should look at images more attentively. In the way in which through this oeuvre, for example, the strongly evolving asymmetry can be deciphered in the relationship between those who look and others who are looked at, it seems as if van Empel has been challenging the ubiquitous visual gaze on its merits for almost four decades now.

All of these image series embody this asymmetry. Photo Sketch (1995- 2003), The Office (1995-1998, 2001), Study for Women – The Naarden Studies (1999-2000) or more recently Souvenir, Souvenir d’intime (2008, 2015) are issues that give van Empel’s oeuvre that special, philosophical temperament.

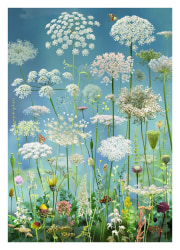

Complemented by van Empel’s views on themes that have been subject to seismic shifts in recent decades that are surfacing all over the world and, consequently, in the inseparable visual culture. We see those shifts in image series when van Empel clearly reflects on notions of cultural appropriation (Still Life, 2014-2015, 2017) or perfection versus imperfection (Theatre, 2010-2013). But also about nature as an undeniably political fact (Voyage Pittoresque, 2016-2019 and Floresta, Floresta Negra, 2018), a digital world that more than ever eludes the analog world (Unititled, Study in Green, 2003-2004), the artist who archives to forget (Generation, Wonder, Club, 2010-2011), molding the notion of beauty into a disturbing yet effective visual attack strategy in the face of narrow-minded notions (Collage, 2017) or abstract landscapes (Pollution, 2022) in which absolute freedom of expression manifests itself as a unique, slightly rebellious signature. They are reflections all contained in this body of work. Those who look back on this time, say fifty years from now, may find in van Empel a man of honor who perfectly captures the moral epoch in his oeuvre.

Moral rearmament

Ruud van Empel takes a challenging approach in every series. Never non-committal, but extremely thoughtful and usually on the basis of a playing field that repeatedly confronts you with a number of confrontational facts forces you to face a number of facts. In recent years, for example, World (2005-2008, 2010, 2017) received a lot of attention. Within the Christian tradition, the white child is a form of standard iconography to represent innocence. From the idea that black children are just as innocent as white children, Van Empel has visually redefined the concept regarding guilt and innocence.

World, which deals with black innocence, was already an unmistakable statement in 2005 that has lost nothing of its topicality to this day. On the contrary. In the wake of the worldwide events surrounding the death of George Floyd in 2020, that same black skin has become a political statement for many viewers. To many, what van Empel does in World is a form of gratuitous cynicism, but nothing could be further from the truth. Cynicism is a wry joke that dare not face the truth. Van Empel thinks differently. He is more human, more engaged and more sincere. He is, including with a statement like World, ahead of his time. Far away from any kind of cynicism. It brings me to a stimulating slogan: ‘The visual language of Ruud van Empel offers the moral rearmament that our visual culture needs’! Free of pomposity, populism and leaden moralism, but with a finely tuned sight towards people and their environment. A view that with Van Empel is characterized by reason and compassion and consciously reveals itself as a necessary plea for a new humanism. A humanism that recognizes the facts; we are improving overall, but at the same time also a humanism that fully realizes that we as humanity are firmly under pressure. Not least because of the prevailing skepticism and broad-based demagoguery that undermines confidence in scientific, inclusive and, above all, reasonable thinking. In Ruud van Empel’s work, it produces a form of magical thinking, a thinking around what is possible. For if we wish to continue to describe visual culture effectively as an expression of human expression, as well as communication between people, then Ruud van Empel’s oeuvre is an offer you can’t refuse.

In a quasi-uniform visual culture where everything is customized and personalized, Ruud van Empel’s work presents a beautiful paradox. Like a seismologist who scientifically records the vibrations in our visual culture and at the same time fully realizes that what you see depends not only on the context, your knowledge, your personality or your cultural baggage, but especially on the unpredictable moment. That’s where you make the difference as an artist. The moment when you decide to walk with the herd. Or not. And the latter has been a deliberate and masterful choice for van Empel for decades. Call it Van Empel’s avant-garde, a positively colored philosophy of life and an oeuvre that can be described as the necessary “experimental vanguard. Only in this way can Ruud van Empel carefully portray an image of the era. And meticulousness is far from perfection.

Christoph Ruys, former director of the Photography Museum Antwerpen FoMU

We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars, now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.

Cooper, Interstellar

Do you recognize the feeling? Out of panic and survival instinct, a group of people start walking in a certain direction. You hesitate, wait and seem crazy when you are the only one who remains still. You make an opposing decision and abandon the herd behavior…. The outcome is highly uncertain, but at least you make an informed choice.

In a time where the herd literally answers all emotions with a thumbs up and digitizes a one-sided catalog of feelings in an average of 280 characters via social media, I consider Ruud van Empel to be such a “madman. He remains standing, looks around attentively and realizes that he is part of a visual culture that can best be described over the last thirty years as a tangle of ideas and ideologies that become visible mainly at a crossroads of financial capital and (visual) information technology. In other words, our capitalist society has ensured in an inimitable way that we are more formatted in our thinking and actions than ever before and we present ourselves to the world in a quasi-identical way.

That visual culture plays an important role in today’s formatted and homogenized social narratives is obvious. The Techboys, who reward herd behavior as purebred popularizers, have embraced data-driven visual culture as an ideal ally from the outset Everyone is sensitive to images, after all. As a result, more than ever, visual culture is also understood in economic terms and handled as “visual capital,” and that visual capital, by stubbornly defining what is “own” and what is “foreign,” continually sets the social debate on edge.

Perhaps this is an inevitable consequence of digitization in the mid-1990s and the accompanying identity crisis of the medium of photography. The “truthful” analog photography was exchanged for a digital question mark without too much pretension to truth. In other words, the emergence of digital photography immediately neatly sanitized and retouched the soil of the Big Truths, to the extent that roughly thirty years later illustrated fake news has become indispensable to public debate. This kind of formatted, usually staged polarization – fake versus real – plays out in many areas of society (politics, ecology, culture, economics…) and over the last few decades has become a convincing business model with profiteering potential. In short, “image capitalism. A capitalism driven by algorithms that gradually makes our consumption of images indigestible. It is this ‘image capitalism’ that now feeds daily on a digital toolbox; an inexhaustible source of seemingly visually infallible, but above all ruthless social perspectives. Everything is possible. But what is really possible today?

Such visual upheavals not only form the background to van Empel’s entire career, it is also the hybrid raw material for his graphic, optical, perceptual, mental and verbal images. A vast visual habitat with which van Empel likes to rearrange our relationship to the image. Van Empel directs that habitat with a tight hand and, like one of his points of reference, filmmaker Roman Polański, possesses the visual acumen to make both the cultivated and the brutal speak in detail. Before I expand on that, however, it is appropriate, with respect to our viewing of Van Empel’s work, to clear up some misunderstandings.

Botox exoticism

Indeed, a viewer looking at Ruud van Empel’s work with a cursory glance is often tempted to consider the technicality of the images as an exotic, almost surreal variant of the cultural homogenization described earlier. Yet here I want to put an immediate end to this kind of botox exoticism. For it crops up all too often in reactions surrounding Van Empel’s work in which technical elaboration comes to dominate the final judgment of the work.

The way in which these images have been technically created since the mid-1990s obviously forms an important foundation in van Empel’s oeuvre. The work develops during the late 1980s from an analogous thinking and acting (the pure photomontage) into what van Empel describes today as a “technical naturalism” or even “a form of realism. In any case, far away from what that unsuspecting observer rather appoints as an exotic, surrealistic approach. These are statements that obviously based on the ingenious digital thinking that van Empel employs, but surrealism, no, it is not. Van Empel is not a seasoned surrealist who pursues the unreal. On the contrary. Rational thinking remains a core concept in all of Ruud van Empel’s series in which, in contrast to surrealism, visual and textual imagination are never detached from reason and logic. So no surrealistic fabrications that have been created with the aid of, for example, digital morphing techniques. But an ‘autonomous reality’ as van Empel prefers to define it. Digitally produced, but first photographed with the camera within often self-designed, tangible (studio) settings. It forms the core of an artist’s practice in which the visual material created by van Empel is then digitally assembled down to the smallest details. And even though they refer to each other in van Empel’s work, the analog and the digital also function here perfectly alongside and without any knowledge of each other.

Perfectionism is an imaginary, philosophical concept

That this results in what many critics describe as a “beautiful,” “dreamy,” “sweet universe” with a number of “images perfected to the ultimate level” is not only a second misunderstanding but also a deliberate trap. We may never see or hear van Empel from the barricades, any form of activism is alien to him, but the insight that an image is never neutral and transcends the perceptible is always a masterstroke in van Empel’s work. Thus Van Empel rightly considers perfectionism as a imaginary, philosophical concept and not necessarily a merely simplistic, observable one. Striving for perfection is human, undoubtedly seductive and socially more topical and popular than ever. But the result today is plainly baffling. An observation that does not escape van Empel either.

Since perfectionism has become the social measure of things – the landscape, the living room, the partner… preferably all as perfect as possible – and in the process uses visual culture as a grateful and cheap accelerant, we also fall into the trap more than ever. A lot of people, not least strongly driven by a ruthless image culture that goes wild via social media, still do not understand why the perfect life does not exist and is unrealistic. Indeed, the perfect life is imaginary, elusive, unrealistic, let alone desirable. A realization that is barely gaining ground socially because the prevailing visual culture is eager to convince us otherwise.

When a goal is unrealistic – which perfection is – it even becomes potentially dangerous: “In an attempt to take a perfect selfie at a waterfall, five young women fell off a cliff in India. This recent and certainly not the last incident in the addictive search for perfection, in casu the perfect image, also indirectly illustrates the way we often look at Ruud van Empel’s “perfect” work. We are attracted by an idea of perfection but few see the real challenge. Indeed, the ‘technical perfection’ so much talked about in van Empel’s work is not a goal, but a deliberate means. An invitation, following the imaginary, philosophical concept of “perfection,” to look at other philosophical themes within Van Empel’s work in a way that transcends notions of technicality, analog or digital mastery.

Defiant imagination

So, what type of sculptor is up to this? What are we actually looking at when we behold Ruud Van Empel’s “perfect” images? The answer is as simple as it is complex: contrary imagination wrapped in stylistic, visually appealing concepts and ideas. For more than technique, genre or any other categorization we rather too often steal from the Great Register of Art History to say something about a photograph, this photographic work is a philosophical history of themes.

Van Empel turns temporal structures and universal themes inside out and proves how we can make images today from a much-needed trans literacy. Trans literacy understood as an artist’s position, as a conscious choice to adopt a literate and intellectual position within the prevailing visual culture. With and in images. But, as van Empel immediately adds, it is not only the making of these kinds of images that is important today, but also how we as viewers can look at images more critically and, above all, why we should look at images more attentively. In the way in which through this oeuvre, for example, the strongly evolving asymmetry can be deciphered in the relationship between those who look and others who are looked at, it seems as if van Empel has been challenging the ubiquitous visual gaze on its merits for almost four decades now.

All of these image series embody this asymmetry. Photo Sketch (1995- 2003), The Office (1995-1998, 2001), Study for Women – The Naarden Studies (1999-2000) or more recently Souvenir, Souvenir d’intime (2008, 2015) are issues that give van Empel’s oeuvre that special, philosophical temperament.

Complemented by van Empel’s views on themes that have been subject to seismic shifts in recent decades that are surfacing all over the world and, consequently, in the inseparable visual culture. We see those shifts in image series when van Empel clearly reflects on notions of cultural appropriation (Still Life, 2014-2015, 2017) or perfection versus imperfection (Theatre, 2010-2013). But also about nature as an undeniably political fact (Voyage Pittoresque, 2016-2019 and Floresta, Floresta Negra, 2018), a digital world that more than ever eludes the analog world (Unititled, Study in Green, 2003-2004), the artist who archives to forget (Generation, Wonder, Club, 2010-2011), molding the notion of beauty into a disturbing yet effective visual attack strategy in the face of narrow-minded notions (Collage, 2017) or abstract landscapes (Pollution, 2022) in which absolute freedom of expression manifests itself as a unique, slightly rebellious signature. They are reflections all contained in this body of work. Those who look back on this time, say fifty years from now, may find in van Empel a man of honor who perfectly captures the moral epoch in his oeuvre.

Moral rearmament

Ruud van Empel takes a challenging approach in every series. Never non-committal, but extremely thoughtful and usually on the basis of a playing field that repeatedly confronts you with a number of confrontational facts forces you to face a number of facts. In recent years, for example, World (2005-2008, 2010, 2017) received a lot of attention. Within the Christian tradition, the white child is a form of standard iconography to represent innocence. From the idea that black children are just as innocent as white children, Van Empel has visually redefined the concept regarding guilt and innocence.

World, which deals with black innocence, was already an unmistakable statement in 2005 that has lost nothing of its topicality to this day. On the contrary. In the wake of the worldwide events surrounding the death of George Floyd in 2020, that same black skin has become a political statement for many viewers. To many, what van Empel does in World is a form of gratuitous cynicism, but nothing could be further from the truth. Cynicism is a wry joke that dare not face the truth. Van Empel thinks differently. He is more human, more engaged and more sincere. He is, including with a statement like World, ahead of his time. Far away from any kind of cynicism. It brings me to a stimulating slogan: ‘The visual language of Ruud van Empel offers the moral rearmament that our visual culture needs’! Free of pomposity, populism and leaden moralism, but with a finely tuned sight towards people and their environment. A view that with Van Empel is characterized by reason and compassion and consciously reveals itself as a necessary plea for a new humanism. A humanism that recognizes the facts; we are improving overall, but at the same time also a humanism that fully realizes that we as humanity are firmly under pressure. Not least because of the prevailing skepticism and broad-based demagoguery that undermines confidence in scientific, inclusive and, above all, reasonable thinking. In Ruud van Empel’s work, it produces a form of magical thinking, a thinking around what is possible. For if we wish to continue to describe visual culture effectively as an expression of human expression, as well as communication between people, then Ruud van Empel’s oeuvre is an offer you can’t refuse.

In a quasi-uniform visual culture where everything is customized and personalized, Ruud van Empel’s work presents a beautiful paradox. Like a seismologist who scientifically records the vibrations in our visual culture and at the same time fully realizes that what you see depends not only on the context, your knowledge, your personality or your cultural baggage, but especially on the unpredictable moment. That’s where you make the difference as an artist. The moment when you decide to walk with the herd. Or not. And the latter has been a deliberate and masterful choice for van Empel for decades. Call it Van Empel’s avant-garde, a positively colored philosophy of life and an oeuvre that can be described as the necessary “experimental vanguard. Only in this way can Ruud van Empel carefully portray an image of the era. And meticulousness is far from perfection.

Christoph Ruys, former director of the Photography Museum Antwerpen FoMU

CV

Ruud van Empel

1958 Breda,The Netherlands, lives and works in Amsterdam

Education

Academy of Fine Arts Sint Joost Breda 1976-1981

Awards

1981 St. Joost prize

1993 Charlotte Köhlerprize

2001 H.N. Werkmanprize

2013 Municipality of Breda Oeuvre-prize

2017 Artist of the Year/American Friends of Museums in Israel-NYC

Solo Exhibitions (selection)

2023 STEDELIJK MUSEUM BREDA

2021 VAN GOGH HOUSE

2020 HANGAR ART CENTRE

2019 MUSEUM BELVEDERE

2017 JACKSON FINE ART

2017 BEETLES + HUXLEY

2016 FLATLAND GALLERY

2015 FOTO ART FESTIVAL

2015 BEETLES + HUXLEY

2015 PHOTO PHNOM PENH

2014 STUX GALLERY

2014 JACKSON FINE ART

2014 FLATLAND GALLERY

2014 NOORDBRABANTS MUSEUM

2013 FOTOGRAFISKA

2013 FoMu, FOTOMUSEUM

2012 MoPA-MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTS 2011 GRONINGER MUSEUM

2011 STUX GALLERY

2011 FLATLAND GALLERY

2010 NOORDBRABANTS MUSEUM

2010 ART+ ART GALLERY

2010 STUX GALLERY

2009 GALLERY TERRA TOKYO

2009 FLATLAND PARIS

2009 STUX GALLERY

2009 LEICA GALERIE LGP, PRAGUE

2008 CB COLLECTION ROPPONGI

2008 KUNSTVEREIN “TALSTRASSE” e.V.

2007 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2007 STUX GALLERY

2007 GALERIE RABOUAN-MOUSSION

2006 FLATLAND GALLERY

2006 JACKSON FINE ART

2006 STUX GALLERY

2005 NOORD BRABANTS MUSEUM

2005 DSM HOOFDKANTOOR

2004 TZR GALERIE FüR BILDENDE KUNST

2001 GALERIA BERINI

2000 CARTAGENA GALERIA

2000 ENCONTROS DA IMAGEM

1999 CARMEN OBERST KUNSTRAUM

1999 FOTOFORUM-ARMANDO MUSEUM

1999 GRONINGER MUSEUM

1998 TORCH GALLERY

Group Exhibitions (selection)

2021 PHOTO OOSTENDE

2020 GRONINGER MUSEUM 2020NRW-FORUM

2019 NORTON MUSEUM OF ART, W.Palm Beach 2019 MUSEO DEL PAESAGGIO

2018 MoCP Museum of Contemporary Photography 2018 PHOTOBRUSSELS FESTIVAL

2017 NASSAU COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART

2017 RIJKSMUSEUM VAN OUDHEDEN

2017 KUNSTHAL KAdE

2017 VICKI MYHREN GALLERY

2017 JOODS HISTORISCH MUSEUM

2016 COLLECTORS VIEW

2016 NRW FORUM

2016 PHOTOFESTIVAL BELA HORIZANTE

2016 PHOTOFESTIVAL ISTANBUL

2016 MoPA-MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTS 2016 FESTIVAL PORTRAIT(S)

2016 DE VISHAL

2015 UCONN, UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT 2015 MUNSTERLAND FESTIVAL

2014 MUSEUM DR.GUISLAIN

2014 YELLOWSTONE ARTMUSEUM

2013 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2012 MOTI MUSEUM

2011 SEOUL ARTS CENTER

2011 FUNDACAO BIENAL

2011 DANZIGER PROJECTS

2011 MUSEUM DR.GUISLAIN

2011 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2010LUMC

2010 SHAY ARYE GALLERY

2010 KUNSTHALLE DARMSTADT

2010 THE PORTSMOUTH MUSEUM OF FINE ART 2010 GORCUMS MUSEUM

2010 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2009 ANTI-CRISES AHA-KUNSTPROJEKT

2009 21C MUSEUM

2009 ULSAN CULTURE AND ARTS CENTER

2009 HANGARAM DESIGN MUSEUM

2009 THE JOHN AND MABLE RINGLING MUSEUM OF ART 2009 DARMSTäDTER TAGE DER FOTOGRAFIE 2008 MUSEUM KUNST PALAST

2008 ARTI ET AMICITIAE

2008 DES MOINES ART CENTRE

2008 NORTH CAROLINA MUSEUM OF ART 2008 SCHERINGA MUSEUM VOOR REALISME 2007 THE DAVID WINTON BELL GALLERY

2007 MoPA-MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTS 2007 BELLEZZA PERICOLOSA

2007 STUX GALLERY

2007 PINCHUK ART CENTER

2007 FOTOFESTIVAL NAARDEN

2007 GALERIE 4, GALERIE FOTOGRAFIE

2007 UNIVERSITY OF IOWA MUSEUM OF ART 2007 DES MOINES ART CENTER

2007 CHELSEA ART MUSEUM

2007 CATHERINE CLARK GALLERY

2006 STUX GALLERY

2006 THE ART OMI INTERNATIONAL ARTS CENTER 2006 HOUSE OF PHOTOGRAPY MOSCOW 2006 GEORGE EASTMAN HOUSE

2005 FOTO ANTWERPEN 2005

2005 GEM GEMEENTEMUSEUM

2003 PHOTOBIENNALE LIÉGE

2003 SCHERINGA MUSEUM VOOR REALISME 2003 FOTOFESTIVAL NAARDEN

2003 FOTOBIËNNALE ROTTERDAM

2002 UNIVERSITEIT VAN TILBURG, FAXX

2002 KUNSTHAL DE REMISE, SBK

2001 ART-TWENTE

2000 PRIMAVERA PHOTOGRAFICA

1999 FOTOMANIFESTATIE NOORDERLICHT

1998 ARTI ET AMICITIAE

Exhibition Catalogues and books

2020 25 YEARS OF PHOTOWORKS, Hangar/Book 2019 MAKING NATURE, Museum Belvedere/Book 2016 ARCHIVE-1980-2000, Ruud van Empel/Book 2016 SOUVENIR D’ITIME Gallery Catalogue

2015 RUUD VAN EMPEL Gallery Catalogue 2012 SUNDAY CHAPTER/Cahier

2011 PHOTOWORKS 1995-2010/Book 2011 WONDER/Catalogue

2009 PHOTOWORKS 2006-2008/Catalogue 2008 RUUD VAN EMPEL FOTOGRAFIE/Catalogue 2007 PHOTO SKETCH/Book

2007 PHOTO-ARCHIVE/Book

2007 WORLD, MOON & VENUS/Book

2006 WORLD MOON/Catalogue

2005 STUDY IN GREEN/Book

2001 PHOTO-ALBUM#1Photoseries 1996 - 2001/Book 1999 AFFICHE-ONTWERPEN/Catalogue

1998 THE OFFICE/Catalogue

1996 PHOTOGRAPHICS/Book

Collections (selection) USA

The Alturas Foundation, Chaney Collection

Des Moines Art Center George Eastman House Christian Louboutin

Jeff Morr Collection Maxine Taupin

MoPA Museum of Photographic Arts Nerman Museum

Pier 24 Photography

RCB (Royal Canadian Bank) in America Stephane Janssen Collection

The Netherlands

APG Collectie

Stedelijk Museum Breda

Caldic Collection

Collectie Erasmus Universiteit,

Collection Rabobank Groningen e.o. Collection Rabobank West-Flakkee, Collection Rabobank Midden Twente

DSM Art-Collection

DELA Kunstcollection

Eneco Energie

Flatland Foundation

Groninger Museum

Joods Historisch Museum

Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid

ING Real Estate Photography Collection

Isala Klinieken

Museum Het Valkhof,

Museum Voorlinden

Noordbrabants Museum

RIJKS Museum

The Essential Collection Rabobank Nederland The Hoboken Photo-Collection

The Netherlands Ministery of Foreign Affairs Vu MC Collection,

United Kingdom

Arad Collection

C-Photo Collection

David Roberts Collection

The Franks-Suss Collection

Sir Elton John Photography Collection Germany

Teutloff Photo + Video Collection

Austria

Generali Foundation

France

FNAC Collection

Switzerland

Catlin Collection

Spain

Colección Juan Redón

Fundación N.M.A.C.

Israel

Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Japan

CB Collection

1958 Breda,The Netherlands, lives and works in Amsterdam

Education

Academy of Fine Arts Sint Joost Breda 1976-1981

Awards

1981 St. Joost prize

1993 Charlotte Köhlerprize

2001 H.N. Werkmanprize

2013 Municipality of Breda Oeuvre-prize

2017 Artist of the Year/American Friends of Museums in Israel-NYC

Solo Exhibitions (selection)

2023 STEDELIJK MUSEUM BREDA

2021 VAN GOGH HOUSE

2020 HANGAR ART CENTRE

2019 MUSEUM BELVEDERE

2017 JACKSON FINE ART

2017 BEETLES + HUXLEY

2016 FLATLAND GALLERY

2015 FOTO ART FESTIVAL

2015 BEETLES + HUXLEY

2015 PHOTO PHNOM PENH

2014 STUX GALLERY

2014 JACKSON FINE ART

2014 FLATLAND GALLERY

2014 NOORDBRABANTS MUSEUM

2013 FOTOGRAFISKA

2013 FoMu, FOTOMUSEUM

2012 MoPA-MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTS 2011 GRONINGER MUSEUM

2011 STUX GALLERY

2011 FLATLAND GALLERY

2010 NOORDBRABANTS MUSEUM

2010 ART+ ART GALLERY

2010 STUX GALLERY

2009 GALLERY TERRA TOKYO

2009 FLATLAND PARIS

2009 STUX GALLERY

2009 LEICA GALERIE LGP, PRAGUE

2008 CB COLLECTION ROPPONGI

2008 KUNSTVEREIN “TALSTRASSE” e.V.

2007 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2007 STUX GALLERY

2007 GALERIE RABOUAN-MOUSSION

2006 FLATLAND GALLERY

2006 JACKSON FINE ART

2006 STUX GALLERY

2005 NOORD BRABANTS MUSEUM

2005 DSM HOOFDKANTOOR

2004 TZR GALERIE FüR BILDENDE KUNST

2001 GALERIA BERINI

2000 CARTAGENA GALERIA

2000 ENCONTROS DA IMAGEM

1999 CARMEN OBERST KUNSTRAUM

1999 FOTOFORUM-ARMANDO MUSEUM

1999 GRONINGER MUSEUM

1998 TORCH GALLERY

Group Exhibitions (selection)

2021 PHOTO OOSTENDE

2020 GRONINGER MUSEUM 2020NRW-FORUM

2019 NORTON MUSEUM OF ART, W.Palm Beach 2019 MUSEO DEL PAESAGGIO

2018 MoCP Museum of Contemporary Photography 2018 PHOTOBRUSSELS FESTIVAL

2017 NASSAU COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART

2017 RIJKSMUSEUM VAN OUDHEDEN

2017 KUNSTHAL KAdE

2017 VICKI MYHREN GALLERY

2017 JOODS HISTORISCH MUSEUM

2016 COLLECTORS VIEW

2016 NRW FORUM

2016 PHOTOFESTIVAL BELA HORIZANTE

2016 PHOTOFESTIVAL ISTANBUL

2016 MoPA-MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTS 2016 FESTIVAL PORTRAIT(S)

2016 DE VISHAL

2015 UCONN, UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT 2015 MUNSTERLAND FESTIVAL

2014 MUSEUM DR.GUISLAIN

2014 YELLOWSTONE ARTMUSEUM

2013 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2012 MOTI MUSEUM

2011 SEOUL ARTS CENTER

2011 FUNDACAO BIENAL

2011 DANZIGER PROJECTS

2011 MUSEUM DR.GUISLAIN

2011 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2010LUMC

2010 SHAY ARYE GALLERY

2010 KUNSTHALLE DARMSTADT

2010 THE PORTSMOUTH MUSEUM OF FINE ART 2010 GORCUMS MUSEUM

2010 MUSEUM HET VALKHOF

2009 ANTI-CRISES AHA-KUNSTPROJEKT

2009 21C MUSEUM

2009 ULSAN CULTURE AND ARTS CENTER

2009 HANGARAM DESIGN MUSEUM

2009 THE JOHN AND MABLE RINGLING MUSEUM OF ART 2009 DARMSTäDTER TAGE DER FOTOGRAFIE 2008 MUSEUM KUNST PALAST

2008 ARTI ET AMICITIAE

2008 DES MOINES ART CENTRE

2008 NORTH CAROLINA MUSEUM OF ART 2008 SCHERINGA MUSEUM VOOR REALISME 2007 THE DAVID WINTON BELL GALLERY

2007 MoPA-MUSEUM OF PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTS 2007 BELLEZZA PERICOLOSA

2007 STUX GALLERY

2007 PINCHUK ART CENTER

2007 FOTOFESTIVAL NAARDEN

2007 GALERIE 4, GALERIE FOTOGRAFIE

2007 UNIVERSITY OF IOWA MUSEUM OF ART 2007 DES MOINES ART CENTER

2007 CHELSEA ART MUSEUM

2007 CATHERINE CLARK GALLERY

2006 STUX GALLERY

2006 THE ART OMI INTERNATIONAL ARTS CENTER 2006 HOUSE OF PHOTOGRAPY MOSCOW 2006 GEORGE EASTMAN HOUSE

2005 FOTO ANTWERPEN 2005

2005 GEM GEMEENTEMUSEUM

2003 PHOTOBIENNALE LIÉGE

2003 SCHERINGA MUSEUM VOOR REALISME 2003 FOTOFESTIVAL NAARDEN

2003 FOTOBIËNNALE ROTTERDAM

2002 UNIVERSITEIT VAN TILBURG, FAXX

2002 KUNSTHAL DE REMISE, SBK

2001 ART-TWENTE

2000 PRIMAVERA PHOTOGRAFICA

1999 FOTOMANIFESTATIE NOORDERLICHT

1998 ARTI ET AMICITIAE

Exhibition Catalogues and books

2020 25 YEARS OF PHOTOWORKS, Hangar/Book 2019 MAKING NATURE, Museum Belvedere/Book 2016 ARCHIVE-1980-2000, Ruud van Empel/Book 2016 SOUVENIR D’ITIME Gallery Catalogue

2015 RUUD VAN EMPEL Gallery Catalogue 2012 SUNDAY CHAPTER/Cahier

2011 PHOTOWORKS 1995-2010/Book 2011 WONDER/Catalogue

2009 PHOTOWORKS 2006-2008/Catalogue 2008 RUUD VAN EMPEL FOTOGRAFIE/Catalogue 2007 PHOTO SKETCH/Book

2007 PHOTO-ARCHIVE/Book

2007 WORLD, MOON & VENUS/Book

2006 WORLD MOON/Catalogue

2005 STUDY IN GREEN/Book

2001 PHOTO-ALBUM#1Photoseries 1996 - 2001/Book 1999 AFFICHE-ONTWERPEN/Catalogue

1998 THE OFFICE/Catalogue

1996 PHOTOGRAPHICS/Book

Collections (selection) USA

The Alturas Foundation, Chaney Collection

Des Moines Art Center George Eastman House Christian Louboutin

Jeff Morr Collection Maxine Taupin

MoPA Museum of Photographic Arts Nerman Museum

Pier 24 Photography

RCB (Royal Canadian Bank) in America Stephane Janssen Collection

The Netherlands

APG Collectie

Stedelijk Museum Breda

Caldic Collection

Collectie Erasmus Universiteit,

Collection Rabobank Groningen e.o. Collection Rabobank West-Flakkee, Collection Rabobank Midden Twente

DSM Art-Collection

DELA Kunstcollection

Eneco Energie

Flatland Foundation

Groninger Museum

Joods Historisch Museum

Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid

ING Real Estate Photography Collection

Isala Klinieken

Museum Het Valkhof,

Museum Voorlinden

Noordbrabants Museum

RIJKS Museum

The Essential Collection Rabobank Nederland The Hoboken Photo-Collection

The Netherlands Ministery of Foreign Affairs Vu MC Collection,

United Kingdom

Arad Collection

C-Photo Collection

David Roberts Collection

The Franks-Suss Collection

Sir Elton John Photography Collection Germany

Teutloff Photo + Video Collection

Austria

Generali Foundation

France

FNAC Collection

Switzerland

Catlin Collection

Spain

Colección Juan Redón

Fundación N.M.A.C.

Israel

Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Japan

CB Collection

Free Magazine Subscription

Articles, interviews, shows & events. Delivered to your mailbox weekly.