04 january 2022, Flor Linckens

Kendell Geers: “I leave it up to the viewer to decide what they believe in, what they make of the ambiguity.”

Until 22 April, Amsterdam Art Gallery in Capital C has programmed the exhibition 'Voëlvy' ('Vogelvrij') by Kendell Geers, a collaboration with Galerie Ron Mandos. Due to government measures, a real-time visit is not possible for the time being, but on GalleryViewer you can still get a good sense of the works on display.

The practice of the South African artist Kendell Geers is perhaps best introduced by highlighting one of his most iconic works: “Self-Portrait” from 1995, the only official self-portrait he ever made. The execution of the work is surprisingly simple, but the message is sharp and clear. The work shows a bottleneck of a green Heineken beer bottle, broken into a sharp, pointy shape and effectively turned into a weapon. Larger than the brand it reads 'Imported from Holland', followed by 'The Original Quality'. Kendell Geers is a white descendant of Dutch settlers in South Africa and violence and identity are central to his practice, as is a razor-sharp and black sense of humour. Geers grew up in a South African working-class family during apartheid. At the age of 15 he became part of the resistance movement, in which he vehemently opposed the violation of human rights and the racist structures of meaning that he’d been taught as a child. After studying at the art academy, Geers fled his military service, and with it a six-year prison sentence. In 1988 he arrived in London as a political refugee.

Geers: “I knew that I would, in effect, be supporting a crime against humanity by going into the army. I decided at a very young age that there was no way I could use my body and soul as a violent weapon to defend the apartheid government. I think I was twelve or fourteen when it suddenly hit me, like a blinding flash, that my entire life had been based upon a lie, based on looking in the other direction when fascist policemen were horse-whipping black people as they rounded them up to check their pass books. My family, my eduction, my [Catholic] faith, my entire world was suddenly called into question and my world fell apart as I understood that everything I had been taught, every moral and truth that I was taught to believe in by my father, my teachers and priests, was in fact a lie and worse still, fundamentally morally corrupt. I lost my faith In everything and everyone as I understood they had all lied to me and colluded in one of the most violent crimes against humanity.”

Contradictions are central to the often confrontational work of the artist, whose inherited identity and character are also marked by contradictions. An African of European descent, someone who is inspired by punk culture as well as poets and philosophers. By literature and painting, but just as much by popular culture. Geers firmly believes that art is political and spiritual in equal measure. In fact, he uses his identity as a means to make us look at our history, art and language in a different way, using humour, irony and contradiction. He makes use of a broad frame of reference and a multitude of media; from installation art and sculpture to drawing, video, photography and performance. In his work, Geers asks questions about the discourse surrounding (art) history, the ways in which people give meaning to that same (art) history at an academic level. He criticises the role and ideology of museums and delves deeper into the language of power, religion and ideology. Moreover, his work is marked by what the artist considers to be the mirrored relationship between aesthetics and ethics.

After spending a year in London, Geers moved on to New York, where he worked as an assistant for none other than American artist Richard Prince. In 1990, after the release of Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners, he returned to Johannesburg, to a new democracy. The first artwork he made on South African soil was called “Bloody Hell”, a performance in which he washes his white African Boer body with his own fresh blood, while referring to what he calls the 'perversion of his own birth'. This ‘rejection’ of his birth is also reflected in other ways. During the Venice Biennale in 1993 — the first time that South Africa participated since the boycott of 1968 — Geers had his first name (Jacobus Hermanus Pieters) changed to Kendell and his date of birth to May 1968. That historic year of protest is widely considered to be an important year for the equality and liberation of people around the world. At the same time, the washing in blood serves as a reference to the famous ‘Invictus' poem that Mandela recited several times.

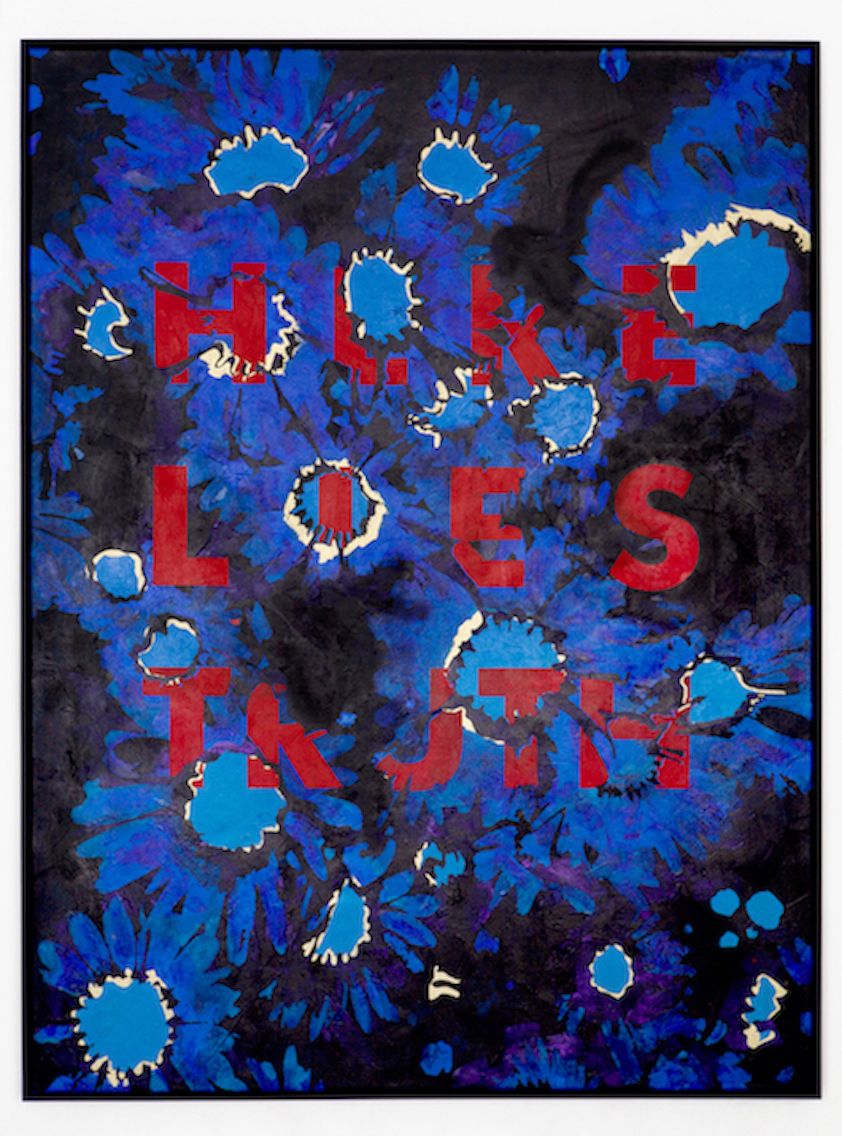

The exhibition at Capital C includes a work titled “Les Fleurs du Mal 2802” (2019). This title, 'The Flowers of Evil', refers to the book of poetry of the same name by the French poet Baudelaire. In the work, we see how decorative flowers conceal an underlying text: 'In God we Trust'. In another work from the same series, we also see flowers oppressed by a pattern that is reminiscent of barbed wire — a pattern Geers often uses and refers to the ways in which apartheid was historically enforced. In his work, the artist makes extensive use of the charged symbolism of violent elements such as barbed wire, broken glass, matches, black-yellow barrier tape, loose bricks and police batons. Materials that convey a certain urgency, disruption and danger and refer to (uneven) power relations. Geers believes that violence is the only way to bring about structural change, because as humans, we are programmed to take the path of least resistance.

Although Geers' work is marked by political implications, the artist does not recognise himself in the label 'political art'. He makes art that is characterised by a certain moral ambiguity, a political or moral issue that forces the viewer to make a choice and to take responsibility for that: what do you believe in? And why exactly? In the exhibition in Capital C, he literally asks us this question using one of his neon installations (“Manifest”, 2007): “What do you believe in?”.

Geers: “There is something unavoidable about the physical mass and presence of a loaded object that inhabits the same space as you but changes the way you negotiate that same space, making you aware not only of your body but also the way you understand the space you would otherwise take for granted. All good art is political in the sense that it challenges the ideologies and cultural prejudices of both the viewer and the artist. But my work is not political in the sense that I proclaim who I voted for or what I believe in - that would make me no better than a politician or a priest. The kinds of political work that I try to make are morally ambiguous and leave it up to the viewer to decide what they believe in, what they make of the ambiguity, the complicated morality. By entering into the work of art, the viewer participates by making a good/bad decision. Good/bad aesthetics. Good/bad morality. You are put into a position where your politics have to manifest in order to read the work by deciding whether it is a good thing or a bad thing, beautiful or ugly.”

In the late 1990s, Geers spent some time in Stuttgart, Leipzig, Berlin, Vienna and London. After the turn of the century, he took a year off, during which he read and thought a lot about art, politics and life — and the need to keep making art in an art world that is becoming more and more commercial. Geers: “A major shift took place sometime in 2000 when I decided to take a year-long break from making art. I started to reconfigure my idea of art as being less about politics and more a political reading of the being.” In 2003, Geers moves to Brussels, where he still lives and works. From that period on, his approach became more abstract, and language and spirituality began to play an increasingly important role in his art.

Geers: “If you look at each of my works individually you will never get it; you need to see the spiral that links what I am doing now with my very first works. Curiously, the people who do not understand my work are those that only know a little about art. The audience that responds best to it are either those that know absolutely nothing about art or else those that are extremely well educated. It’s important for me that my work functions almost in a kind of initiatory manner, that the more you search, the more you find.” ”

Geers' exhibition 'Voëlvy' ('Outlawed') by Amsterdam Art Gallery and Galerie Ron Mandos will be show in the Amsterdam Art Gallery in the Capital C building until 22 April - and online on GalleryViewer.