22 november 2021, Manuela Klerkx

Dale Lawrence | ‘Broken Tools’

Nuweland is currently showing the solo exhibition ‘Broken Tools’ by the South African artist Dale Lawrence (1988). Through his wall pieces, installations, and works on paper Lawrence presents his ideas about art as a set of tools for human communication and behavior including all complexities that go with it such as efficiency vs disfunction, violence vs healing and power vs oppression. ‘Broken Tools’ presents a series of works produced over the past six years and explores the possibility and impossibility of fixing established systems based on historical facts and human relations. Lawrence: ‘We like to ‘fix’ things. But you can’t fix broken things or a broken system unless you have broken tools. I mean, you can change or adapt a system, but if the system in itself is not ok, you don’t fix anything really.’

MK You have been in The Netherlands before. How is it to back again?

DL The other day I was thinking about the fact that everything works in this country. And that is new to me, being from South Africa. I have travelled quite a bit but the level of efficiency in The Netherlands is impressive and sometimes it makes me feel uncomfortable. Coming from South Africa, I am used to a lot of disfunction. And I realize now that a certain amount of disfunction creates room for questioning things, for addressing things as if they need to be broken, as if they don’t need to be fixed. If there is a strong belief that things are working, in a functional way, you don’t address the real things that lie underneath. We valorize efficiency as a way to fix our problems, as progression, as part of the future – whereas in reality, efficiency is the hyper purification of the systems that created the problems we want to fix.

MK You are a South-African artist who studied art in Cape Town. Can you tell us about about your artistic education?

DL I studied visual communication and graphic design at an advertising college, followed by fine art at university. The education structures in South-Africa are based on western ideas and methods but the processing and the responses come from a South-African perspective.

MK Can you illustrate this with an example?

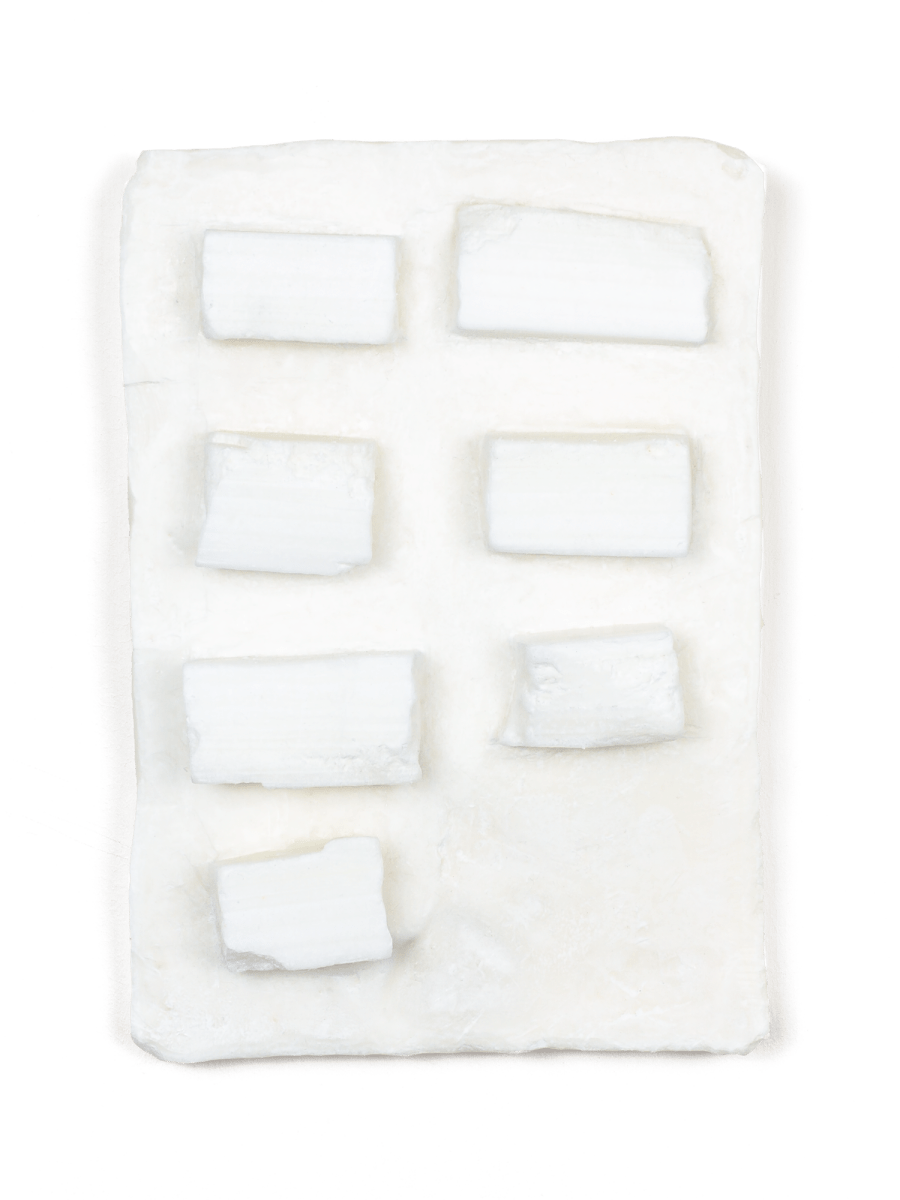

DL I'm inspired by and relate to Beuys' concept of creativity being essential to what it means to be human, or to be alive. Although I think that Beuys' utopian view falls short in its scope – in my personal view, maybe influenced by where I live - his vision is too simplistic in a world of ongoing and growing violence. For instance for Beuys, a material like fat represented healing and vitality. For me it represents the shifting acceptability of violence. I think Beuys failed to see that the same violence he condemned in humanity in the second World War is no different to the systematic slaughter of animals today, which we, as humans, may slowly but surely be waking up to. In Africa these utopian visions live visibly alongside continuing violence – not in an event that can be concluded like the European wars, but as a simultaneous everyday reality. Animal fat, when presented on the wall in a sculptural form, looks beautiful. But underneath lays a painful contradiction as the life-force of the material, its healing/feeding/wealth qualities are inextricably linked to the violence carried out on the animals in order to obtain this material. From a South African perspective I can see nothing but violence and greed in a material like fat: when I see fat on a wall I see silenced violence. I am interested in how, when you place fat on the gallery wall, it almost becomes ‘polite’; ‘innocent’ in a way. It looks beautiful like marble but it represents violence. So the material in itself is not ok. And this ‘not ok-ness’ is related to the ‘brokenness’ of the developed world in relation to countries such as South Africa. The ‘brokenness’ of the western world, its behavior and ways of thinking, has become our problem.

MK Where does the title ‘Broken Tools’ come from?

DL The title relates to the idea that we like to ‘fix’ things. But you can’t fix broken things or a broken system unless you have broken tools. I mean, you can change or adapt a system, but if the system in itself is not ok, you don’t fix anything really. Cultural systems inform political and economic systems, by that I mean culture precedes politics and economics, it becomes them. In that sense, art is primary as art has a direct role in addressing issues about power and violence.

MK There is often a dual relationship between different objects in your work. As if you want to visualize a dialogue between different realities or thoughts.

DL That is right. The material of the fat for instance, mirrors other conjunctions in the exhibition: that of the two chairs, one with extended and the other with shortened legs, and of the framed relief Lino-cut print and the destroyed printing block. They are all elements of the same process: they go together because they are part of the same system. Just like the two rugby jerseys hanging on the coat rack represent Post-Apartheid South-Africa symbolized in the persons of Nelson Mandela [a legendary anti-apartheid revolutionary and first black president elected in a democratic election, MK] and Francois Pienaar [a famous South African rugby football player who led the South African national team to victory in the 1995 Rugby World Cup, MK]

Dale Lawrence, Tragedy of the Rainbow Warriors (after Jannis Kounellis and Francois Pienaa), Nuweland.

MK Can you explain the piece ‘Tragedy of the Rainbow Warriors (after Jannis Kounellis and Francois Pienaar)’ with the Lay’s chip packets Springbok supporters jerseys, a shelf, an oil lamp and a coat rack?

DL That piece has directly to do with the groundbreaking influence artist Jannis Kounellis (1936-2017) had on my artistic development and this conversation between him and Joseph Beuys that sums it up. They were talking about the Cologne cathedral as a symbol for people to connect with each other. It stands for a common belief – whatever that is. I learned that the cathedral was the only building in Cologne not destroyed during the Second World War. While the entire city was flattened and left blackened, the cathedral in that moment transformed into a symbol in the same way Kounellis’ considers art: the cathedral went from something that was a design to something that was a container of historical facts and social relations.

The bombing of the cathedral and the destruction of the city were actually the art piece. I found that vision very liberating and it challenged me to put more gestures, more layers, into my work and to relate to the world in a more concrete way. I wanted to add more meaning to my work, not based on narrative images but on a combination of gestures concentrated within a space. Like the cathedral I started seeing each of my works as symbols for my ideas. The work with the Lay’s chip packets and the coat rack is a direct reference to the ‘Tragedia Civile’ by Jannis Kounellis which I interpreted from a photograph and adapted to my own, entirely South African interpretation as it directly relates to the democratic elections held in South Africa in 1994 and the winning of the Rugby World Cup in 1995. The fact that our team won the world cup was for South-Africa a solemnification of the elections that had marked the official end of Apartheid. The moment that Nelson Mandela handed the winning trophy to the rugby team captain Francois Pienaar symbolized our belief that we had successfully eradicated Apartheid and that we as a nation could finally move on with our lives. And that idea, in my opinion, happened to be a fatal mistake.

The Springbok supporters jerseys hanging on the coat rack make reference to the figures of both Mandela and Pienaar who also wear South African jersey clothing, and also to the jerseys hanging in the wardrobes of South Africans today, waiting for new opportunities to relive that moment. But the wall is covered with chip packets instead of, like in the case of Kounellis’ piece, gold-leaf. And that has to do with the fact that after winning the world cup, Francois Pienaar used his success for commercial purposes. He became the figure head of Lay’s chips in their advertising.

From the moment Apartheid was officially abolished and the international sanctions were lifted, not only could we take part in international sports again, but also new consumer goods started to flood into the country. These material goods immediately started to be purchased by middle-class white South-Africans as status symbols. So people started to unconsciously equate the end of Apartheid to material health, which led to the idea that being good (not a racist) – apparently – comes with material benefits.

What I want to say is that Kounellis’ work, to me, represents the expectations, and the weight of history on one hand and the ideas and limitations of the individual artist on the other. The first time I displayed this work in 2019, I replaced Kounellis’ paraffin lamp with a mobile phone with a lot of news apps announcing all kinds of crises related to murder, violence, environmental issues, and so on.

For this exhibition however I reverted the installation back to a paraffin lamp in reference to the way South Africa’s power utility is crippled by debts and corruption, and by consequence linked to poverty. The interior walls of many informal homes in South-Africa – without electricity, are often pasted with newspapers or other consumer goods packaging. I wanted to focus on the paraffin lamp and the chip packets being symbols of power vs poverty.

MK What do the paper work with the words written in ink tell us?

DL They are based on the belief of American artist Sol LeWitt (1928-2007) that art is about mental processes and systems that should be executed by clear instructions an artist needs to respect. When I started myself thinking about what it means to make art I realized that it is far more complex than just a rational system conceived and executed by an artist according to strict rules. So I started to amuse myself writing down the emotional aspects, the doubt, the revision of a system. In my point of view art is not related to a system but to living. In other words, the understanding of art is related to the acknowledgment that life itself is what counts.

I feel an affinity to abstract and conceptual art but in ways that are more gestured and lively than most of the artworks I see in Europe and Northern-America.

MK Can you tell me something about the work called ‘Self-portrait under the Lamp’ consisting of a desk, hanging high up in the air, with a lamp sitting on it, shining upon a very small chair downstairs?

DL The desk to me represents the establishment, expectations: work that needs to be done according to my position as an artist. The chair though is where I find myself in real life. There is an obvious disconnection between the two. I think the work relates to the responsibility I feel being an artist but also to the impossibility of the task at hand, which I expressed by the lamp I placed on top of the desk that stares down at the chair in an interrogating fashion: the light is illuminating but also accusing. On the desk is a meat grinder, a fossilized mammoth tooth, a ceramic dodo and a ‘stone’ I made out of many layers of box tape. The material and objects were sourced intuitively. I think there is something illuminating in the way one gathers things in a spontaneous way. The convergences around these objects create a kind of a story. For instance I made the box tape stone before I ordered the fossil mammoth tooth online, and the two materials share a strange resemblance. What I mean to say is that one person can not resolve all problems but we can, literally and metaphorically, shine a light on them by doing the best we can. So this piece in a way addresses the weight of expectation, of responsibility.

MK And what about the piece with the small and the big chair?

DL This piece is contains two chairs placed in front of each other, poised for conversation. You could say that one has taken the legs of the other to elevate itself. What strikes me in this arrangement is that neither one is in the right position: on one you would sit with your legs dangling, on the other your are more or less on the floor. Neither one is benefitting from its situation. It shows that the elevation of some comes in despite of others. This recalls the unequal relationships of colonialism, which in fact is still alive and happening.