21 november 2025, Emily Van Driessen

Experience Pavel Büchler’s new exhibition at Tommy Simoens Gallery

What does it mean to notice the moments in which ‘nothing’ happens?

Pavel Büchler’s new exhibition Experience at Tommy Simoens Gallery in Antwerp brings together works from 1999 to 2025 that linger around the invisible tangibility of time, sound and absence. It’s a compact retrospective of key pieces that trace what remains in between: the anticipation before a concert that never starts, the soft spin of a record before the music starts, the rattle of applause without performance, the tiny mechanics of trying to capture time.

The exhibition unfolds like a conversation that never quite takes place, an ungraspable, almost spectral exchange with three key figures of twentieth-century art and thought: Samuel Beckett, John Cage and Marcel Duchamp. Together they form a loose framework through which Büchler’s clever, inventive, and disarmingly precise works register his intricate studies of how experience clings to things most of us no longer notice.

Pavel Büchler, Experience, Tommy Simoens Gallery

Time

Writer Samuel Beckett is perhaps best known for Waiting for Godot, a play in which two characters wait for someone who never arrives. His writing is stripped down, repetitive, often circling around failure, boredom and the impossibility of progress. Almost nothing happens on the surface, yet everything is at stake in the way time stretches and language falters. In Bühler’s work, Beckett doesn’t function as a literary reference but more as an attitude with an insistence that repetition and failure are not obstacles to art, but the very material from which it is made. This attitude becomes tangible in several works throughout the exhibition.

Table ↔ Turntable (1984–2025) brings together six simple studio diagrams showing where Büchler placed his desk and his record player in every workspace he occupied since the mid-1980s. Each drawing records only this small relationship, but layered together they map four decades of his routinous working life. What looks at first like an architectural plan becomes almost a self-portrait. The work turns the most ordinary studio habit — arranging two pieces of furniture — into a long, slow record of how an artistic practice is lived.

Pavel Büchler, Table ↔︎ Turntable, 2025 + Veterans, 2021, Tommy Simoens Gallery

The diptych Veterans (2021) takes this further into the language of painting. Büchler removes the dried paint from found canvases, grinds it down and spreads the residue over the stripped surface of the same canvas. He creates paintings out of the failure of other paintings, a literal recycling of the past. It becomes a study of how material carries ‘value’, even when its original image has vanished.

In Beckett’s Cage (2019) he makes the Beckett reference explicit. Two letterpress prints, hung with a deliberate gap between them, divide a short sentence from Beckett’s text Imagination Dead Imagine: “a pause, more or less long”. The pause suggested by that phrase is enacted spatially by the blank wall between the sheets, and visually by the excess of white space around the words. Nothing happens, yet that nothing is very precisely framed.

Sound

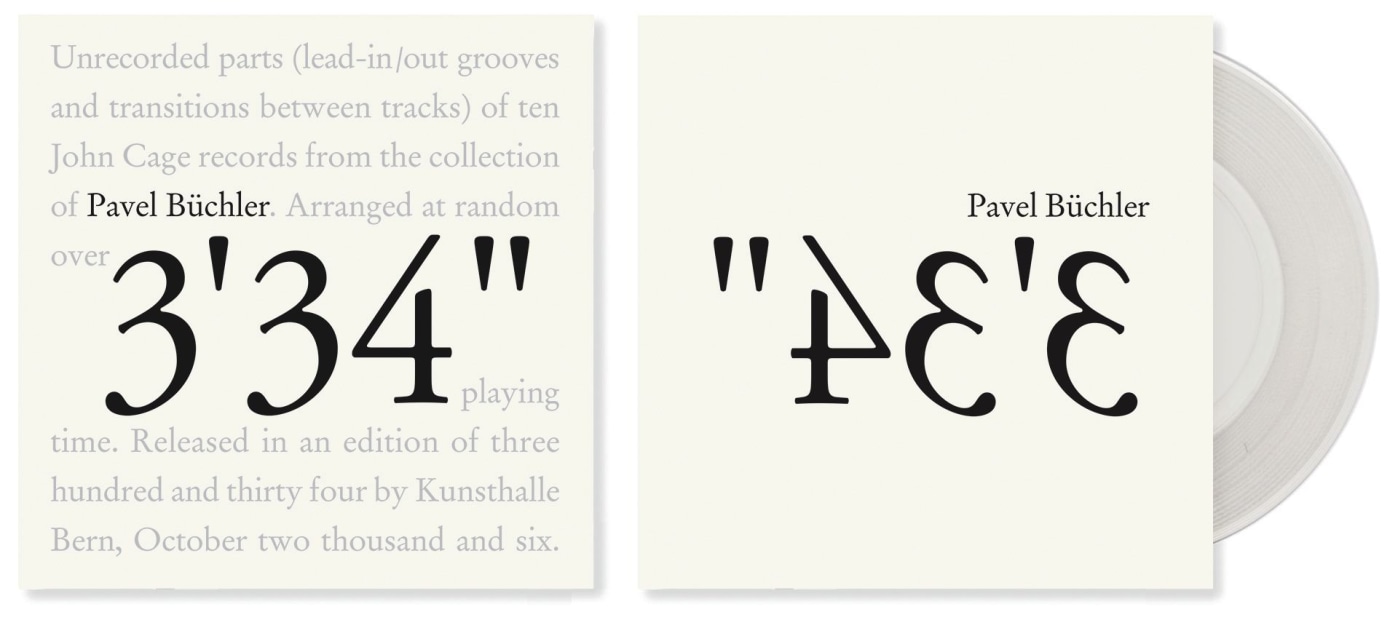

Experimental composer John Cage radically expanded the ways we listen, treating silence, ambient sound and duration as integral parts of a musical experience. His most famous piece, 4’33”, consists of a performer not playing their instrument for four minutes and thirty three seconds. The “music” is whatever sounds occur in the room during that time, from coughing to traffic in the distance. Büchler’s engagement with Cage runs through several works in the exhibition, each of them circling around the fragile thresholds between sound and/or its tangible absence. A few works bring this sensibility into focus: 3’34” (2006) is made entirely from the lead in grooves of ten John Cage records. These are the bands of vinyl that the needle runs through before the track begins, a zone usually treated as empty. Büchler cuts them together into a single record, so that what we hear is a barely audible texture of hiss, clicks and surface noise. The piece literalises Cage’s invitation to listen more closely, while also recording the wear of repeated use. The tiny sounds are an index of how often those albums were played.

Pavel Büchler, 3'34, 2006, Tommy Simoens Gallery

The Score (2008) translates the duration of 4’33” into a typed grid of time codes that ends, precisely, at 4 minutes and 33 seconds. It looks like a minimalist conceptual drawing, but it also hints at performance; someone had to type all those numbers. It is almost impossible to do so in real time, so the work subtly misaligns written time with lived time. Silence, here, becomes something that can be counted, but never fully inhabited.

In Lou Reed Live (2007) the relationship between sound and expectation is stretched further. The work sets up what looks like a small stage; a microphone on a stand, a tape machine on the floor, a loop of exposed tape. From time to time you hear the scratch of a match, an inhaled breath, a soft “hello” from Lou Reed, taken from his live album Take No Prisoners. The concert, however, never starts. The microphone does not record, it plays back. Presence and absence are reversed. What remains is a suspended prelude: a permanent “not yet”.

In the records LIVE (1999) and ENCORE (2005) Büchler strips away the music entirely and edits together only the applause from live albums in his collection. The result is a disorienting flood of clapping and cheering from different rooms, decades and crowds, with no performance to anchor it. Anticipation and gratitude are there, but their cause has disappeared. It is a kind of social 4’33” in reverse, a portrait of audiences without a stage.

Pavel Büchler, Lou Reed Live, 2007 + Dear Mr. Cage, 2005, Tommy Simoens Gallery

Absence

Marcel Duchamp is the artist who shifted the centre of art from making objects to thinking about them. With his ready-mades and linguistic experiments, he reframed art as an idea. Less known, he also developed the notion of inframince, the almost ungraspable difference between two states or moments. Büchler’s work repeatedly returns to such faint residues of barely perceptible change.

Büchler’s new piece Experience (2024), also the exhibition’s title, goes back to his youth in 1970s Prague, where Western rock music circulated as illegal cassette copies. Bands like Jimi Hendrix reached listeners through endlessly recopied tapes full of distortion and hiss. In 1984, after moving to Britain, Büchler realised that the “clean” version of Hey Joe he heard on the radio no longer resembled the one he grew up with. For a whole generation, the sound of a song was inseparable from the noise of its damaged medium. Decades later, Büchler presses a vinyl single that contains only the surface noise of Hendrix’s “Hey Joe”. All music is removed and what remains is the ghost of a collective listening experience.

Pavel Büchler, White Label, 2003, Tommy Simoens Gallery

White Label (2003) reduces the image of a vinyl record to a simple projection; a circle of light with a dark disc at its centre, produced by a slide in a carousel projector. The work links two obsolete technologies, the record and the projector, and allows both to appear only as outlines. The “content” has drained away, but the form of playback persists as a diagram.

TONIGHT (2003) begins with a small, worn street sticker Büchler found on the pavement after a night out in Manchester. Its loud promise “TONIGHT!” had already expired by the time he picked it up. By enlarging this discarded fragment into a full poster, he shifts attention from the event it once promoted to the material traces of the sign itself. The work links back to the long history of poster culture: walls layered with outdated announcements and overpasted adverts that carry the residue of past promises. In Büchler’s version, the urgency of an upcoming event collapses into a faded after-image that now points to nothing.

Experience is on view at Tommy Simoens Gallery until Saturday 20 December.

Pavel Büchler, Experience, 2024 + TONIGHT, 2003, Tommy Simoens Gallery

About Pavel Büchler

Pavel Büchler (b. 1952, Prague; lives in Manchester) is a Czech-British conceptual artist, writer, and educator, often describing his practice as “making nothing happen.” After leaving Czechoslovakia in 1981, he became a key figure in UK conceptual art, co-founding the Cambridge Darkroom gallery and later leading the School of Fine Art at Glasgow School of Art. His installations, text works and re-purposed everyday objects uncover the uncanny in the ordinary. Notable works include the ongoing series Work (All the cigarette breaks…) (2008–), exhibited in its most recent iteration at Gallery of Fine Art Cheb. Recent solo shows include Signs of Life (Cheb, 2024; Brno, 2023), Level (Florence, 2022) and New Paintings (Tommy Simoens, Antwerp, 2018). Group exhibitions include the Lyon Biennale (2024), Transmediale (Berlin), MuHKA (Antwerp), and DOX (Prague). Awards include the Northern Art Prize (2010) and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award (2012). His work is in public collections including Tate, MoMA, Arts Council England, and the National Gallery Prague.