07 october 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

Shakespeare’s Sisters: Marenne Welten at tegenboschvanvreden

To Welten, her work is all about play and imagination, not a literal translation of an image into paint. “I want there to be more to see than what you see, for something to start stirring within the viewer’s imagination.”

Shakespeare’s Sisters is Marenne Welten’s first solo exhibition at the tegenboschvanvreden gallery. It is also the final part of a four-part cycle revolving around her childhood home and the period following her father’s death. While the first three projects focused on her father and explored themes such as loss, waiting and alienation, in Shakespeare’s Sisters Welten turns her attention to the women in her family who have been important to her.

The artist’s book Shakespeare’s Sisters will be presented at the finissage on Saturday 18 October at the gallery.

Your current exhibition, Shakespeare’s Sisters, deals with memories of family members and interiors. Why did you want to create a series around these themes?

To me, an interior is a psychological space. The inhabitants are moulded by the space and vice versa. That’s why I am interested in the childhood home—especially the living room, kitchen and bedrooms—as an imprint of the people who lived there, myself included. I use and rearrange the rooms and furniture to stage and direct characters in different settings. At first, I mostly painted empty spaces; later, I began adding figures.

Did you have a clear starting point or did the subject emerge as you worked?

Shakespeare’s Sisters follows three previous projects. All four projects and the exhibitions that resulted from them share a common theme: the parental home and the period after my father’s death. In the first three projects, the focus was on my father, but they also dealt with adolescence, loss, waiting and estrangement.

In the fourth project, Shakespeare’s Sisters, I introduce women from my family who were important to me. To mark the completion of these four interconnected projects, the artist’s book Shakespeare’s Sisters has been published and will be presented during the finissage at the gallery on Saturday 18 October.

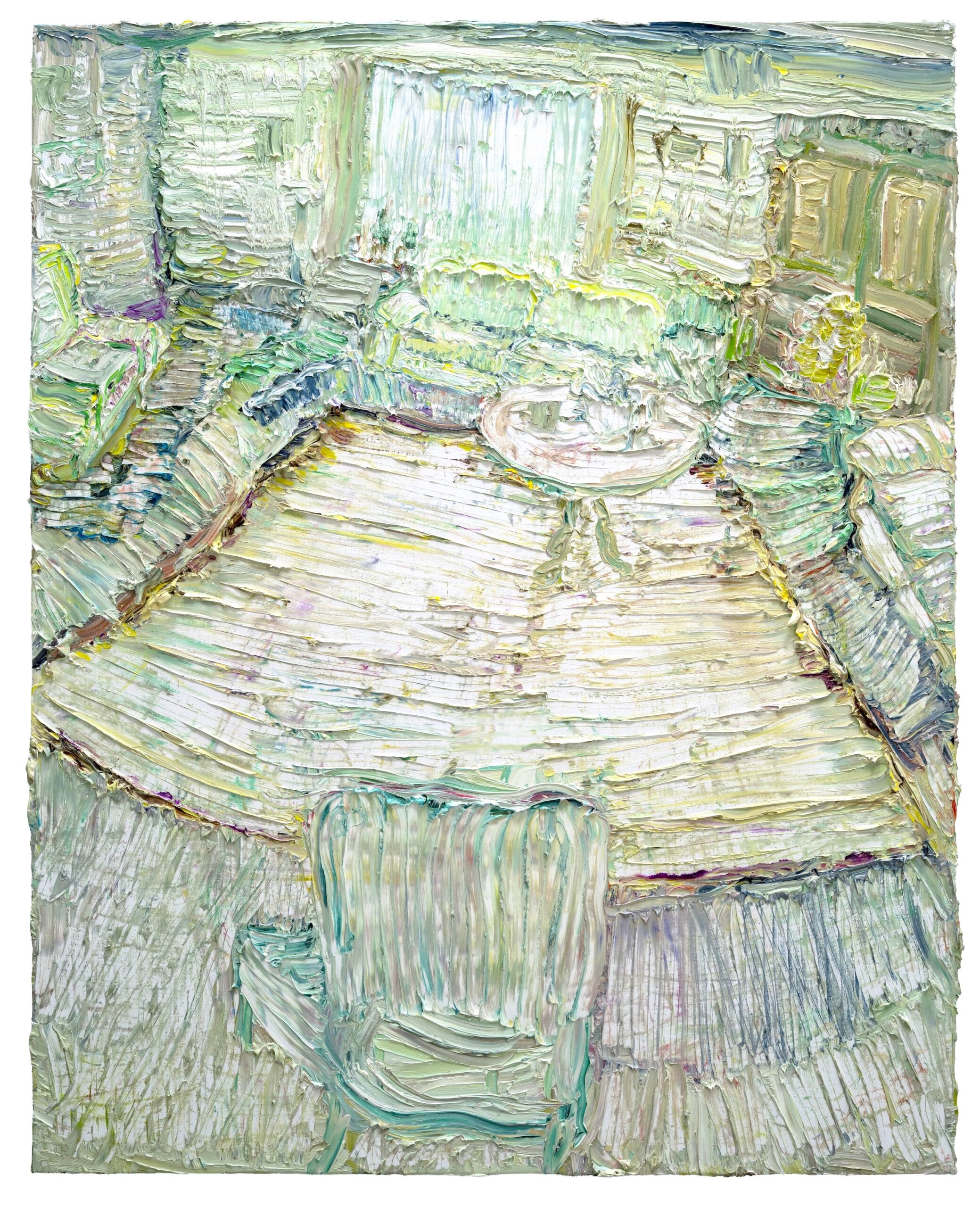

Marenne Welten, Dinner Table, 2025, tegenboschvanvreden

Could you tell us a bit more about the emotional charge of your family’s living room?

My father died when I was eleven. His death was largely met with silence. Everything that remained visible of him—his sculptures, his car, his shoes, his clothes—acquired added weight through his absence. It was like an archaeological excavation: unearthing the objects he left behind, mapping and painting those artifacts. Paul Auster wrote a beautiful book about this called The Invention of Solitude.

Even now, I often wander through the childhood home in my mind. I see the rooms and details before me like a film. I use them in my paintings—it’s an inexhaustible source. Years ago, I had an important dream about painting. The dream showed me the living room of my childhood home, but through the eyes of a painter: in terms of form, composition, contrast, colour, lightness and mass.

At the back of the gallery hangs a large painting of a living room titled When My Aunt Left the Room, but there’s hardly any red left on the carpet. The smaller painting next to it, Red Carpet, is the same. What’s going on there?

In both paintings, the red of the carpet has been painted over or scraped away. It depicts my late aunt’s living room, which had a red Persian rug. I find red a difficult colour—it can dominate an entire canvas. So, I took the liberty to remove it. The funny thing is, I know it’s red and because I refer to it in the title, the viewer knows it too. I’m not finished yet with the visible/invisible red of that carpet.

Marenne Welten, When My Aunt Left The Room, 2025, tegenboschvanvreden

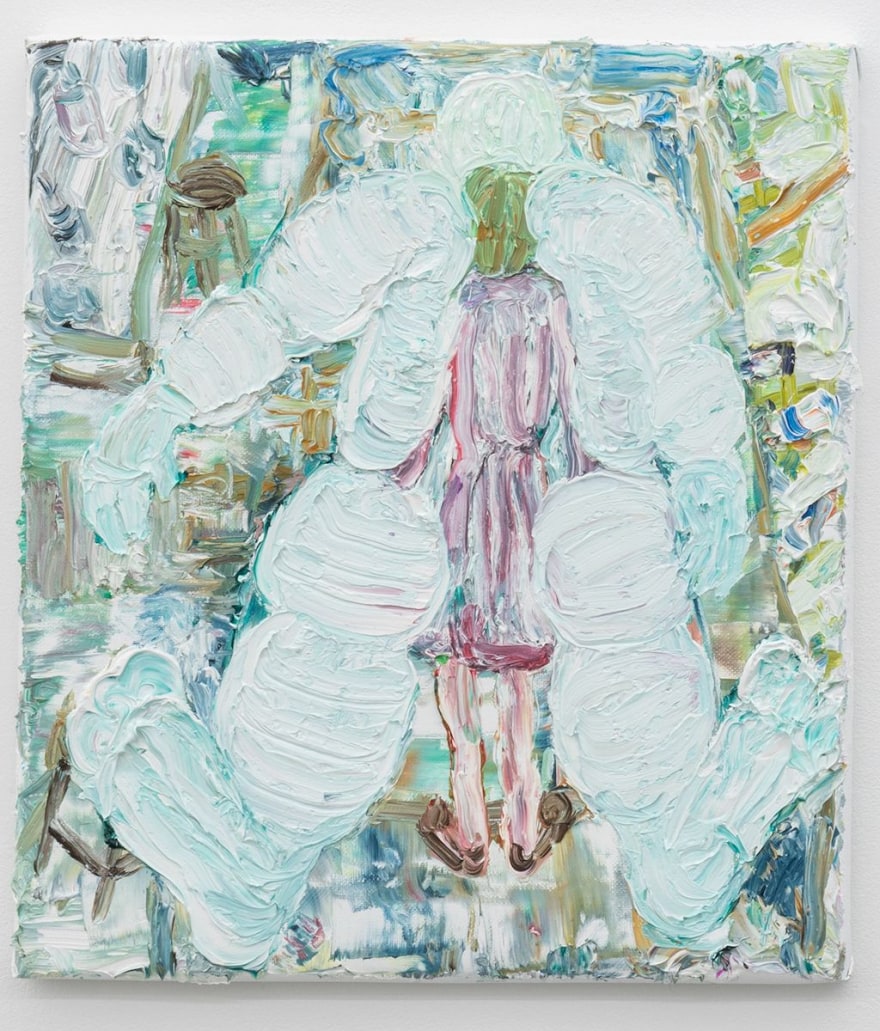

The exhibition is called Shakespeare’s Sisters and focuses almost exclusively on your female relatives.

In the previous three projects, my focus was on my father. Occasionally, you’d see a foot belonging to my mother or a small detail of my aunt. When I started this project, I realised that I hadn’t paid enough attention to the women behind the scenes. The title Shakespeare’s Sisters refers to Virginia Woolf’s book A Room of One’s Own, in which she speculates about what might have happened if Shakespeare had had a sister with equal talent—would she have had the same opportunities as her brother?

I realised that the postwar generation of women in my family had far fewer opportunities because of the time they lived in. What would have happened if it had been my mother, not my father, who went to art school? How did my mother and aunt feel about the fact that I had the freedom to go to art school, to live with a partner, to travel?

You mentioned earlier that you couldn’t work with the red Persian rug and decided to remove the colour, leaving a white surface. Does this also apply to the portraits in the exhibition? Are they faithful representations or is that not important to you?

In the past, I sometimes based my work on a photograph, but later in the process, I realised that a photograph just gets in the way. Once I have an image in mind, I begin to mould it mentally into how I would want it to appear in paint. When I start to paint, I let go of that image fairly quickly. It’s fascinating: as a painter, I have to surrender to the process, to a kind of logic-free state, yet I also need an extra eye to maintain some level of oversight. It’s a constant navigation between those two extremes.

Philip Guston compared the act of painting to being under the influence of drugs and I think he’s right. While painting, I find myself in an unknown part of myself that I have no access to in daily life. I may begin with a clear intention, but it’s always a surprise where I end up.

Let’s talk about your painting style. It’s quite unique. When people talk about thickly applied paint, they often use the word ‘painterly’ or ‘impasto’, but that doesn’t seem sufficient here. You apply paint in thick layers and then manipulate it. How did this style develop? Is it inspired by your background as a sculptor?

It began in 2012 when I showed Hendrik Driessen a series of small new paintings. He invited me to hold a solo exhibition—It Is Not Allright (2013/14) at Museum De Pont—on the condition that I would paint for the show rather than draw. For that project, I mainly painted empty spaces, using a lot of medium to make them appear spatial, though they were actually flat. The white areas of the small canvases were the exposed raw canvas itself, visible where I had pushed and pulled the paint across the surface.

After a while, around 2017, this no longer satisfied me—I wanted the paintings to become physically dimensional as well. I began each canvas with a thick layer of white paint, onto which I applied colour. This added a complication: thick wet paint is slippery and the colour sinks into the creamy white. As a painter, I seek a certain resistance. A painting shouldn’t be too compliant. The paint kneads the subject, the subject sinks into the paint and resurfaces again.

Marenne Welten, Super Woman, 2025, tegenboschvanvreden

One of the challenges you set for yourself is making so-called ‘Remake’ paintings—two of which are shown in the gallery—using paint that has already been mixed and scraped from your canvases.

That ‘residual paint’, once scraped off, has an indeterminate colour. When you first see it, you think: a mud pool—no painting can come from this. But my curiosity pushes me to make something out of an unknown form and colour, to face challenges during painting. The essential moment in painting is when it threatens to ‘fail’ and I, as the painter, have nothing left to lose—that’s when I dare to keep going.

Because of the thick layers of paint you work with, your work feels tactile yet elusive—like a memory. The viewer can’t take it in all at once.

I like that my work meanders. It forces the viewer to refocus their eyes again and again. It’s about play and imagination. I’m not interested in a literal translation of an image into paint. I want there to be more to see than what you see, something that starts to move within the viewer’s inner world.

Welten refers to the English poet Ted Hughes, who in a letter to his daughter Frieda explained that a faithful depiction of an experience has less expressive power than one that is more universal. He advised her to “fish around and experiment”, because attempts to express emotions directly tend to be stiff and inauthentic: “The emotions of the real experience are timid, but once they find a mask they become shamelessly exhibitionist. A feeling seeks a metaphor for itself in which it can reveal itself unrecognisably.”

Finally, in recent years, your work has received growing attention, also abroad. How does it feel to be in the spotlight somewhat later in life? Does that have advantages compared to an early breakthrough?

I’ve wondered about that myself. I only began painting seriously after 2010. Before that, I painted occasionally, but always stopped, feeling that I didn’t yet have enough baggage. It’s hard to answer a ‘what if’ question, there’s no real answer to that. I can only look at my work and see how it has developed over the years. I realise it couldn’t have gone any other way, as each project connects to the next in a natural progression. The larger structure of the work becomes visible over time. That brings a certain calm.

You might compare it to a house with many rooms. In my painter’s life, I wandered through all the rooms, curiously opening one door after another. I gathered things from each room and carried them into the main chamber, like a magpie with its treasures. Until one day I realised how far I had drifted from that main room. I then returned to explore what was there. That room was crammed with objects, props and baggage. I decided to start working with what was already there.

Marenne Welten, Night, 2024, tegenboschvanvreden