03 october 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

Erasing in history: the historical revisionism of Inez de Brauw

Historical revisionism is not exactly a subject that dominates the daily news—or is it? Until recently, the impact of a new perspective on a historical subject was largely limited to a small circle of historians and well-informed enthusiasts. But that has changed over the last 10 to 15 years. The past has become the focal point of national debate. Historical revisionism is now called ‘decolonisation’: the reinterpretation of the Western colonial past and all the accompanying assumptions, interpretations and concepts that still resonate today.

The best-known Dutch example is the heated debate around Zwarte Piet, seen by some as a symbol of oppression and by others as a cherished tradition. In the museum world, this revision of the past translated into displaying different works than before, emphasising alternative perspectives, implementing more diverse HR policies and adopting new acquisition and deaccession practices. For example, the first major acquisition by Stedelijk Museum Director Rein Wolfs was a work by Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui. The Rijksmuseum is now devoting more attention to female painters from the 17th century than in the past. And in photography, Swiss-American nanny Vivian Maier has been posthumously discovered and added to the canon.

Although Inez de Brauw’s work relates only indirectly to these developments, she does something entirely different. This Rijksakademie alumna takes well-known 17th-century paintings of art chambers as her starting point and repaints them in grayscale. She then reworks each painting by altering the representation of power relations. Figures and objects she considers important are painted in colour, while traditional power figures are rendered in black and white.

Antwerp painters such as Willem van Haecht (1593–1637) and David Teniers (1610–1690) were often commissioned by prominent figures to depict their collections in a single painting, displayed in a showpiece room. This genre was especially popular in the southern Netherlands. The works not only portrayed paintings of relatives, but often included people: the commissioner, the patron, family members, dignitaries—and always, somewhere, a dog. Cornelis van der Geest, patron of Peter Paul Rubens, for example, hosted Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Habsburg, governor of the Spanish Netherlands, while Willem van Haecht painted.

These gallery paintings contained a wealth of codes we are no longer always able to decipher. A dog, for instance, symbolised good manners, chastity and influence. The bigger the dog, the more important its owner. Some codes were more persistent and endured over time.

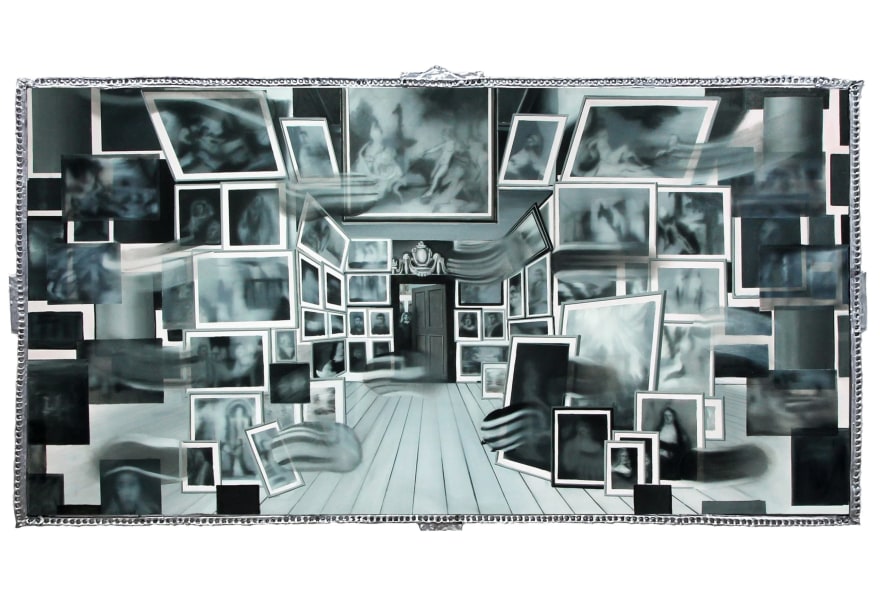

Inez de Brauw, Camparse - Image Seize, 2025, Galerie Fontana

The first large work you see on entering is based on Van Haecht’s Apelles Paints Campaspe (c. 1630). The scene depicts the myth of Campaspe, mistress of Alexander the Great. According to the story, the painter Apelles fell in love with her while painting her portrait. The result was so beautiful that Alexander gifted Campaspe to Apelles. The myth symbolises the exalted nature of painting.

In Van Haecht’s painting, Campaspe radiates beauty and chastity. “You still see that today: sit nicely and just be beautiful. She was given quite a dumb role,” says De Brauw. It’s a role with which De Brauw cannot identify. Instead, she identifies with a woman on the far right holding a paintbrush. In De Brauw’s version, she holds the reins, deciding who is highlighted and who is not. Myths like these were often included in 17th-century gallery paintings to demonstrate that everything was proper and morally upright. For a 21st-century viewer, however, such notions are heavily loaded, given that part of the wealth originated from slavery.

Inez de Brauw, Borrowed Light, 2025, Galerie Fontana

The message may be fairly political, but De Brauw’s painterly interventions are playful, making the work accessible. In another piece, based on Van Haecht’s The Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest (1628), a viewer kneels to study a miniature version of the gallery painting we are looking at. He circles the details that deserve attention. Those circles reappear in the larger composition. In another work, someone seems to have wiped away a layer of dust with their finger, revealing colour beneath—like someone drawing on an iPad.

The Muse Withdraws marks a new phase in De Brauw’s oeuvre. She calls it erasing in history. “I wanted painting to play a role in the story I wanted to tell,” she says about a canvas on which the artist has added numerous white blocks and shapes to the composition. “I wanted everything to have more colour, to be looser, less formal.” In the first painting she worked on, the figures were still absent and the lines more rigid.

De Brauw also stresses that this series is deeply personal. Last year, she ended a long-term relationship, after which she did a residency in Leipzig and started therapy. “This was formative for the series because I had to retell my own story, my own history. I had to examine who I was, both as a person and social construct/contemporary woman, in order to reconstruct, reshape or recolour parts of my own story.”

In addition to further exploring the depicted myths that summarise collections, she wants to continue experimenting with painterly interventions. In the future, she may cast her gaze on other periods. “I want to continue erasing and revising, and to keep using painting as a form of historical revisionism that questions the power of the image and symbolism of its participants.”

Inez de Brauw, Stroke Debate, 2025, Galerie Fontana