19 september 2025, Emily Van Driessen

Seeing That It Holds: Benoît Félix’ solo exhibition at Eva Steynen Gallery

In the stately townhouse of Eva Steynen Gallery in Antwerp unfolds Voir que ça tient, a solo exhibition by Benoît Félix. What strikes immediately is the play: within the works, between the works, and with the space itself. Drawings are hand-cut and suspended with delicate precision. A fly swatter, its mesh cut out of the frame, becomes Le rate-mouche and elicits a smile. A found, folded piece of zinc serves as a signpost, subtly pointing the way to another work. In the middle of the room, a piece bends into a new form: during installation, Benoît wedged it between the parquet floorboards. He plays with shapes, and with ways of seeing, reading and listening, letting the whole exhibition invitingly dance into being.

That playful shifting first emerged in the autumn of 2024, when an action faltered and a title announced itself. “I wanted to break a block of wood, but the wood resisted me; my movement stopped,” Benoît recalls. “Voir que ça tient flashed through my mind.” It became the first in a series of sculptures born precisely at the point where a material resists. “If I really wanted to create this form by breaking or splitting the wood, it is by no means certain I would succeed… I realised that at that very moment I was already making art without being aware of it.”

In Dutch, the title gains an additional layer: Zien dat het houdt. Here the word houdt (“to hold” or “to endure”) subtly overlaps with hout (“wood”). The pun cannot be directly translated into English, but for context: the title suggests both “seeing that it holds” and includes the very material that resists and reveals the form.

From that halted gesture to a precise handling: Benoît draws and cuts until only lines remain. His works often begin as drawings on tough, tear-proof paper, similar to the material of festival wristbands. He cuts away everything around the drawn lines until only the drawing itself remains: a trompe-l’œil that, at first glance, looks like knotted threads pinned to the wall.

Benoît Felix, Voir que ça tient, Eva Steynen Gallery

He himself sees links between his artistic practice and his earlier work in psychiatry: “I worked for fourteen years with children and adolescents with schizophrenia. They taught me that the boundaries between image, language and object (and body) are not self-evident for everyone. A reflection of light dancing on the floor could feel threatening. I personally know it’s just a visual effect, but that is not so immediately clear to everyone. They had to invent strategies to separate these different registers. And that idea influenced my work enormously, to play with those very boundaries. In this way, the story of a painting can become a sculpture, and vice versa.” That is why his titles do not function as labels but as part of the experience of these registers of language, object and image: they tilt perception. In U et Y pour tenir two lines shift into playful letters depending on the angle of view. Le poids de la transparence places a glass block on a hand photograph, so that weight becomes visible as pressure. In Voir un lien entre peinture et ceinture, one letter (p or c) is enough to set the eye searching where the leather belt ends and the painting begins. The whole in turn becomes an object again.

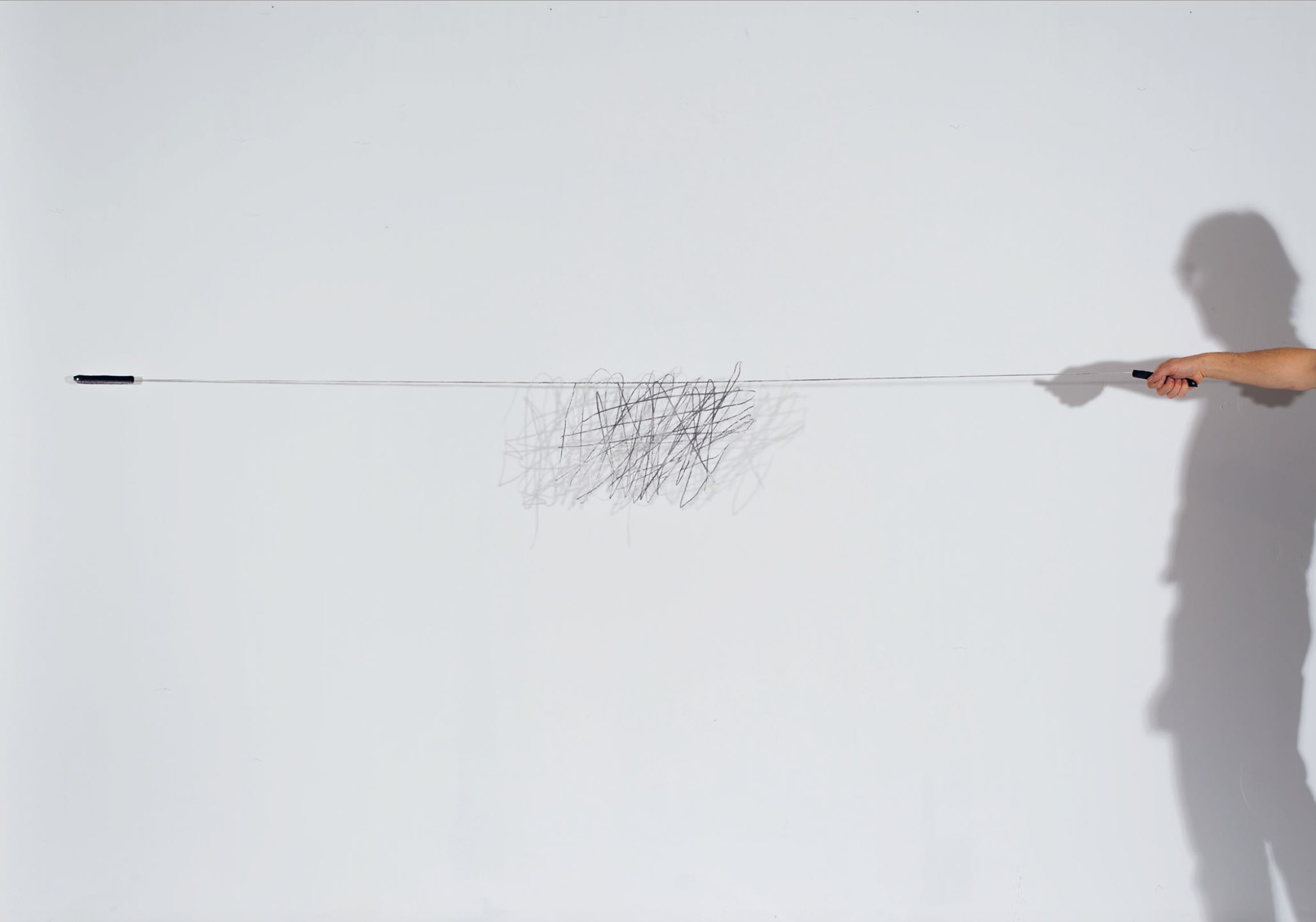

Sometimes this directing even shifts to the ear. In Soudain, la substitution du lisible au visible (un A pour écouter si c’est vrai) one immediately recognises the letter “A” in the object, but when Benoît shakes it back and forth we do not hear “aaa” but instead an intriguing “i-i-i:” the readable letter slides into an audible misreading, suddenly opening up all registers of reading, writing and listening. Rature pour deux hangs a crossing-out, a “mistake”, on the wall, with handles on either side to grab and walk around with: a subtle wink that mistakes are something we carry together. In Deux “T” pour croire que vraiment c’est un élastique he stretches paper to the very limit of the material, while the title subtly challenges our gaze and the work itself.

Benoît Felix, Voir que ça tient [see that it holds], Eva Steynen Gallery

Where perception shifts, so too does the idea that mistakes are wrong or unfortunate. In Les blessures sont les réparations (filet à regard) he marks small stumbles in his cut-outs as wounds in red. The net catches the gaze precisely where the making has “failed.” “I don’t like failing,” he says, “but now those wounds become indications. Some people ask me: ‘why do you do all this by hand? Just use a machine? It goes so much faster and better.’ But then I think: a machine doesn’t make mistakes. And these failures have ultimately been the poetic birth of the work.”

His sober way of working is not only aesthetic but also logistically considered and ecologically consistent: simple materials and transport without fuss. “When I have exhibitions abroad, I travel by train. And I can take all my works in one big bag. No van needed, just a ticket, a bag, and two arms,” he laughs.

Benoît Felix, Voir que ça tient, Eva Steynen Gallery, Eva Steynen Gallery

At the end of my visit, one work stood out with a poem as its title. “My titles are very important, an integral part of my work,” Benoît says, “but they always arise only after the work is finished.” The title of this work reads: Au bout d’un trait de pinceau trempé dans le noir toujours voir la nuit laisser du blanc paraître, et des dents (In English: At the end of a brushstroke dipped in black, always to see how night lets the white appear, and teeth). At first I thought the work was enclosed in a glass vitrine. But up close it turned out to be pinned directly to the wall. It was astonishing how, for a moment, it seemed as if the black paint was breaking through a glass casing. I could not turn my gaze away.

“It fascinates me when a work sets something in motion for the viewer,” Benoît replies when I share my thought experiment. “For me, art is a relational, social object,” he continues. “The artist gives, but also receives; sometimes the viewer knows something I don’t know yet. I know something, but never everything. The artwork is bigger than the artist; the artist is le petit.”

And through that imaginary “glass box” between maker and viewer perhaps emerges the very core of Voir que ça tient: the work holds because we carry it together, in dialogue.