19 august 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Adriaan Rees

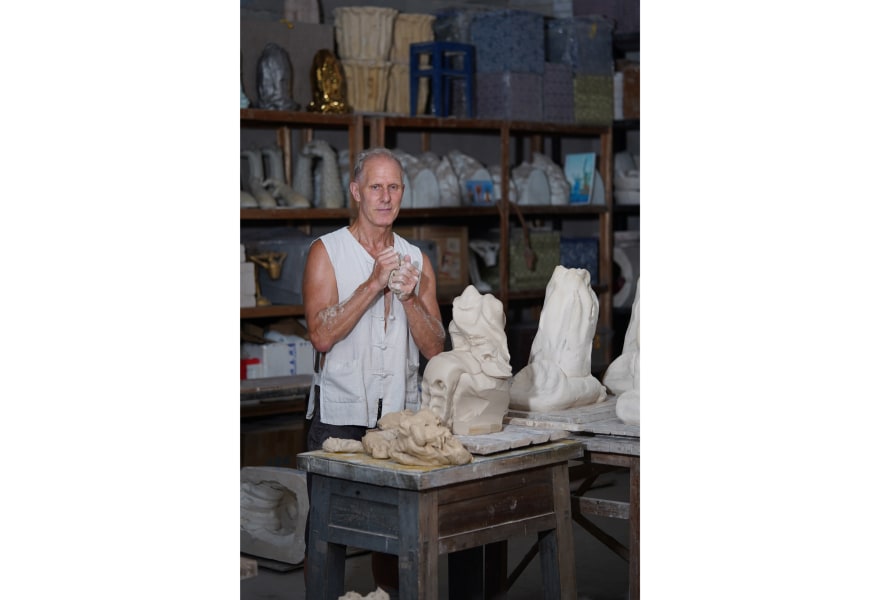

For almost 20 years now, sculptor Adriaan Rees has had a studio in the porcelain capital of the world: Jingdezhen, China. The material was invented there a thousand years ago and the city continues to revolve around porcelain to this very day. Rees ended up there by chance following a residency in China. He fell in love with the country, its endless possibilities and energy, and he never wanted to be anywhere else again.

In China, Rees discovered the value of dependency. In the West, we tend to do as much as possible personally, but in China, as Rees learned, people love to collaborate. He refers to his sculptures as Gesamtskulpturen.

At the sculpture garden of the Hague-based Livingstone Gallery, the installation Strange Fruit is now on display. Porcelain torsos hang lifelessly from ropes. Although Rees’ work does not normally address current events, he feels the need to speak out. “It is an indictment of today’s madness in which a human life is worth nothing and people prefer to look away rather than take real action.”

Strange Fruit by Adriaan Rees can be seen at Livingstone Gallery, The Hague, until 22 February 2026.

You were educated as a sculptor and work using various materials and media. In addition to a studio in Amsterdam, you also have a studio in Jingdezhen, China, the porcelain capital of the world. Can you tell us a bit about the city and your studio? What does it look like?

I first came to China 25 years ago when I was invited to do an Artist in Residence in Foshan, not far from Hong Kong. After my residency, I travelled across China for a month and more or less stumbled on Jingdezhen by chance. I had never heard of it and had no idea it would forever influence my life and work. It was a small city at the time with hardly any traffic and only much later did I realise how special it really is.

More than a thousand years ago, porcelain was invented here and the most remarkable thing is that so much of life in the city still revolves around this material. Thousands of students and thousands of craftsmen work with it—rooted in tradition, but also experimenting with the modern techniques and possibilities. I have witnessed it all and become part of it and it’s fascinating.

I fell in love with the country, its endless possibilities and energy, and I never wanted to be anywhere else. China became my motherland, but the Netherlands remains my fatherland. Since 2006, I have had my own studio at a large factory site called the Sculpture Factory. I was the first foreigner to start a studio there, which got me noticed, also by the officials of Jingdezhen municipality.

Tell us, what happened?

Soon I was asked by the municipality of Jingdezhen to set up an exchange between a city in the Netherlands and Jingdezhen. Although I had never been there before, I thought it had to be Delft because of Delft Blue, which once began as a poor imitation of Jingdezhen’s blue-and-white porcelain, but later grew into a brand name with its own identity. It wasn’t until 2007 that I managed to convince the mayor of Delft to visit Jingdezhen. After he had spent a day in the city, I was given the opportunity by the municipality of Delft to set up an exchange programme with the city of Delft, Royal Delft and Museum Prinsenhof Delft. This project lasted from 2007 until 2019 and produced enormous results.

Het duurde tot 2007 voordat ik de burgemeester van Delft zover kreeg om Jingdezhen te bezoeken. Nadat hij een dag in deze stad was geweest, kreeg ik de kans van de gemeente Delft om een uitwisselingsprogramma op te zetten voor zowel de stad Delft, Royal Delft als voor Museum Prinsenhof Delft. Dit project duurde uiteindelijk van 2007 tot en met 2019 en leverde enorm veel op.

Every year, I organised exchanges for artists and designers from the Netherlands and China, curated large exhibitions at various museums and worked closely with the Dutch Embassy. Meanwhile, I spent at least half of each year in China, steadily working in my own studio on my own projects. I experimented with the material and worked closely with countless craftsmen. All these artisans, many who boast incredible techniques and knowledge, are for me an inexhaustible source of inspiration, an extension of myself. And all of it mostly by trial and error, not being afraid to make mistakes and learning to embrace mistakes. And learning to throw away. What doesn’t work shouldn’t be endlessly kept: better to smash it and move on. The next sculpture will simply be better.

Meanwhile, the city has grown enormously and changes every year, becoming ever busier. Still, I don’t want to leave. I love the energy and the constant sense of the unexpected waiting around every corner. The Netherlands, or perhaps Europe, often feels to me like a museum of antiquities where preservation is the main concern and everyone is stuck in their own narrative.

What kind of studio space do you need for your work?

My studio in Jingdezhen is old, the windows are broken and the roof leaks. In summer, it is scorching hot and in winter, bitterly cold. It’s not big, about 70 square metres. The space is filled with moulds, sculptures, a few tables and hand tools. I prefer to work with my hands and as few tools as possible, but there are many things I simply can’t do and certainly not alone. Above all, I need people to help me. I am completely dependent on them and I like that. In the West, we always learn to be independent, but here I learned above all to be dependent. Someone has to order my clay. When I’ve made a sculpture, a mould maker has to create a plaster mould. A craftsman has to press the sculpture into the mould for me. Then my handiwork comes in again because I finish it myself. After that, it has to dry for weeks. If I want to glaze or paint it, there are people who make the glaze, people who can paint with countless techniques what I want. All under my supervision and from my idea, of course, but still. Lots of different people contribute to each part of the work and I consider it a Gesamtskulptur. Where possible, I glaze or paint personally, but where I simply lack the knowledge or technique, others do it. It's always a matter of give and take. Often people then go their own way. Sometimes it does not turn out well (and you throw it away), sometimes better than I ever thought possible and then the work rises above itself. All these people are just around, each with their own studio, around the corner or a few streets away.

Torso (Willem van Oranje), 2014, Livingstone Gallery

Suppose I were to do an internship with you. What would a typical day in your studio in China look like?

Haha, getting up early and working all day. But I always eat at the same time, at 12 and 6 o’clock, just like in the Netherlands.

Has the environment influenced your work? In other words, is there something you’ve learned in Jingdezhen that you couldn’t learn in the West?

Definitely. I like to travel, but only for my work. Ordinary holidays don’t interest me much. It is because the environment and people influence my work that I do this. Otherwise, I might as well stay at home. Besides, Jingdezhen is unique. There are thousands of things you can’t learn anywhere but here. I’ve been to lots places in the world connected to ceramics, but the possibilities here are truly much greater. And it still keeps changing and growing, while in many places it’s the opposite.

At Livingstone’s sculpture garden, Strange Fruit is on display until February 2026. It is an installation whose title refers to the jazz standard by Billie Holiday about the lynchings of Black Americans in the southern U.S. What inspired the idea for this installation?

As so often, it was a chain of circumstances. I have worked for years with Jeroen Dijkstra and his gallery. My work is often physical. In several installations, I had used torsos, presented in various ways. I found the gnarled tree in the gallery’s garden beautiful, even dramatic. By hanging three white torsos upside down from ropes in the tree, the image of a lynching naturally arose. Jeroen then came up with the title and it’s very poignant!

I have now expanded the installation many times over by also placing white, partly transparent glass sculptures in other parts of the garden. Here, I make reference to a battlefield, where body parts are still visible everywhere, marked by white crosses. It is an indictment of today’s madness in which a human life is worth nothing and people prefer to look away rather than actually intervene.

Because my work almost never deals with current events, I called on my alter ego here: Eduarda Seer. The installation will change several times over the coming half year. It is an experiment, of which I know roughly where it will go, but not exactly. That is exactly what I am looking for as an artist at the moment—it may also fail and then I’ll just smash it.

Adriaan Rees, Strange Fruit, 2019, Livingstone Gallery

You have made lots of work for public spaces in the Netherlands. Is there a place where you would still like to install a piece?

Yes, absolutely, in Rotterdam, because there is so much going on in that city, in many respects. Also, because there are so many different population groups!

What are you working on right now?

At the moment, I am in China making sculptures that most resemble unsightly lumps of soft flesh. Or something like that. In recent years, I have been mainly focusing on performances. But that’s another story altogether.

Adriaan Rees, The Killing Fields (detail), 2025, Livingstone Gallery