15 may 2025, Emily Van Driessen

Welt am Draht: A Tapestry of Meanings

As the walls gently creak with each floor passed, a tangle of voices, languages and sounds thunders from the speakers. German, Italian, English, indistinguishably mixed, like a feverish dream sequence. I am still in the lift, yet long before reaching the top, I had already stepped into 'Welt am Draht'.

The exhibition 'Welt am Draht', curated by artist Antoine Waterkeyn at Fred&Ferry Gallery in Antwerp, poses the question: was there ever a stage before there was an audience? "Of course, that is an absurd question," Antoine says. "Because without an audience, there is no theatre. There is only everyday life."

The exhibition title is borrowed from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1973 film Welt am Draht, in which a supercomputer contains a simulated reality populated by thousands of units who believe they are real people. "At one point, one of those units escapes," Antoine explains. "And then it confronts the lead scientist. ‘Don’t you realise that you might be a unit as well?’ Everything flips. The viewer becomes part of the system. Or perhaps they always were."

Sound as dramaturgy

The exhibition begins with an audio installation in the lift. Antoine weaves together excerpts from Welt am Draht with scenes from Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965) and Joseph Sargent’s Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970). All three films explore what happens when systems begin to override human agency. The soundscape is non-linear, filled with glitches, reversals and ambiguous repetitions. "Sometimes you hear a scene in which someone dies, and a moment later, there is a sex scene. At the end, I added a Wagner opera, just to extend the drama to the extreme," Antoine laughs.

Sound seems to operate as a second dramaturgy. "What interested me," says Antoine, "is that all these films begin from the idea that everything is a system, which ultimately turns against itself. And that the boundary between performer and audience becomes unclear."

Painting as writing

Antoine invited ten artists to participate. All of them share an affinity for the intersection between theatre, text and image. Many studied in Germany or Switzerland and, as Antoine puts it, have a “German connection”. "But the connection is not only biographical. It is a kind of attitude. A way of thinking that is performative, but does not perform."

Antoine Waterkeyn considers his painting practice as a way to visualise knowledge. His works often stem from literary or historical sources. "I create something like a Eurovision song for intellectuals, trying to transmit images without being didactic. It is my naive attempt ‘to educate’ the philistines." The figures in his paintings, hybrid and layered, are composed of parts from various origins: film stills, references to religious iconography, cultural archetypes. Each painting is a composition of fragments that enter into dialogue with other figures or canvases within the same series. "It is important to me that these figures are also in relation to one another." The paintings are spread across different rooms, yet together they form a coherent whole. "To me, painting is a form of writing. Each work is a scene, a building block in a larger narrative."

Antoine Waterkeyn, Sapristi, Sorcellerie et saint Sacrilège #1 (the king's vassal), 2024, FRED&FERRY

Rich metaphors and interwoven symbolism

One of the central series in the exhibition is based on La Cour des Miracles, a term used by Victor Hugo to describe urban areas where beggars, sex workers, Roma communities and other marginalised groups coexisted. These were places that escaped control. "These neighbourhoods really existed," Antoine says. "They were all called Cours des Miracles because supposedly the blind could suddenly see again and the lame could walk. But it was fake. They were performances. Even the bravest knights didn’t dare enter after dark."

He shows a painting in which Clopin Trouillefou appears, the jester from Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (1831). "He is the main rascal. A kind of king, also a fool. I built him out of pieces from other figures. For example, the devil from The Master and Margarita (1967) by Mikhail Bulgakov. Because Clopin is also a kind of master figure, but one that operates in the margins."

Below him, other characters appear: a drunkard, a mutilated knight, a Roma king. "For the mutilated knight, I used a still of Orson Welles as Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight (1965). He has something tragic, something overripe. For the Roma king, I searched for a kind of fakir, someone with a magical quality. That’s also how they are described in the book."

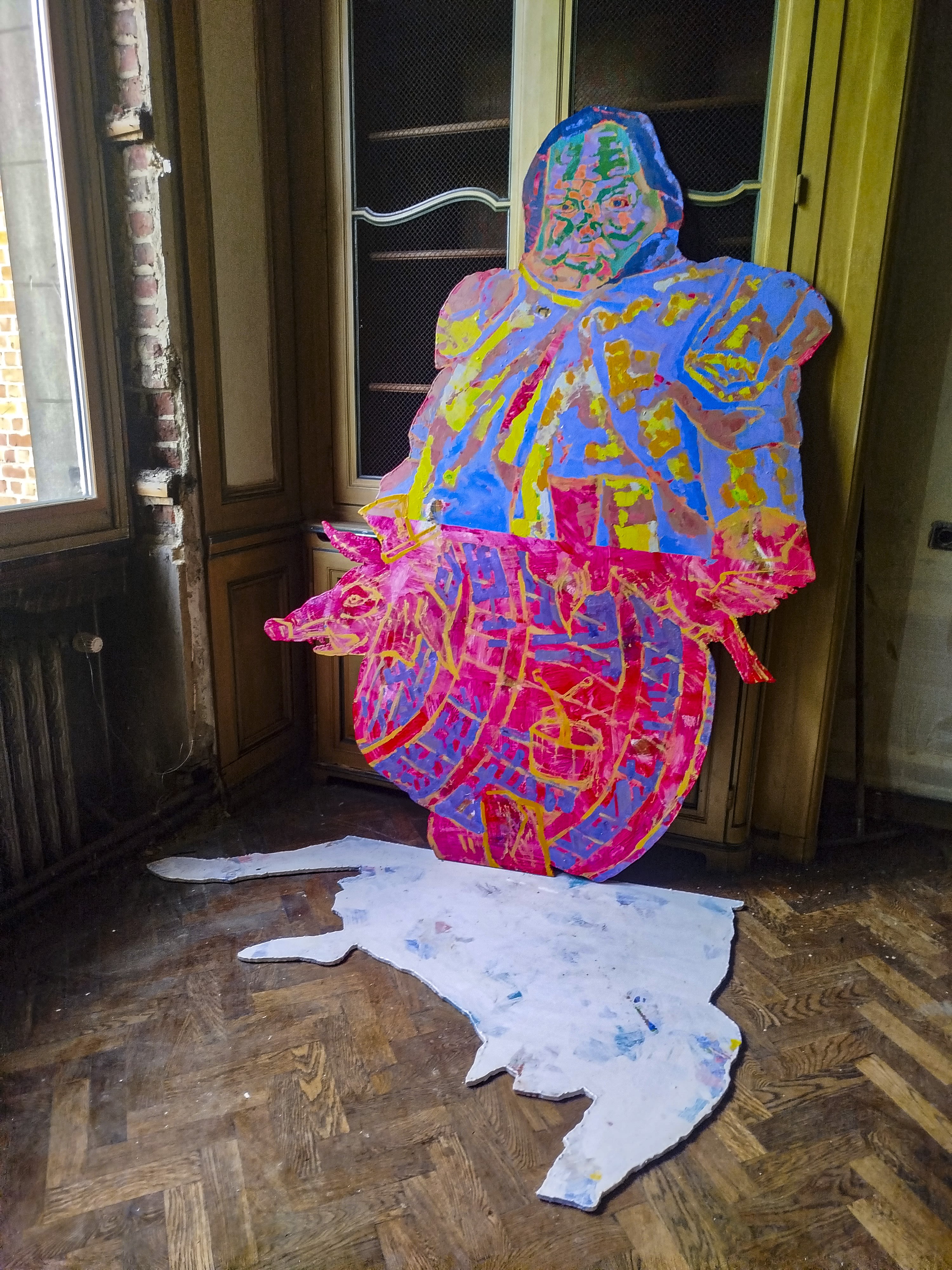

Antoine Waterkeyn, Sapristi, Sorcellerie et saint Sacrilège #3 (Orson & pig), 2025, FRED&FERRY

The figures are painted in fragments, each part constructed from a different visual register. "That has to do with their ontology. I want to show where these figures come from—their culture, their origins, their rhetoric. But it does not need to be literal."

Antoine points to a painting where a pig sits inside a wine barrel. "That is Gula, gluttony. And over there, Avaris, the frog, the miser. He carries his mattress on his back because he has no home. I added Mondrian colours to make the grid visible."

Heart of a Dog (1925) by Mikhail Bulgakov is also interwoven into the series. "That story is about a dog that receives the heart and brain of a criminal. He transforms into a kind of man, but also a monster. The professor in the book had to perform surgery between his books, because there was no space left. Bulgakov wrote it as a critique of communism, a system that equalises everything, but also flattens it."

In one of the paintings, Antoine depicts both the dog and the professor. "The professor is based on my old art history teacher. And at the bottom, I added Der Golem, from the German expressionist film Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (1920) by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese. That too was a mythical creature, created by a professor."

A moment later, he refers to another literary link: The Call of the Wild (1903) by Jack London. "A dog from a bourgeois family is stolen and forced to become a sled dog. Then comes the law of club and fang. They beat him to tame him. But eventually he becomes a wolf and joins a pack." All three stories explore forced transformation within a system that tries to control what is essentially uncontrollable.

Antoine Waterkeyn, Sapristi, Sorcellerie et saint Sacrilège #2 (dog), 2024, FRED&FERRY

The space as depot: the grey zone

In one of his painting installations, Antoine aims to break the tripartite division. The chair is not a coincidental element but refers to another part of his conceptually performative practice: the space as depot. "I try to create a theatre depot. A storage of fragments that escape their own narrative and function as props for a potential theatre piece. Not after the piece, when they already serve a function. I’m drawn to the moment before the explosion, the moment before the play begins. That moment holds far more potential." Certain elements function within that logic: a ladder, a chair, a blanket. "They are not audience, not set, not prop. They are just there to fill the void. I call them grey zones."

The work of Suchan Kinoshita aligns effortlessly with Antoine’s idea of the depot. "Suchan worked for years in experimental theatre in Cologne," he explains. "She never studied art, so her way of thinking starts from a different place."

Suchan Kinoshita, stick empathy, 2018, FRED&FERRY

In the downstairs space, a single work by Kinoshita stands alone: Stick Empathy (2019), a large stick balanced horizontally on a microphone stand. "That stick is an homage to her dog," Antoine says. "He used to fetch sticks, first small ones, then bigger and bigger. After he died, she found this beautiful, large branch. This work is the memory of him."

It is actually a performance piece. "You place that stick in your mouth, like a dog would, and then everything shifts. Suddenly you can’t pass through a doorway. Your relationship to the space changes entirely. But not everyone is allowed to perform it. Only those who are ‘chosen’." He points to two small notches in the wood. "That’s where your teeth go."

On the upper floor, a second work by Kinoshita can be found: PLATZhalter (2018), a small stepladder covered in fragments of Serbian carpet, applied segment by segment, one on each step. "It’s actually a cat tree," Antoine says. "And moths have eaten into it. You can still see the traces," he grins. "That’s such a grey zone. Not decor, not furniture, not a stage. And yet it fills the space."

Suchan Kinoshita, PLATZhalter, 2025, FRED&FERRY

Love, fate and death as performative elements

With Frank JMA Castelyn’s work, the connection to Antoine’s depot thinking is immediately clear. On the ground floor stands Point of Intersection (2019), a piece made with two ladders crossing each other, bearing the words amor fati in neon. Amor fati literally means love of fate. Antoine draws a conceptual link with Nietzsche, who saw it not just as accepting one’s fate, but as saying a full and conscious yes to it, even to what is painful, difficult, or incomprehensible.

That idea returns in his view on art and curating. "I do not believe in works that need explaining. Everything nowadays is too labelled, too easy to digest. Hamburger art. I want people to start thinking for themselves. That meanings are still in flux. That it is about a shared abstract energy, not some pseudo-spiritual whole."

Frank JMA Castelyns, Point of intersection, 2019, FRED&FERRY

On the top floor, a second work by Castelyn can be found: ILLUSION ZUM TODE (2025), a light piece in which a different part of the text becomes visible depending on your position. Antoine makes a link with ICH–DU (1979) by Bernd Lohaus, a monumental concrete installation in which the words ICH and DU are carved on opposite sides. Depending on where you stand in the space, you only ever see one. Never both at once. The work shows how subject and other can never fully coincide.

That same tension appears in ILLUSION ZUM TODE, where you can only read one part of the light text at a time. The work refers directly to Heidegger’s Sein zum Tode, a concept that understands human existence through its relation to death. The awareness of mortality gives real weight to choice. Castelyn takes that further. ILLUSION ZUM TODE does not present a clear awareness, but a state of projection. Life still moves towards death, but in a mist of projections. "Everything you see comes from within yourself," Antoine says. "When you are in love, you see someone entirely different from the one seen by the person standing next to you.”

A tapestry of meanings

There are many other fascinating works to discover in this exhibition. 'Welt am Draht' is a tapestry of meanings. Each work stands on its own, but gains depth through its relation to what surrounds it. There is no fixed plot, yet certain images and ideas keep returning, shifting, reinforcing one another. As a visitor, you are invited to search, hesitate, and begin again.

What I admire is how Antoine brings everything together in a structure that feels both precise and open. 'Welt am Draht' is an exhibition that resonates from the moment you enter the lift to well beyond your exit from the gallery space.