13 april 2025, Martine Bontjes

The studio of… Müge Yilmaz

On the edge of Amsterdam, in the Tuinen van West, lies the studio of Müge Yilmaz. In this creative hub, the Turkish artist works from a south facing attic, surrounded by artists, architects, and designers. Her day begins with a calming ritual: filling a large teapot, refreshing her dog's water bowl, and then watering her plants — ready for the real work. From here, she continues to develop her installations, sculptures, and performances, which feel both archaic and futuristic. Her search for her ancestors led Yilmaz to the discovery that the answers she sought were already hidden in her own roots.

For her solo exhibition 'Anatolian Goddesses' at GoMulan Gallery in Amsterdam, Yilmaz explored prehistoric goddess worship and the traces it left in our contemporary culture. Her work speculates about lost artifacts and matriarchal societies. She reveals how patriarchal systems erased female symbolism: “Architecture, agriculture, art – all these fields have been offered to us as if they have been invented by men but I don’t think so. ” She combined historical research with her own fieldwork in Anatolia, the Asian peninsula of Turkey. With her work, she brings the strength and presence of Neolithic women back to the present.

Join the artist this upcoming Saturday 19 April from 5:30 to 6:30 pm for the finissage, as she discusses the process behind her exhibition with art critic Nesli Gül.

Where is your studio, and what does it look like?

My studio is located in Nieuw West in the Tuinen van West area. It is part of a broedplaats called 1800 Roeden with many other artists, architects and designers. It is right in the edge of Amsterdam, in a green area. Mine is a second floor atelier with attic windows luckily facing south.

Take us to one of your studio days, how do you start your day? Do you have certain routines that help you get going?

As soon as I enter the studio I ring the bells that are hanging from a mais root next to the entrance to announce my presence. Then I take care of the waters: I make exactly 1 liter of tea, I give water to my dog if she came with me on that day, I give water to the plants. Then, if I am going to make dirty work, then I change my clothes.

Do you think your interest in history has roots in your childhood? Or did you develop this interest later in your career?

I like that the words history and roots are next to each other in your question. In a way that gives way to answer, I have always been interested in the roots of this, the roots of art, the roots of painting, the roots of agriculture by which I mean its beginning. The beginning of belief for example is really interesting to me. So I have always been interested in history and the origins of things, but going towards my own roots and ancestors came later. It was an epiphany-like experience where I understood everything I was looking for was right in front of me and in my own roots.

Can you tell us something about your research for your exhibition at GoMulan Gallery, what sources did you consult?

The biggest source was one book The Goddess from Anatolia written by James Mellart, Udo Hirsch and Belkis Balpinar. This is a very rare book that I had been looking for for years and recently I was lucky enough to find a full copy. This book speculates, through images and text, a continuous line between neolithic goddess cults and contemporary patterns on kilim designs. This to me is obvious somehow, I know in my heart that is true however this book and its writers were harshly criticised because they were speculating a bit too much for the academic world. Its story is very similar to the life of Marija Gimbutas, whom I also read and who inspires my work greatly. She was a Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist and wrote a book called The Living Goddess. This book inspired my other installation called "Goddess Theory" immensely. Unlike the writers of the other book, who were using drawing to speculate on goddesses, Gimbutas was doing field research and was finding actual goddess figurines made of clay however she was also dismissed largely by the academic world due to misogyny.

Also my real life experience of traveling to the actual archeological areas such as Çatalhöyük and Göbeklitepe was illuminating. These are neolithic archeological sites in the South and South-East part of my current homeland, thus Anatolia whose lower part is also named Mesopotamia. James Mellaart, who wrote the book mentioned above was one of the first excavators of Çatalhöyük which remains one of the first human settlements in the shape of a city constructed 7000 years ago. Göbeklitepe is older and is more towards the East side, it was inhabited from 9500 BCE and on. This is an incredibly abstract artistic architecture made of stone pillars that contain mysterious shapes together with sculptural depictions of animals such as wild boar, vultures, snakes and human figures. It is now believed that it was connected to the beginning of agriculture and to the beginning of belief.

If you read contemporary history books, they always mention how the discovery of Göbeklitepe changed everything and our perception of history. It is controversial also because it hints at a matriarchal society. I always try to recreate in my work the feelings I had when I went to visit this site. So with my work, I am also speculating on the lost art works and artefacts of history. Coming closer to our contemporary world, the bible clearly mentions how the Asherah poles were intentionally destroyed by the Jesuits as a form of oppression. They were artworks dedicated to the fertility goddess Asherah, also known as Astarte or Asherim. She was the last standing goddess and was violently destroyed by patriarchal belief systems and this happened only 2000 years ago. (Exodus 34:13 states: "Break down their altars, smash their sacred stones and cut down their Asherim [Asherah poles].")

Are the goddesses Ishtar, Tomris, Umay and Cybele also celebrated in Turkey? Or is the existence of this matriarchy only recently discovered?

They are and they are not. The country as it is today, remains a very patriarchal place. These goddesses however leave their traces in women’s names today, for example my aunt is called Sibel which is a derivation of Cybele, Tomris used to be a common name and when I was a teenager there was a singer called Umay Umay which is now my little sister’s name. So there is a continuous thread. I also expect a return of the goddess in the country’s culture in general as a radical political resource. Umay for example is still known as a pre-religious turkic goddess that was the protectress of pregnant women and their babies. She is really the top goddess in this realm. The root word umāy means placenta, womb or uterus. She is also connected to the first shamans which were women. What is special about her is that she is venerated in the larger turkic world, so whole central Asia such as Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. We see this in a recent song called Homay that became extremely popular by the Bashkir band Ay Yola.

Cybele is a similar goddess more related to agriculture. She has many varying depictions from neolithic to greek mythology where she mostly like turns into Demeter as goddess of harvest. She is a goddess sitting on a throne, with lions and sometimes is depicted with many breasts. You can see her 3D printed in other works too. Archeologists speculate that her many breasts turn into grains such as wheat. Her figurines were found in grain storages in the beginning of agriculture.

Working with digital technique like 3D printing connected your ancient references is very innovative. Is this tension between ancient and contemporary is something you play with more often?

Yes I always tried to do so. My frame of reference is 10.000 years ago and 10.000 into the future. When these archaeological artefacts were made, maybe they were the newest technology of their time. Firing clay in high temperatures was ground-breaking technology in the neolithic. I believe right now 3D printing in metal is a similar method and I constantly think of what is yet to be invented. By using the current technologies I also try to imagine the future goddesses, the ones that are yet to come.

Your work seems to restore the presence of women in prehistory. Do you see your practice as a form of resistance?

Absolutely. I look at everything from a feminist lens and reinsert women wherever they have been erased by the patriarchal pen. Architecture, agriculture, art all these fields have been offered to us as if they have been invented by men but I don’t think so.

The figure in "Mother of My Mother" seems to have quite some authority. What does her position symbolize for you in relation to her role as a mother goddess?

She really is the oldest ancestor in the exhibition indeed. She is sitting on her throne, surrounded by two lions. She definitely is some sort of authority that has been generated by years of experience and she quite figuratively looks like my own mother and my grandmother who passed away recently.

The pose of "Umay The Progenitrix" feels slightly more open or generative—was that intentional to reflect Umay’s nurturing qualities?

Yes, very accurate observation as "Umat the Progenitrix" indeed represents the future in this context and from my perspective. She is yet to become. Next to the archeological and neolithic references, she comes from the other side of the coin from what hasn’t happened yet. She is influenced by reading Octavia E. Butler, especially her book Dawn. She could be a goddess from space, from another realm, maybe not human, maybe half human half tree, maybe an alien woman. She is open and still has many possibilities and many tentacles. She has an inner space that is just potential.

What could your Amazon figures teach us about the way we look at contemporary women?

They tell us about the fact that we are really much stronger than what we think.

What are you working on at the moment?

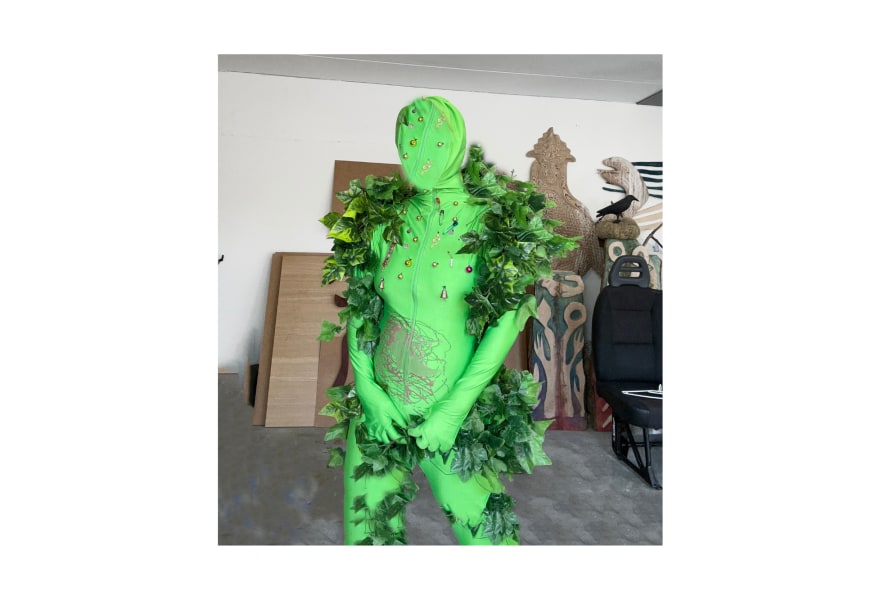

At the moment I am focusing on two important projects: one is a group exhibition that will open in July in Amsterdam. I am commissioned a new installation that will talk about the phenomena of naturalisation both of people and of plants. I will be making a personal work for the very first time. Then together with the collective that I am part of, 4Siblings, we are developing a new plot on a piece of land in Sloterplas, Amsterdam. We will remediate the soil and develop land art and food sovereignty projects on it. This year’s theme is called Decompositions and the harvest is expected in late September this year. You are very welcome to join!