11 march 2025, Flor Linckens

Animals and human beings in SmithDavidson Gallery: an age-old dialogue

Until 1 June, SmithDavidson Gallery in Amsterdam presents 'Le Carnaval des Animaux', a group exhibition exploring the layered and timeless relationship between human beings and animals. This exhibition aligns with a long-standing tradition in art history, where animals have served as a source of artistic inspiration for centuries. Bringing together various artists, the show examines the presence and significance of animals in art from multiple perspectives. These depictions raise questions about identity, connection and the way we perceive nature. Alongside photography and works on paper, the exhibition also features paintings by Australian First Nations artists, introducing additional depth to the presentation. Among the participating artists are Marie Cecile Thijs, Ingo Arndt, Marc Lagrange, Vincent Lagrange, Jorna Nelson Napurrula, and Matthijs Scholten.

For centuries, animals have played a crucial role in art history. In stately Renaissance portraits parrots often appear as status symbols, while lions have symbolised power and courage on coats of arms. Mythological and religious depictions often feature animals as messengers, divine manifestations or metaphors for human traits. At times, they embody power, wisdom or vulnerability. In other works, they serve as abstract representations of instinct, or primordial forms. In battle scenes, horses and elephants stand as silent witnesses to history. In other pieces they become political metaphors, as seen in Animal Farm. Some artists anthropomorphise animals, using them as reflections of human emotions and social structures, while others present them as autonomous beings with their own perspectives, independent of human perception. The exhibition at SmithDavidson Gallery brings together a diverse range of viewpoints, from anthropomorphic portraits and mythical transformations to critical reflections on the complex relationship between human beings and animals.

Marie Cecile Thijs’ work evokes the atmosphere of 17th-century Dutch masters, yet with a distinctly contemporary approach. In her highly stylised compositions, the Dutch photographer freezes time, removing animals and objects from their familiar contexts to imbue them with an almost mythical quality. A cat wearing a digitally added ruff, sourced from an authentic 17th-century piece in the Rijksmuseum’s collection, gazes at the world with regal solemnity. Elsewhere, two pigeons balance atop a globe, and in another image, two snails crawl across the face of a clock, as if time itself takes on a different meaning. In her compositions, animals are elevated to near-mythological status, while maintaining their tangible, everyday reality.

German photographer Ingo Arndt captures the world of wild animals with unparalleled precision and sensitivity, portraying them not just as subjects of observation but as autonomous beings within their own habitats. His award-winning work, featured in National Geographic and BBC Wildlife, is the result of months-long expeditions in which he fully immerses himself in nature. His images — such as the intense gaze of a puma in Patagonia or a bear standing upright in shallow water — reveal not only the physical power and beauty of these animals but also their unique presence within the landscape. Arndt’s photography transcends pure documentation, touching upon something timeless. His work raises awareness of the fragility of nature while preserving the majesty and untamed force of his subjects.

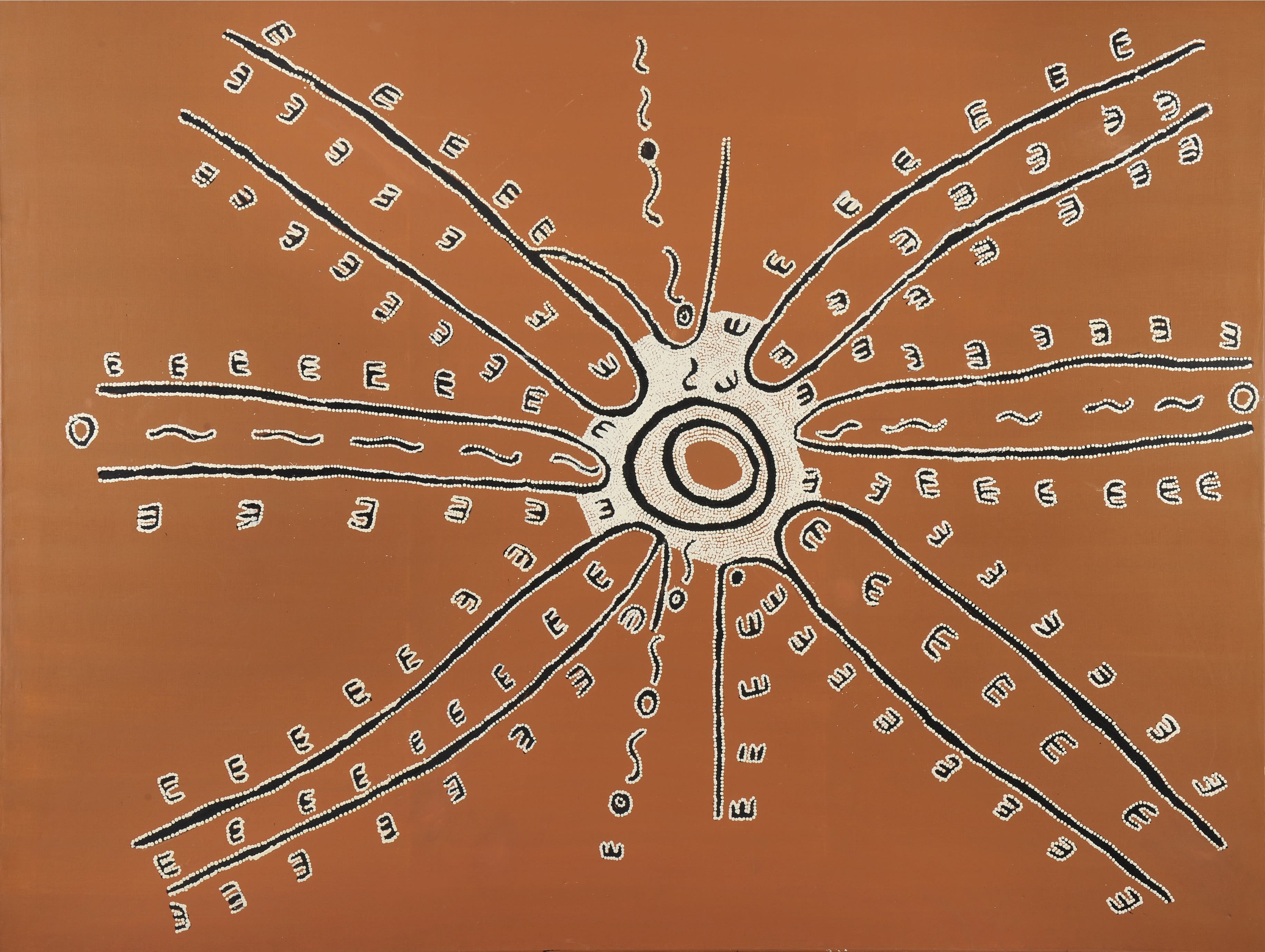

Jorna Nelson Napurrula’s painting "Janganpa (Possum) Dreaming" (2007) is deeply rooted in the Warlpiri tradition, where art is not just a form of visual expression but also a spiritual and historical archive. This piece traces the path of the janganpa, the brush-tailed possum that moves through the landscape at night, leaving behind trails represented by swirling lines and rhythmic ‘E’ shapes. Now extinct, the janganpa plays a central role in ancestral Dreaming stories that define the relationship between people, animals and land. Using an earthy colour palette and a distinctive technique, Napurrula brings to life a spiritual cartography that captures both the janganpa’s movement and the profound connection between the Warlpiri people and their land. In the exhibition at SmithDavidson Gallery, this work contrasts with the more figurative animal portraits, adding an abstract (from a Western perspective), meditative layer to the dialogue on the role of animals in art and culture.

Belgian photographer Vincent Lagrange portrays animals as if they were human: intimately, directly and with a sense of individuality. Rather than capturing them in motion within their natural environments, he presents them in stillness against neutral backgrounds, directing attention to their gaze, posture and texture. A rhinoceros with a fragile yet determined expression, a walrus peering pensively into the camera, a snowy owl with an enigmatic stare — his portraits challenge viewers to see animals not as ‘the other’ but as beings with their own presence. Through "The Human Animal Project", Lagrange explores the connection between human beings and animals, playing with the boundaries between recognition and alienation. His work subtly prompts the question: is the distance between us and other species really as vast as we assume? His photographs have been featured on the cover of National Geographic.

Matthijs Scholten paints as he thinks — impulsively, uninhibitedly and unfiltered. The Dutch artist’s work bursts with energy, blending influences of graffiti culture, outsider art and instinctive lines that defy convention. Bold colours and raw contours collide and merge, making his canvases almost vibrate with intensity. Animals appear as hybrid creatures — part instinct, part imagination — sometimes grotesque and distorted, sometimes dynamic and playful. In 'Le Carnaval des Animaux', his paintings provide a striking contrast to the more restrained or stylised animal imagery in the exhibition, serving as a reminder that animals in art need not always be refined or symbolic but can also be raw, unpredictable and wild.

Marc Lagrange approached photography with a near-cinematic sensibility, where every detail — composition, lighting, texture — was meticulously orchestrated. One of his iconic photographs features a nude woman hanging from an elephant’s tusk, her body taut while the animal appears to accept the situation. The image provokes questions about power and physical dominance, as well as the shifting dynamics between human beings and animals. Lagrange favoured analogue techniques such as platinum printing, a rare and labour-intensive process that enhances depth and softness in his images. In the context of this exhibition, his photography introduces a dramatic, almost theatrical dimension to the interplay between people and animals.