14 january 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Ruben Mols

Open any random desk drawer at home and chances are you'll find an old iPod or Discman. Once-coveted items that were treated with care. Nowadays, they sit gathering dust. But throwing them away feels like a step too far. Why is that?

Rotterdam-based artist Ruben Mols creates sculptures out of outdated consumer electronics and data storage devices. Mols has recreated things like keyboards, floppy disks and a Tamagotchi in slightly larger formats and considers these devices extensions of our identity. “In performing various cognitive tasks, we outsource such tasks to our electronics. This has created a circuit between the user and the device that influences how we connect with ourselves and others, how we receive information and what kind of world we live in. Our technology is formative and should be viewed as such.”

The exhibition 'Connected', featuring work by several artists including Ruben Mols, Pieter Martyn and Saminte Ekeland, can be seen at Frank Taal Gallery in Rotterdam until 8 February. On 16 February, a duo exhibition by Ruben Mols and Vladimir Potapov will be opening at the gallery.

Ruben, where is your studio and how would you describe it?

My studio is located at Kunst&Complex in Rotterdam, a rectangular space of 33 square metres with white walls, evenly lit by daylight lamps and with a set of windows on one side. You might describe it as a fairly sterile environment. The previous tenants were architects who worked to make the space very sleek and I’ve benefited considerably from that.

Ruben Mols, Compact Disc, 2024, Frank Taal Gallery

A painter swears by natural light, preferably from the north. That seems less critical for your work since you make sculptures from outdated consumer electronics, like old keyboards, CD jewel cases and floppy disks. What makes the perfect studio for you?

Since my work is quite varied, I try to keep the space flexible. I set up workstations with trestles and table tops as needed. I like being able to focus intensely on my work, so it never gets too messy—everything has its place. The location of my studio is also highly convenient. There is a hardware store within walking distance and a laser-cutting service only a block away. A convenient location isn’t a must, or always a choice, but it does save a lot of time.

Suppose I were to intern with you. What would the workday look like?

That depends on what stage the work process is in. It starts with a digital phase of composing images and drawing them on the computer. When it transitions to the physical phase, the work might involve a lot of sanding, priming and painting. The finishing touches on the sculptures take a lot of time. Sometimes, I need help with welding or creating 3D models. Other times, there’s assembly work to be done for kits or mould-making.

Congratulations on you participation in 'Connected' at Frank Taal Gallery! Which works will we see there?

In the exhibition 'Connected', I’m showing three works titled Intro-spec-tech (I, II, III). These were inspired by the realisation that my phone knows more about me than I know about my phone. To learn more about the device, I started dismantling my phone and other electronic devices. Inside, or ‘behind the screens’, I found an intriguing visual language—shapes, components, cutouts—all with functions I didn’t understand. I tried to make this visual language my own, resulting in work like the Intro-spec-tech series. After 'Connected', I’ll be exhibiting again at Frank Taal, showcasing, among other things, the Attic Memory series.

Ruben Mols, Attic Memory - Pilgrim, 2024, Frank Taal Gallery

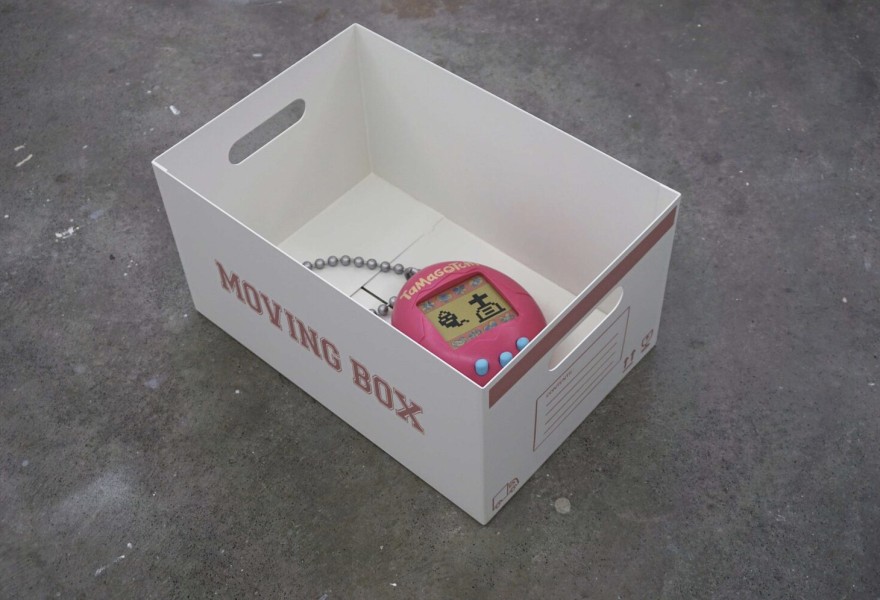

Your work touches on an underexplored theme: how devices and electronics influence our identity or self-image. Your latest series, Attic Memory (2024), consists of moving boxes filled with discarded electronics and data carriers like floppy disks, a Tamagotchi and a keyboard. These items are boxed up—we no longer use them but refuse to throw them away. Do you consider them ego documents or extensions of ourselves, and how would you describe that relationship?

Absolutely as extensions. In performing cognitive tasks, we outsource these tasks to our electronics. This has created an interwoven circuit between user and device, something I find incredibly fascinating. It influences how we connect with ourselves and others, how we process information and the world we live in. Our technology is formative and should be viewed as such.

In the Attic Memory series, I reflect on the digitisation of the ‘80s and ’90s, a period when much of what we now take for granted was in its infancy. Each device had its specific task and physical quality. Admittedly, LPs take up space and a Spotify account is much easier in that sense. But I still believe that putting on a record, listening to it and flipping it over adds something significant to the listening experience. The way we handle data now is far more intangible. In my work, I aim to express that physical loss.

Do you remember where your interest in the relationship between these consumer goods and our identity originated?

I think my interest in this contrast stemmed from the rise of social media platforms like Myspace and Hyves. The discrepancy between what was presented digitally and what was ‘real’ offline made me question things. The shaping of an online persona within the boundaries of digital architecture generates resistance for me. That resistance stems from my belief that human complexity cannot be captured, translated or represented by artificial structures. Growing up in the ’90s, with video games, Tamagotchis and computers, also influenced me early on.

Ruben Mols, Attic Memory: Out of Mind, 2024, Frank Taal Gallery

Which object was the hardest to produce?

The most complex was the Tamagotchi. I started by creating a 3D model on the computer, after which it was printed, sanded and painted. The screen consists of laser-cut acrylic and wood and the buttons are made of silicone. It was a dynamic production process involving computer-guided machines and traditional mould-making and casting.

The most labour-intensive task was to create the keyboard, which is based on a model from the brand Altrix. It has 106 individual keys, all of which had to be sanded at the right angle, primed, painted and engraved. I don’t mind repetitive work—I actually find it quite satisfying.

If money and time were no object, what kind of project would you work on?

I’d love to create a fictional factory setup, fully equipped with assembly stations and conveyor belts, where sculptures are assembled step by step. It would be a performance of speculative industrial production. My ideas for this project touch on automation, industrial scaling versus craftsmanship and manual labour. I’d also like to experiment with plastics, using injection moulding, for example.

Your work mainly focuses on data carriers from the ‘90s. Since then, we’ve transitioned from physical carriers to streaming and social media. Do you think you’ll create work about social media in the future?

I have a lot of ideas about the relationship between humans and machines—it’s something I think about a lot. In a way, my work already comments on social media indirectly. For instance, showcasing the Tamagotchi reflects on the addictive nature of social media and risks of online validation. We’ve become like Tamagotchis ourselves, constantly demanding attention and interaction. I hope my work offers reflection on the ongoing experiment of evolving technologies. I wouldn’t rule out making work that explicitly addresses social media in the future.

Ruben Mols, Intro-Spec-Tech III, 2020, Frank Taal Gallery

A new year has just begun. What’s on the agenda for 2025?

It promises to be an exciting year. 'Connected' at Frank Taal kicks things off. In February, I’ll be exhibiting there again, alongside Vladimir Potapov (opening 16 February). Also in February, I’ll be part of a duo exhibition with Valentino Russo at Kunsthal Kloof in Utrecht (opening 28 February). My work will be featured at Frank Taal during Art Rotterdam (28-30 March 2025 in Rotterdam Ahoy). Around that time, I’ll start creating a publication about the work made in 2024. There’s also a possibility that my work will be shown at an art fair in China through my collaboration with CHAxARTxRTM. I look forward to all of this and am curious about how my work will continue to develop.