18 january 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

De Gloeiige - Erik van Lieshout about his latest project, farmers' art and a towering rabbit

Undoubtedly, the most striking booth at Art Rotterdam will be that of the Annet Gelink Gallery. No one will be able to casually pass by a 3½-meter-high rabbit made of hay. For his new project, tentatively entitled De Gloeiige, Erik van Lieshout temporarily traded his residence and workspace in Rotterdam for his hometown of Deurne, an agricultural village on the Brabant side of the Peel that has become a focal point in the resistance against nitrogen policies in recent years. Van Lieshout spent a year there capturing footage for a new film, creating sculptures of eggs and the hay rabbit. Handmade T-shirts, crafted by Van Lieshout in collaboration with Rotterdam fashion designer Jeroen van Tuyl, are also available for purchase.

"Have you ever stood in a barn with a thousand pigs?" Erik van Lieshout asks somewhere in the middle of our conversation. There is a brief silence. "See, that's the point; the city and the countryside are two worlds that don't often interact." That is precisely what Van Lieshout aims to do with his project: bring these two worlds into contact with each other, even if it means causing a bit of friction.

Erik van Lieshout | Photo: Suzanne Weenink

De Gloeiige

Erik van Lieshout's latest project takes its working title from the regional myth of a ghostly apparition observed at night in marshes and marshy heathlands. In one version of the legend, the ghost is a farmer who had tampered with boundary markers. After their death, the spirits roam around, trying to reconcile before finding peace.

While De Gloeiige (which translates as ‘the glowing one’) closely follows political events, Van Lieshout has previously created works about farmer protests. The unruly demonstration in front of the Friesland provincial government building in 2019 was the subject of a large collage made from coloured vinyl, just like the tractor protests in The Hague the following year. Protests and challenging the status quo are recurring themes in Van Lieshout's work. This traces back in part to his upbringing in Deurne, where village politics have been traditionally dominated by the interests of pig and chicken farmers. Van Lieshout's parents were not farmers, making him an outsider and giving him a love-hate relationship with the local farmers.

Very positive

"It's a really hardcore industry and the farmers know that something has to change," Van Lieshout summarises the situation, "because we’re up to our ears in manure here." With the film he is currently editing, he hopes to bring about sustainable change in the region. Apart from farming, there is little to do in the Peel, according to Van Lieshout. "There are no bike paths, beautiful walking routes or coffee bars, and aside from the Wieger, no museums. I want to change and transform the area into something enjoyable." For this reason, Van Lieshout refers to his project as “very positive for farmers”. But this is not as straightforward as it may sound because the farmers were not initially open to an exchange with an artist. "Farmers tend to keep to themselves and nowadays, they are especially wary of the media and animal rights activists," says Van Lieshout. For De Gloeiige, it helped that he came from Deurne and spoke the language. Van Lieshout was transparent about his intentions – "they know I'm a left-wing activist" – and thus gained their trust. He gradually earned their trust and permission to film everywhere. What also helped is that, according to Van Lieshout, the region has a lot of humour. Despite the serious message, humour is not lacking in Van Lieshout's work or in the film. At the festive conclusion of the project the day after the parliamentary elections – one of the hay rabbits was to be burned while everyone enjoyed a bowl of pea soup and beer – everyone who contributed to the project from the neighbourhood showed up, much to Van Lieshout's surprise.

While occasional friction is only natural, it enhances the film. Van Lieshout welcomes collectors and museum delegations, bringing them into contact with the farmers. An uncomfortable gathering, not least because some urbanites are vegetarians. This underscores Van Lieshout's point that urbanites and farmers rarely encounter or know each other.

Vreugdevuur van het Hooikonijn, Deurne, 23 november 2023 | Photographer Suzanne Weenink

A towering rabbit

Van Lieshout not only addresses the separate worlds of the city and countryside, but also poses the questions of who owns the land and what can be done with it. He gained access to the ruins of a farmhouse, owned by a veterinarian who, like Van Lieshout, left the region to study. The veterinarian now wants to return to start a laboratory developing a serum for snakebites. This would involve testing on laboratory rabbits. The plan faces strong opposition, not only from activists, but also local farmers. In response, Van Lieshout decided to build a towering rabbit made of salvaged wood covered in hay on the veterinarian's land, a provocative imitation of the hay structures that farmers set up along the road in protest against nitrogen policies.

Another location that plays a prominent role in the film is the area behind the ruins: a vacant 250-hectare terrain. Originally intended for greenhouse development, the financial crisis of 2008-2013 prevented any progress. The development of this area is a hot topic in the municipality. Some residents want nothing to be done with it, while local farmers would prefer a manure fermentation factory, allowing everything to remain the same.

Photographer Suzanne Weenink

Farmers' art and T-shirts

The veterinarian allowed Van Lieshout to use everything he found in the ruins for his work. Planks, belts, pitchforks and spades were all incorporated into sculptures. But the main component is the white eggshells. Van Lieshout purchased the eggs from a local farmer. Using a needle, Van Lieshout pierced a hole and blew out the contents. He used the empty eggs in a series of sculptures that might be called farmers' art. The imagery refers to farm life and Catholicism – the comparison to a rosary is easily made with a chain of eggshells – two pillars that shaped and continue to shape life in the region. Some of these sculptures will be exhibited at Art Rotterdam at the Annet Gelink Gallery booth.

Jeroen van Tuyl | Fotograaf Suzanne Weenink

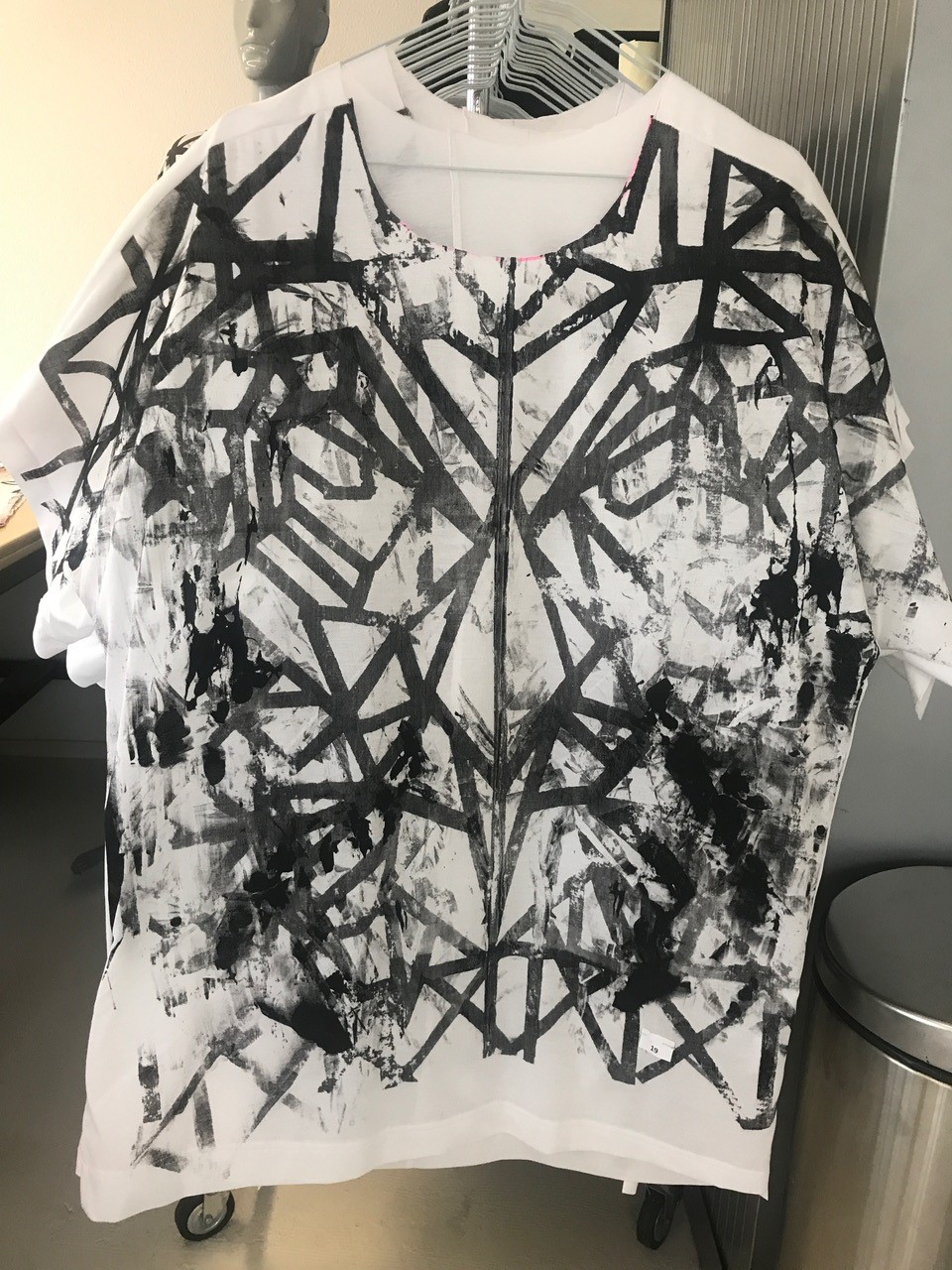

A self-made T-shirt is also available for purchase in a limited edition of 50, resulting from Van Lieshout's collaboration with Rotterdam fashion designer Jeroen van Tuyl. Van Lieshout used Van Tuyl's logo, a kind of mask, as inspiration for a sketch, which ended up as a Mondrian-like drawing with sleek vinyl lines. Van Lieshout and Van Tuyl screen-printed an enlarged version of it on white cotton. Each shirt has its own – often double – print in typical raw Van Lieshout style. Van Tuyl created the design. "Putting it together is meticulous work; the entire family has been involved and we’re still working on it," says Van Lieshout, who hopes to have the 50 shirts ready for Art Rotterdam.

The final film with the working title 'De Gloeïige' is made possible by the Noordbrabants Museum and the Mondriaan Fund