31 august 2023, Yves Joris

Sybren Vanoverberghe’s open-lens archaeology

In a previous interview with Sybren Vanoverberghe, he confided in me that he is fascinated by the traces left behind by humans. In his upcoming exhibition Desert Spirals, on display at Keteleer Gallery from 2 September through 7 October, he continues to explore this fascination.

For his second solo exhibition at Keteleer Gallery, the photographer-artist travelled to the Moroccan desert. Ancient engravings alternate with other traces from the past in a search for the 'nothingness' found in the desert. A fascinating quest that Sybren enjoys explaining.

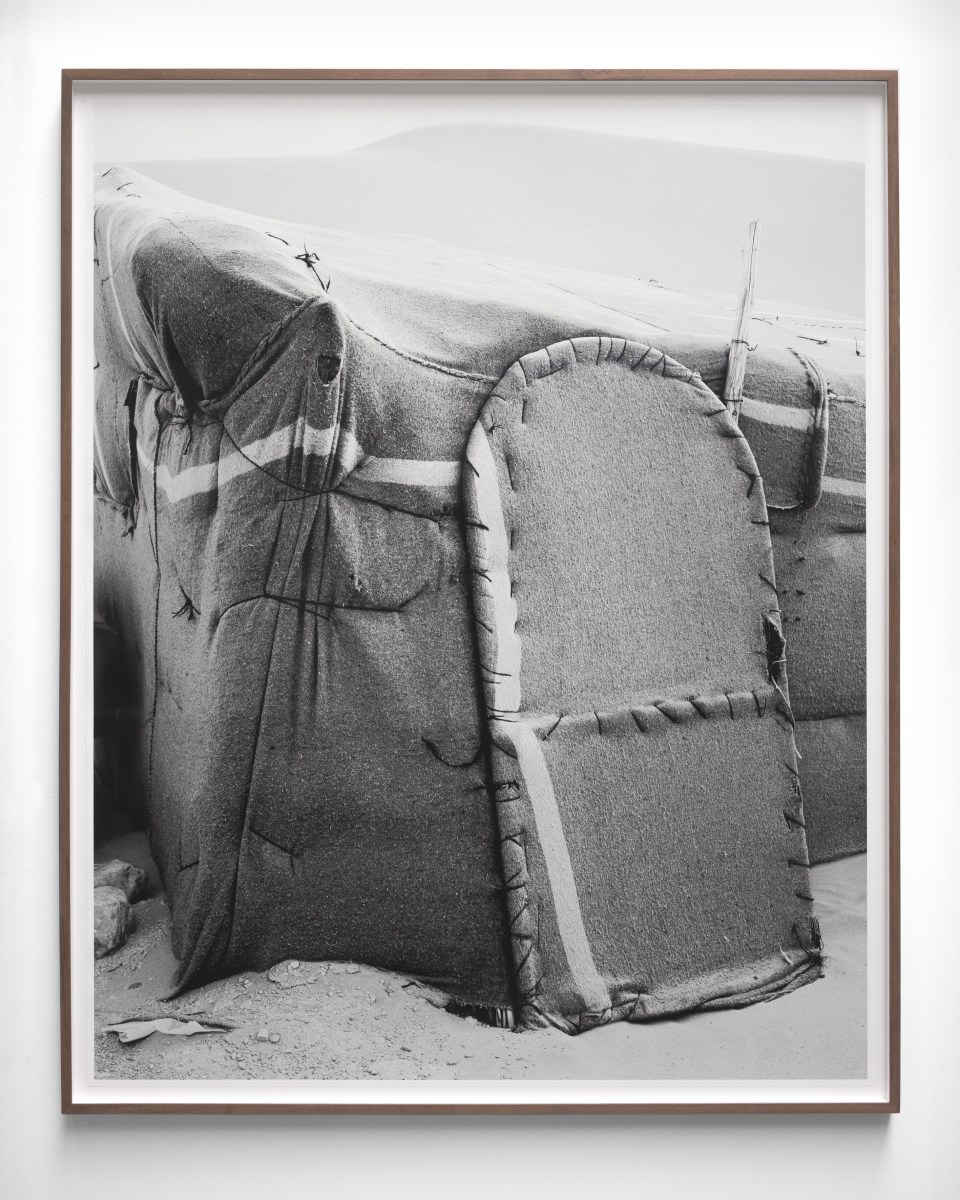

Sybren Vanoverberghe, There were plants and birds and rocks and things 01, 2023, KETELEER GALLERY

What inspired you to create the Desert Spirals series?

I am fascinated by the ‘nothingness’ of the desert. For this series, I photographed the desert landscape with different types of shelters, each with a certain temporality. You notice there is a sort of 'shelter' in some places of varying levels of permanence for a person who has travelled through this landscape. Other shelters have been there for a very long time and are permanently inhabited. It was this transient yet circular aspect of the landscape that led me to create this series.

How do you start such an unusual and challenging undertaking?

I add image after image to an archive already containing images from previous series. I leave those images for a longer period of time so as not to get too attached to the moment they were photographed. Everything that comes afterwards is quite intuitive: the selection of images, the making of test prints, choice of formats and finishing process in my studio.

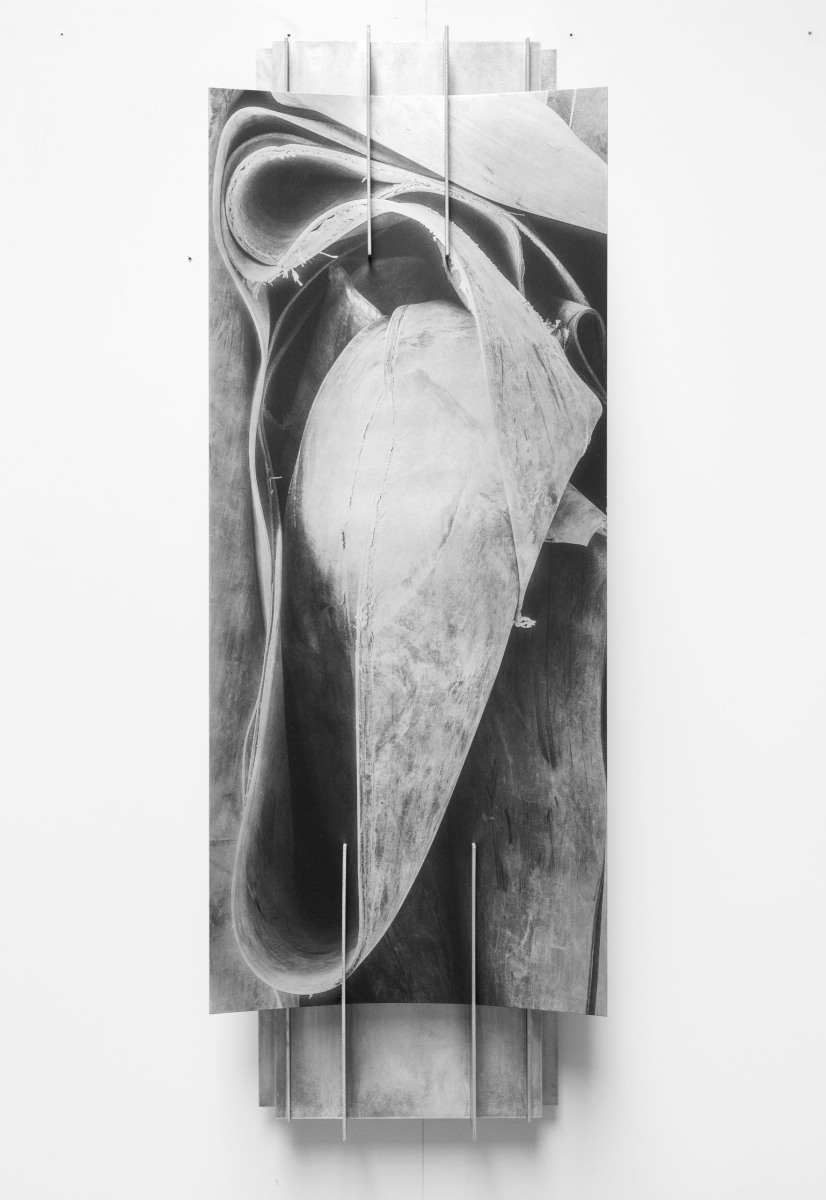

Sybren Vanoverberghe, Display Screen Wall Sculpture 01, 2023, KETELEER GALLERY

How has the overarching theme of 'nothingness' in the desert influenced your work, both past and present?

Photography is a highly suitable medium for working with the 'nothingness' in a landscape. As a photographer, you work with what is available to you wherever you to happen be. In this case, the 'nothingness' works for me as a silent place that can be visualised, a place that does not cry out for attention, but has a certain peace. That's what I wanted achieve with this series. In the desert, things simply exist as they are. Places change but some things stay the same for centuries. The desolate expanse of the desert allows me to isolate and observe specific things.

How did you go about finding and documenting traces of the past in a desert landscape?

By driving around intuitively and seeing where it takes me. In this way, different places begin to relate in an associative way based on their construction method and location within the landscape. Many of the shelters photographed will probably be abandoned someday and taken over and used by someone else. So, in that sense, it is not always about a 'distant' past, but it may very well be about yesterday.

I decided to show things as they presented themselves to me. This also happened in my previous series through the use of light and other elements. I just wanted to show the prevailing silence of the places I visited in my images.

What should we make of the (traces of) human presence depicted in your pictures and their significance?

Human presence can be seen in my work, but almost never directly. Traces and artifacts, a footprint in the sand or a ruin within a landscape are images of this indirect presence. I think that the significance of such traces consists primarily in 'being' and they do not necessarily amount to anything greater. It is the archive and entirety of images from different projects that come together after a while and provide a certain associative value rather than having a direct or distinct significance.

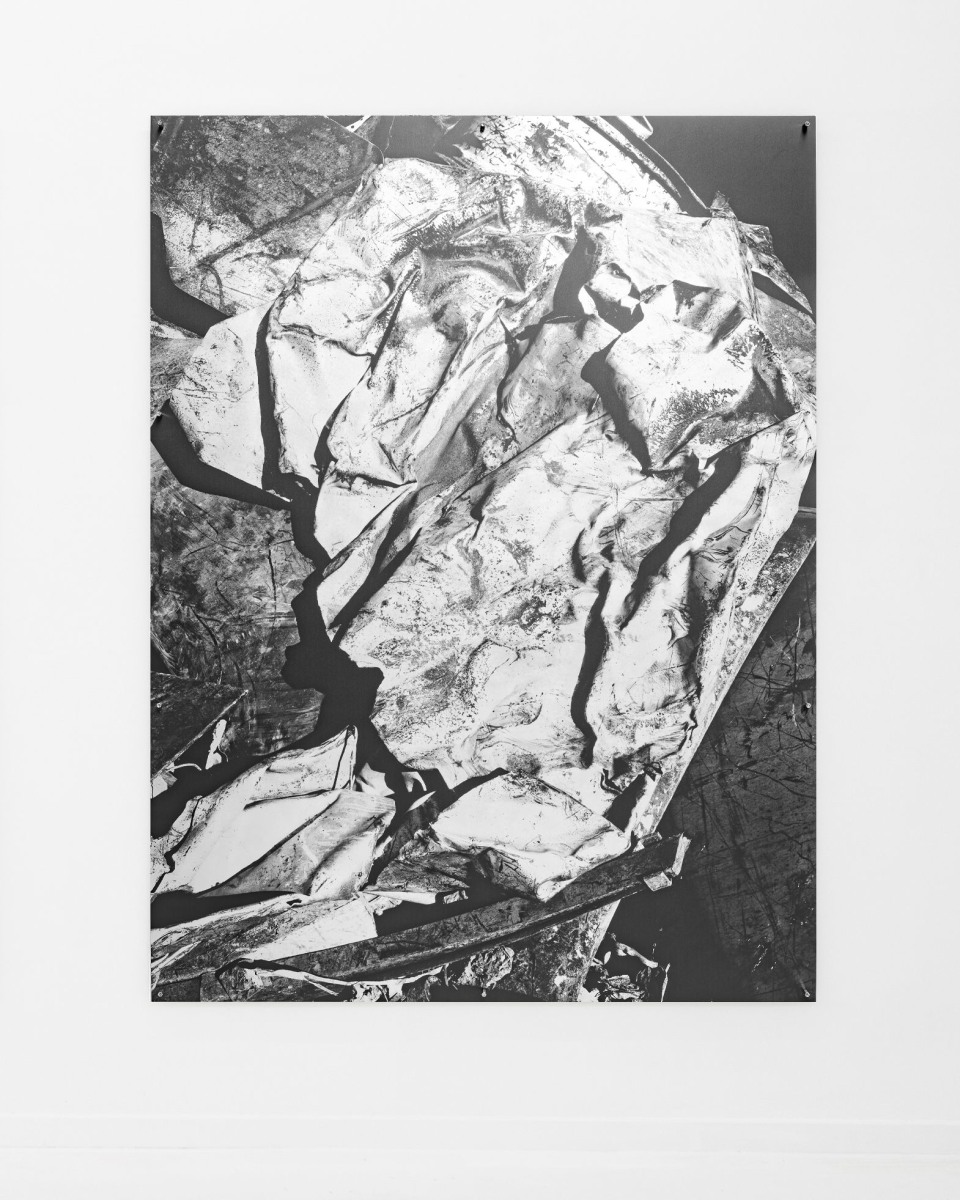

Sybren Vanoverberghe, Display Screen 32, 2023, KETELEER GALLERY

How would you describe the relationship between past and present, time and place, in your work?

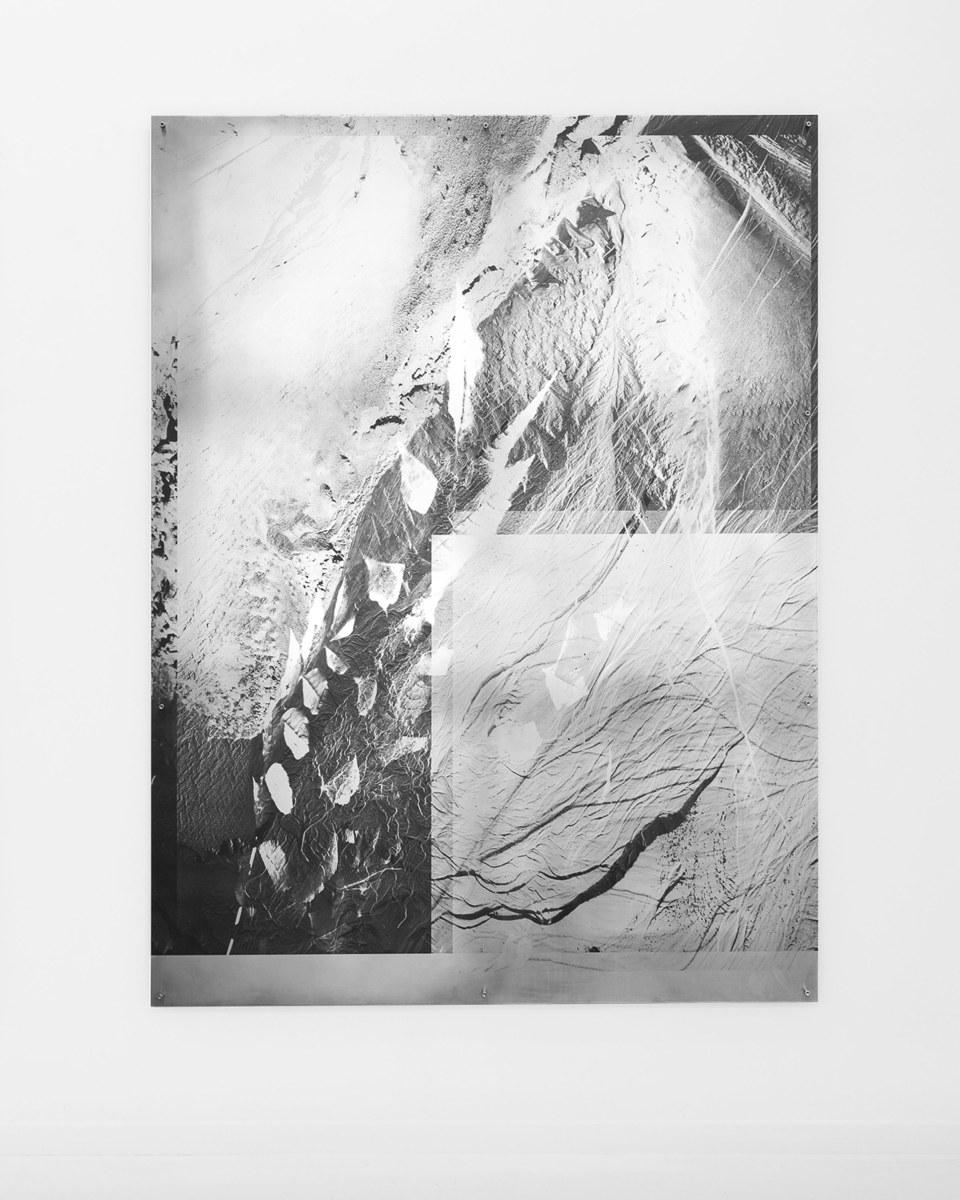

I think that accumulating a series of images, which then find their way into publications or exhibitions, is necessary to create a relationship between past, present and future. By recording dilapidated constructions, artifacts in archaeological museums or crumbled boulders, it is possible to focus on the transience of certain objects as well as the function of these things in the past.

Things get interesting when certain interfaces can be discovered over the years, such as an entrance to a silo in the Port of Ghent showing an association with the entrance to a house made of mud in the Moroccan desert. Photographing 'sites' and 'non-sites' is a form of activation and making both yourself and the viewer aware of your observations, with a focus on how time and place continuously interact.

For me, observation and photography in themselves do not immediately translate into a decoding of the subject matter. It may be like an attempt to archive what you are looking at and to weigh up how one thing relates to the other. The landscape and what is found in it always manifests itself in a different form, but is related to the previous landscape that was photographed and observed.

Sybren Vanoverberghe, Display Screen 01, 2022, KETELEER GALLERY

For this exhibition, you are working together with architect Theo De Meyer, who is responsible for the scenography of the exhibition. Did this collaboration affect Desert Spirals?

The collaboration with Theo De Meyer started after he set up my studio. Theo has a specific view on what architecture can be and how materiality and form play an important role in that. He often works with existing building materials, which he designs into configurations in which form and content go hand in hand. Because of the influence that architecture has on my work, I decided to ask Theo if he would like to join me on a trip to the Moroccan desert for two weeks and then work together on the scenography. Being on the road together resulted in a fascinating collaboration in which two different visual languages collide. What makes the scenography so interesting are the details in the constructions and material choices Theo has made. These are very close to the nuances that can also be seen in the work on the walls. The scenography will consist of various gates and doors that will be set up in Keteleer Gallery. Frederick Keteleer gave us carte blanche to partially convert the gallery into an installation-oriented scenography in which the gallery is divided into various compartments and spaces where clusters of images will be displayed. The fascinating thing about it is that it makes you aware of your movements before entering another part of the gallery.

How do you look back on past exhibitions now that Desert Spirals is a fact?

In a way, every image builds on a previous image and every exhibition. The same can be said of publications. It is only after some time has passed that I am starting to understand the importance of creating an image archive and seeing how the images relate to each other. It is not always clear why you want to capture something, but that is also why photography continues to fascinate me.

Sybren Vanoverberghe,Display Screen 29, 2023, KETELEER GALLERY