09 may 2023, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Josse Pyl

For Josse Pyl, our daily environment is one huge language web. His work explores how all elements of this web – from letters, lines and images to touch and emotions – influence our understanding of the world around us. In his work, which often consist of several panels, all these different forms of linguistics come together in visual sentences that unfold in spatial environments. For his new work, currently on display as part of the group exhibition A bee's wing dropping onto your cheek by Annet Gelink, he found inspiration in early Disney films.

Where is your studio located and what does it look like?

My studio is currently located at Broedplaats Bouw in Amsterdam in an old school building. The layout of my studio always varies depending on what I'm working on. Often, there are lots of materials lying around and I have to clean up regularly. But once my work is finished, I usually put everything away, so I don't repeat myself too much. I also often put aside what I’m currently working on, only to take everything out again a few weeks later and look at it with fresh eyes. I want there to be enough time in between, so that I no longer fully remember the work and can see new things in it. At some point, everything comes together and the studio becomes chaotic again.

Josse Pyl in his studio, photo by Lonneke van der Palen

What does a typical day in your studio look like?

I don't have a set structure for my work process. Some days, there are things that are ready to be assembled into a new work, exhibition or installation and there are other things that need to be taken care of. Also, I always try to work on ideas with an end result that is still unknown. I don't plan what work I will be doing the next day, so every day brings new challenges and I never know what will happen. Once ideas come together to form a new installation or presentation, I get an inkling of what needs to be done, but at that point, I also try to free up time to work on new things.

What are your minimum requirements for a studio space?

Since I sometimes work with larger and heavier installations and machines, and with lots of materials, I need at least a studio on the ground floor, preferably with a high ceiling and natural daylight.

Two of your new works are currently on display in the group exhibition A bee's wing dropping onto your cheek. They consist of several panels of painted glass. I notice that you often change medium. In recent years, you have worked on paper, cardboard, polyethylene (cutting boards), plaster blocks and now glass plates. Why is that?

In my work, I use different materials to understand and dissect the language landscape around us. I examine language itself as a kind of malleable material that shapes our environment and thinking. How language is made up of more than just words. It is about how we express ourselves in all kinds of forms and everywhere in our environment. It is like a symphony of symbols, sounds and movements, which we express with our body and mouth through visual and mechanical messages. Our environment is actually one huge language web in which different areas of knowledge come together, thereby creating an entity of different realities and perspectives. I explore all those forms of communication hidden around us and how they shape our thinking and interactions with each other and the world.

Josse Pyl in his studio, photo by Lonneke van der Palen

Can you explain how you try to understand that language web, that system?

I try to understand this complicated system by pulling it apart. For example, how signs and thoughts flow through bodies and realities, how language and speech form and dissolve into a circular structure. I make drawings, sculptures and videos that come together in spatial environments where language, knowledge and body parts come to life and are lost again. I investigate how these elements come together without hierarchy and can be combined into architectural installations. I use everyday materials such as concrete, plaster, paper, stone, cement and epoxies that mimic the body, and now also glass, to achieve this.

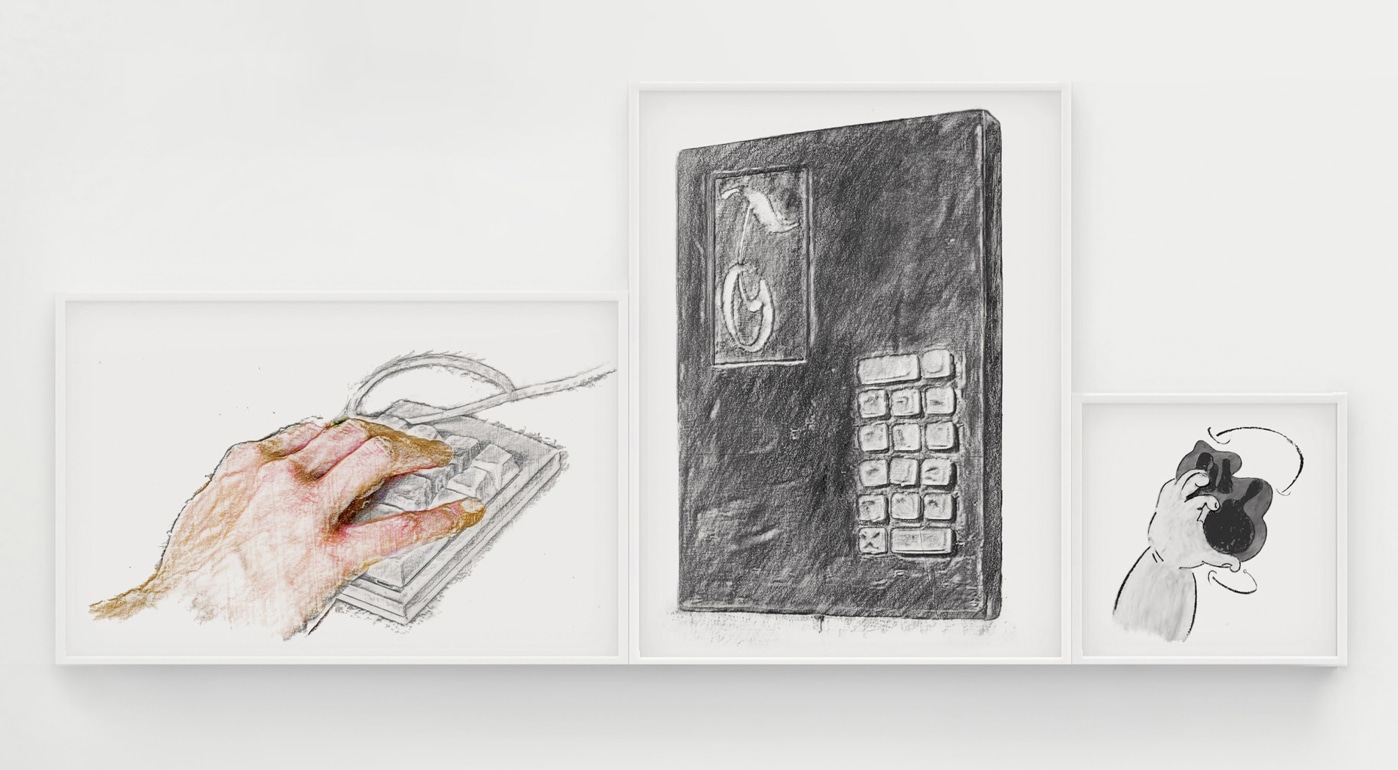

Josse Pyl, A Hat with Two Feet and an 'I’, 2023, Annet Gelink Gallery

By using materials with a history and physical presence in our environment, I try to create a connection between the exhibition space and world around it. By using these materials and paying attention not only to the traditional forms of communication, but also forms that are often overlooked, such as the feeling of being touched, the emotions we experience and the knowledge we form through our body and physical interaction with the world we live in.

These forms of expression, while not always considered conventional ways of thinking, play a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the world and the knowledge found within it. My works therefore emphasise the materiality and physicality of the environment, often making them feel like part of the environment in which they are displayed. This allows me to create linguistic environments in which different expressions of language unfold as sentences in space. Consequently, language becomes a physical part of the environment, cast in industrial or everyday materials.

How did you come up with the idea for the glass plates?

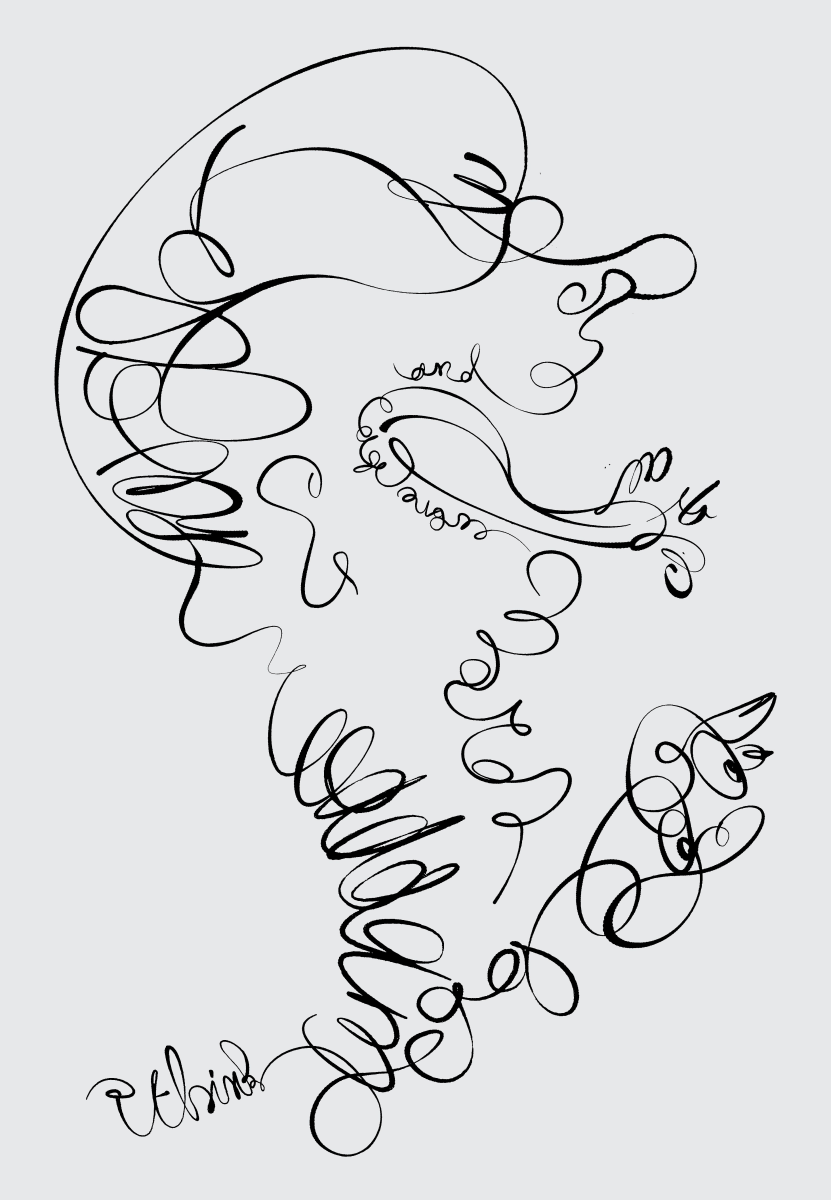

The initial ideas for these works emerged on paper last summer during a stay at the Frans Masereel Centrum, where I experimented with different graphic production and printing techniques, including the offset press. I became fascinated with using a single line to recreate and depict the world around us, using a print of a single line to represent different perspectives and realities. This can create a reflection, caricature or representation of our daily experiences, dreams and amazement. A line can form the outline of a letter, word, problem or grammar, but also the legs, torso, eyes, mouth or costume of a figure representing a person, plant or animal.

Josse Pyl, and i THINK a thought I think i've THOUGHT, 2023, Annet Gelink Gallery

I took visual elements of language and took them apart to create an alphabet of lines. By doing this, I wanted to explore the relationship between language, the alphabet and the networks that connect printing to the world. Using a laser cutter, I cut out these lines and printed them into new configurations with an offset press.

After returning to Amsterdam, did you then start developing that idea further?

After my residency, I started working again on making spatial environments and became fascinated by window structures. During my research, I came across sketches of a technique used in early Disney animations called multiplane animation. Images were painted on glass and several plates were placed on top of each other. These images were then photographed, allowing 2D lines to be transformed into perspective, rotation and dimensions using glass and resulting in animation.

When I unwrapped the prints I made during my residency, these two ideas came together. I was inspired by the compositions of the multiplane technique and decided to create window structures that would allow me to create a three-dimensional and moving syntax. By using glass as a medium, a sense of movement could be created in these works.

Can you explain how these works are constructed?

The glass plates are constructed as a body and building with bolts and joints. A kind of alphabet of lines is created on the glass, which together form a sense of figures. Each sentence becomes a living organism that creates a syntax of movement. Layers are built, lines dance and stretch, creating a chain of transformation and possibilities. The works therefore explore the potential of the line and become a kind of breathing entity that can reflect, connect and parody the world in which we live.

The works that can now be seen form a kind of 'visual sense'. That's a fairly recent invention of yours, is it not? With each drawing standing on its own. Do you remember when this idea was born?

I got the idea of 'visual sentences' when I made my artist book i THINK and I think i've THOUGHT a thought. In it, I went in search of how printing techniques and languages try to structure and understand our society. I wanted to find out how I could use those techniques to create new meanings in the paper world of a book. I used the frottage technique to explore motifs and themes from my work and translate them into the pages of the book. This technique lets you capture images of environments by pressing them against paper. I placed paper over elements of my work and rubbed the surfaces with a pencil, making the shadows of my work appear on the paper.

Each page of the book therefore reflected the structure of elements from different works. Language arises from objects it wants to represent and forms a shadow of reality. Letters and prints are between images and surfaces, between objects and text, and between language and the world. Sight and language overlap and lead to a world full of knowledge and imagination. The pages together formed a mix of images and characters that described these images. As a result, the book became an object that could be read, spoken or deciphered.

Josse Pyl, I Think and I Think I’ve Thought a Thought, 2019, Annet Gelink Gallery

Can you explain the latter?

By superimposing the fragmented parts of the book, new associations and ways of reading emerged on each page. This gave rise to the idea of having the original drawings unfold as text in the physical space. This way, the works developed into visual sentences. Drawing after drawing, the vocabulary of semantic artifacts was unravelled and the interwoven system that shapes our thinking and daily life became visible.

I then also made moulds and casts of the drawings and objects as a means to create three-dimensional sentences in space for the CA NTS EE MY TO NGU E exhibition at the gallery last year. I transformed The Bakery into an archaeological environment by copying and destroying the walls. I then worked the fragments and added symbols and signs using the moulds, creating a grammar of reliefs in space that made a decaying language tangible. Using this technique, different expressions of language unfolded as visual sentences in space and gave new meaning to the environment.

Josse Pyl, CA NTS EE MY TO NGU E, 2022, Annet Gelink Gallery

Mouths, teeth, molars, loose letters, strings of calligraphy and calculators frequently feature in your work. What do these elements symbolise?

These elements often symbolise the mechanisms that connect one human being to another. They are symbols that are not meant to depict anything specific, but rather represent something in a certain, agreed-on way. They articulate thoughts and emotions, as well as the systems we develop to communicate them and the names we give them. So, I use language as a fragment and an action, similar to a statement, which is not only a statement, but also an action. These symbols often reflect the core meanings and associations they evoke, such as the ordering of signs, the sound of typing, the grinding of teeth, the making of typos, the formation of words, as well as the rumination and swallowing of thoughts and emotions. In my sculptures, drawings and videos, these symbols together form a conversation about language and invite the viewer to read their writing. They act as language fragments that can be used to generate new, free associations and to create poetic scenes and stories. For example, many of these symbols are present in a stop-motion video I made titled Inner Word in Outer World, in which I explored the function of the mouth as a portal between the inner and outer world and used teeth as a personal keyboard for interpersonal communication. By following the drawings, the viewer takes a journey through a mouth in which teeth show an illusion of decayed language. Language thus emerges from the bones of our voices and communication is reduced to the physical intimacy of the mouth. Frame by frame, the language kept behind our teeth escapes, while the drawings turn the mouth into a ruin of our former words and worldviews.