14 april 2023, Wouter van den Eijkel

In Nature Nobody Would Care For You Either – Luis Xertu’s candid new work

“In nature nobody would care for you either.” Quite a statement coming from your father. Luis Xertu was told these words and left for the Netherlands soon after. Almost 20 years later, he processes the break with his family in his second solo exhibition. Whereas he previously hid the meaning of his canvases in coded language, Xertu is clear for the first time about the meaning of his work.

Luis Xertu (1985) grew up in a wealthy family in Mexico. He moved to the Netherlands in 2004. He was educated as an independent artist and graphic designer at the Rietveld Academy. He then worked in the theatre world for over 10 years and is still responsible for the graphic design of De Parade, the traveling preview of the upcoming theatre season. He has only displayed his autonomous work for a number of years now, which is characterised by half-naked men, black backgrounds, dried plants and more recently, gold leaf.

Whereas in his first show, Xertu reverted to the tradition of code language that homosexual artists often use, the story In Nature Nobody Would Care For You Either is more explicit and much more personal. This is the story of Xertu's parents' divorce and the consequences it had for him, from moving to the Netherlands to ultimately severing all ties with his father and the feeling of not really belonging anywhere.

Xertu: “My parents' divorce became a kind of War of the Roses and they started using us [the kids, ed.] as a means to attack each other. My mother in particular was an easy target if her children were not well cared for. She was a housewife who was suddenly divorced, had no power and was constantly being punished through us.

The divorce put me in a schizophrenic situation where I was rich one day and poor the next. My father had a penthouse with a swimming pool, while my mother did not have enough money to make ends meet. In addition, you were manipulated all the time: if you don't do what I want, you will be kicked out of the house and you will have to live with the other person. It's not about what you have or don't have, but about the fact that someone sees you as property. People with that mindset very often talk about nature as if it were a perfect mirror of our lives.”

That nature metaphor is also the reason why Xertu uses many animals to tell his personal story. Animals fleeing a natural disaster, finding their way outside the herd. Xertu skilfully combines the theatrics of impending mayhem with titles that describe a painstaking process of isolation, such as Recoil, Seclusion, Withdrawal and Premonition.

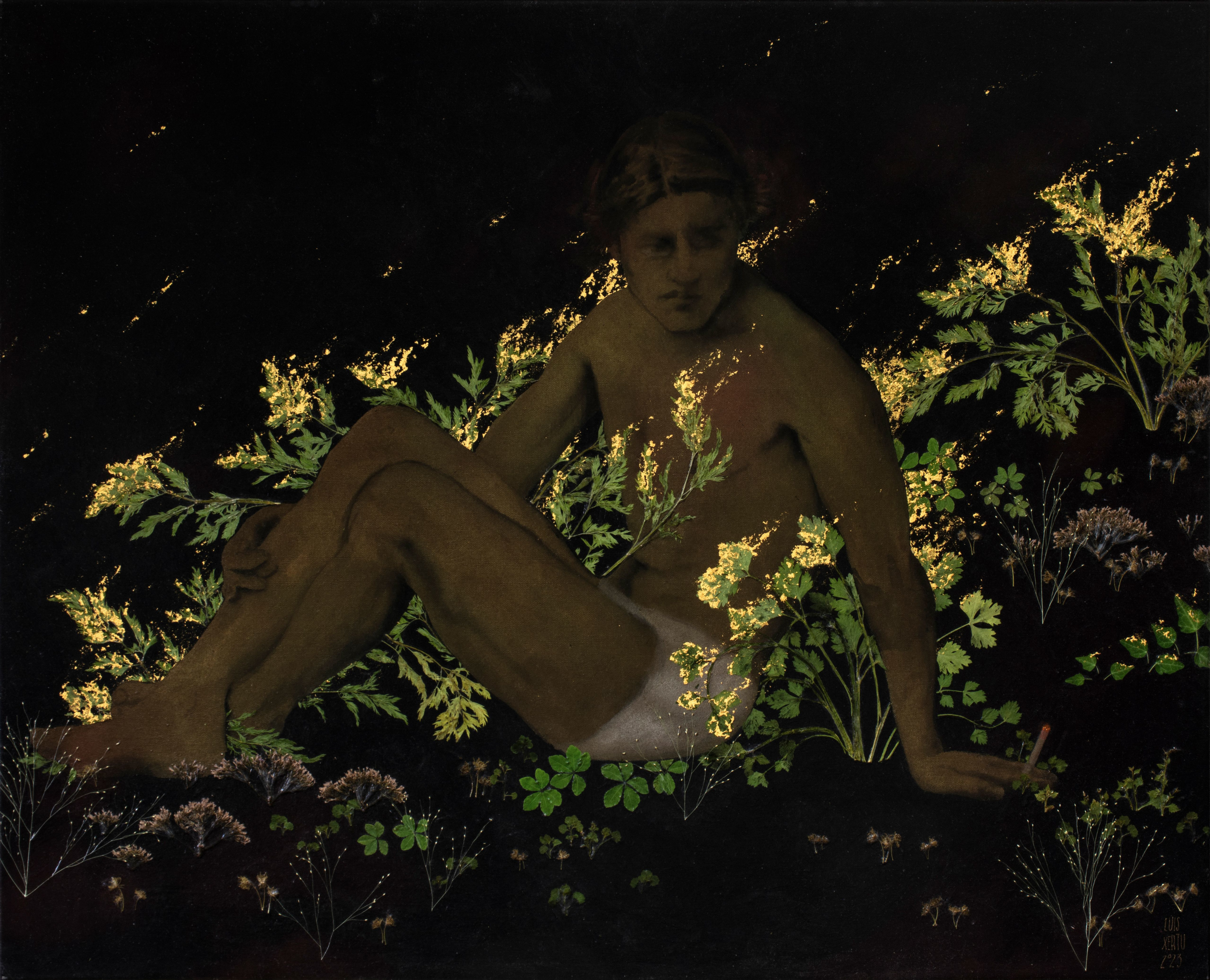

In the front room, there are mainly works with ‘animals of the rich’, such as macaws, dogs and horses. On Rumination, a work that does have a human in it, disaster is slowly approaching. “Here [in the front room of the gallery], it's all very nice and very relaxed, but at a certain point, the higher social classes also come into contact with the tragedy. It's very subtle, but he's smoking a cigarette among the flames. That is what is happening now with the upper classes. They worry as much as everyone else, but they are also very comfortable.”

Rumination is also the first painting for which Xertu used gold leaf to depict flames. “I noticed that it had a very intense shiny effect and I thought: it’s actually funny when you make things burn with gold because of the metaphor. Wouldn't it be nice to show wildfires? But also because of the class relations; the notion of the collector who wants to have a forest fire is twofold. On the one hand, you have the greed that gold is typically associated with, while on the other hand, it is also very beautiful. Often, we have a complicated relationship with things that can kill us. A tragedy like a forest fire can also be quite beautiful. That makes our relationship with climate change very complicated and layered, as suddenly it is no longer so clear-cut.”

In the works in the back room, we mainly see wild animals that are either confronted with impending natural disaster or locked up. For example, we see six gibbons in The Bloodline is Kept Alive. One of the white spider monkeys has isolated itself. “For me, this work is about whether or not there is conflict. If you look at how the painting is constructed, you can see that it’s a kind of zoo. It's not nature. Those animals may think that they have a very organic relationship with each other, but in the end, they are just prisoners.”

Luis Xertu, Seclusion, 2022, TORCH Gallery

In Seclusion, a red fox in the midst of a gold-leaf bog fire turns his gaze towards somewhere outside the frame, where the forest fire, judging by the fox's attitude, is even fiercer. On A life in the woods, two deer fight against a bright red and golden yellow background. It is also the only work with is a clear perspective in the scene. That in itself is not spectacular, but if you consider that Xertu always incorporates plants in his works, this also means that they must also align with the rest of the representation.

Luis Xertu, A Life in the Woods, 2023, TORCH Gallery

The use of plants (especially ferns, weeds and carrot tops) and almost standard black background give Xertu's work a unique and immediately recognisable quality. That raises the question of why he debuted so late. Did his autonomous work go unnoticed or did he not want to go public with it?

Xertu: “All my creative energy went into graphic design. It wasn't until four or five years ago that I finally dared to be myself. That also has to do with the decision to break off contact with my father. I used to think I was suffering from chronic depression, but suddenly I was no longer depressed. All this time, I was with someone who was poisoning the water. You don't notice it because you've always been in that water. That's why I only allowed myself to have my own opinion later on, to develop my own style. I developed my visual style secretly and I told my story in a cryptic way: if you look closely, you can see it. You act like nothing's wrong, but underneath it, I was trying to send out SOS signals all the time. It was all I knew.”