02 october 2025, Yves Joris

The sheriff who never arrived: Francis Henri Vanhee at NQ Gallery

In this village, nothing is what it seems, every face a mask, every detail a clue that explains everything and nothing. The village is both familiar and frightening, a place that draws you in precisely because you would never want to live there.

Francis Vanhee, The village (No escape), 2025, NQ Gallery

A village full of doppelgängers

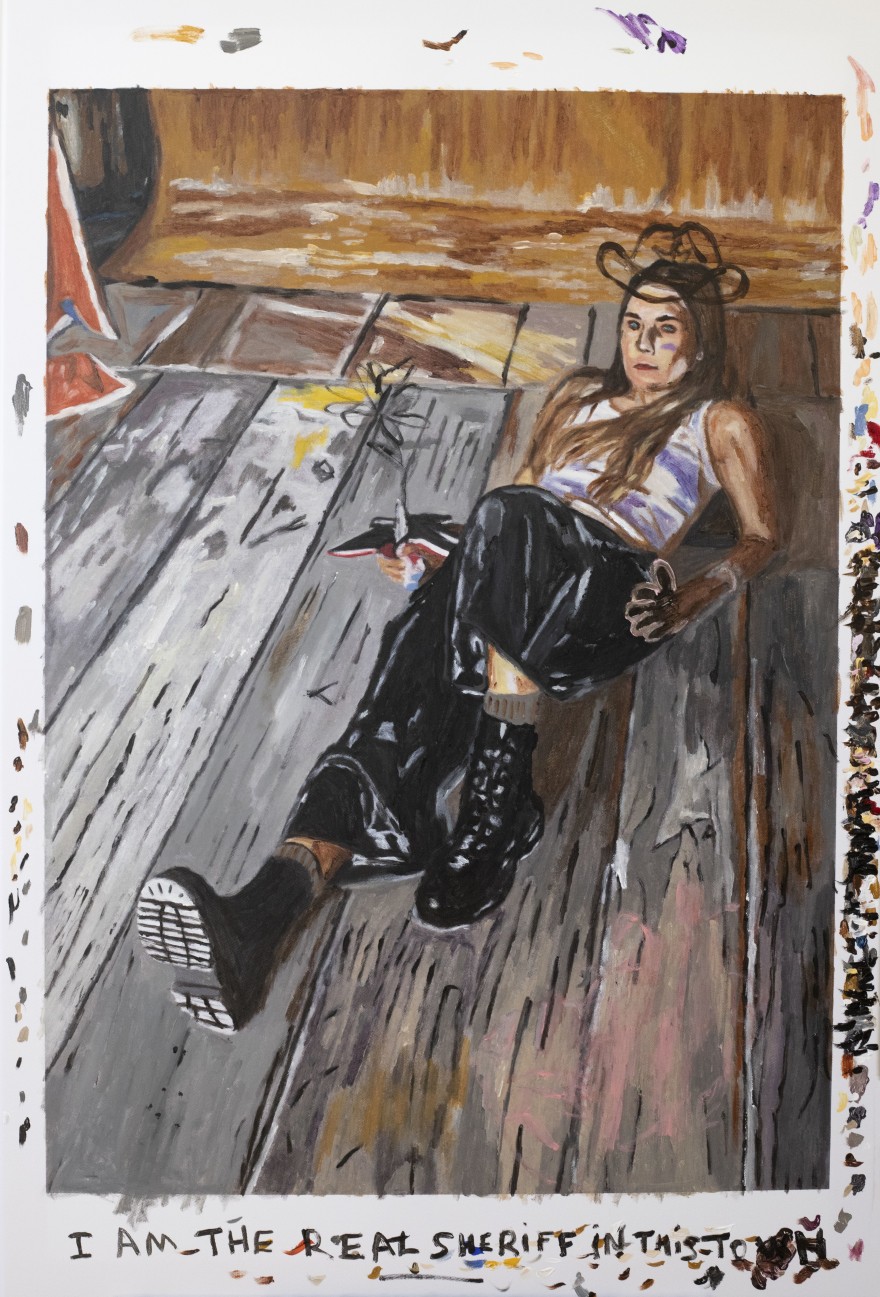

Vanhee’s fictional village is a walled enclave. The wall is not only architecture, but a symbol of isolation, of how communities deceive themselves into a carefully directed illusion of safety. Inside those walls, figures populate the stage who look suspiciously like real people, but in reality, have been reduced to shadows. Christophe Vekeman, for instance, appears as a sheriff, but stripped of his soul. The mask Vanhee gives him turns him into a cowboy without a story, a caricature of authority. At the same time, actress Lauren Müller, who plays a police officer in the soap Thuis, becomes the ‘real’ sheriff of this village. Roles and reality intertwine, as if Vanhee is creating a mirror in which no one can recognise themselves.

This game of doppelgängers has an unheimlich quality that seems borrowed from Lynch. Like in Twin Peaks, you get the feeling that the characters have accidentally landed in the script. They move as if an invisible hand dictates their actions, trapped in a narrative from which there is no escape. The night-animal spotter, based on actor Spencer Bogaert, is a striking example. His existence revolves around one ritual: lighting a cigarette before heading into the night. The image Vanhee creates resembles a young James Dean. The gesture is banal, but in Vanhee’s universe becomes destiny. And so a village emerges in which even the smallest action carries an echo of doom and meaning.

Francis Vanhee, The Artist, 2025, NQ Gallery

The artist as criminal

Perhaps most revealing is Vanhee’s self-portrait, in which he depicts himself with a clumsy body and a childlike, almost awkward face. The work bears a text that both reinforces and provides ironic commentary on the image: Rinus doesn’t have a patent on putting captions under a piece of work. But anyway back to the story. He is the village artist, or the village fool, or the village criminal. Apparently, an artist and a criminal have the same kind of brain. PS I LOVE YOUR WORK RINUS.

With these words, Vanhee is assuming an ambiguous position. On the one hand, he acknowledges his kinship with Rinus Van de Velde, who consistently links image and text. On the other, he positions himself as an artist who writes his own narrative, fearless and with a touch of irony. Here, the artist is not an exalted creator, but a figure balancing between fool and criminal. The notion that artist and criminal share the same brain suggests that creativity and rule-breaking are two sides of the same coin.

The small printed words under the chair — SEARCHING WHILE — function as an anchor in the composition. They connect torso and floor, idea and act. KICKING on the right reads like a fragment of a statement, a movement unfinished and all the more exciting for it. The red X marks a spot on the floor, a site of confrontation or forbidden movement. Together, these typographic and pictorial elements create a theatrical place marker: something is happening here that we are not fully allowed to understand. The text at the bottom is both reproach and homage; Vanhee claims Rinus has no monopoly on captioning images, yet places himself in a tradition he affectionately questions.

What is also striking about this work is the visibility of the process. Along the edges of the canvas are colour samples, traces of the artist’s hand. During the opening of the exhibition, Vanhee told Nicky Aerts that he often starts from photos in his archive, which he then edits with oil pastel and enlarges onto canvas. This working method explains the layering: photographic base, drawn lines, oil pastel smudges and finally, paint. The mask-like head is a drawn layer resting on the painted body. The clash between the naive face and broadly painted torso is disruptive. It makes the person both recognisable and unrecognisable, which is precisely the point. The photo as starting point remains visible in the colder, photographic registers of colour and lighting. Yet the painter’s hand is always audible in the scratching letters and loose brushstrokes.

Francis Vanhee, The mayor, 2025, NQ Gallery

The village as mirror

The fictional mayor of Vanhee’s village is both laughable and sinister. He lives in an apartment block and looks down on his subjects from the top floor, martini in hand. The image is familiar: those with power basking in luxury, while the inhabitants of their domain toil in misery. The dictator realises he has ruined everything, but there is no way back. He continues to reign because power sustains itself, even when it has been completely hollowed out. Here lies the bitterness of Vanhee’s work: his village is a mirror of the world we live in, a world full of mini dictatorships that never call themselves that, but that rule with an iron hand all the same.

The architect of the village, a woman wearing the artist’s suit, is Vanhee’s alter ego. She is both the designer and prisoner of the village. Through this exploration of identities, it becomes clear that Vanhee’s work is not mere observation, but also self-reflection. He stands at the heart of his fictional universe, both maker and character, creator and victim.

Francis Vanhee, The Architect, 2025, NQ Gallery

The influence of cinema and literature

The resemblance to Lynch is evident, but literary echoes also slip through Vanhee’s universe. His village recalls the claustrophobic microcosm of Franz Kafka in which power is unfathomable and omnipresent. At the same time, a melancholic humour resonates that recalls Louis Paul Boon and Dimitri Verhulst, writers who dissected human misery in their own villages with both laughter and tears.

The cinematic quality of Vanhee’s work is unmistakable. Each painting is a scene, a frame that seems part of a larger story. Yet he refuses to complete that story. Like Lynch, he leaves room for the viewer to make connections, to wander through the village and project their own plot onto it.

Conclusion

Francis Henri Vanhee’s village is a hall of mirrors. Behind every mask hides another mask, behind every detail another story. It is a universe in which the boundary between humour and tragedy continuously shifts. You linger there not because you want to live there, but because you recognise yourself in it, distorted and magnified.

Vanhee invites us to wander through that walled world, not to find answers, but to foster questions. And as always in good art, it is not about solving the riddles, but about enduring their presence. His village is stranger than fiction, but perhaps all the more recognisable for that very reason.

Francis Vanhee, The real sheriff, 2025, NQ Gallery