30 september 2025, Yves Joris

Humanity resides in the crack: Thameur Mejri at Uitstalling Art Gallery

“I let my hand move faster than my mind.”

– Thameur Mejri

Sometimes it is not the completed gesture that touches us, but rather the misstep, the line that goes astray and therefore carries more truth than a perfect form ever could. Thameur Mejri knows this better than anyone. He does not draw, paint or scratch to smooth out the image, but to make the crack visible, the misstep tangible. Amanda M. Maples, art historian and curator of African Art at the New Orleans Museum of Art, who wrote the exhibition text for We Are Made From Mistakes in Uitstalling Art Gallery, once described Mejri’s oeuvre as an ‘architecture of errors’, a house full of cracks, sloping floors and windows that do not quite close. It is an image that fits this exhibition remarkably well. After all, in We Are Made From Mistakes, flaws become not failures, but foundations on which meaning rests.

The confession of hands and feet

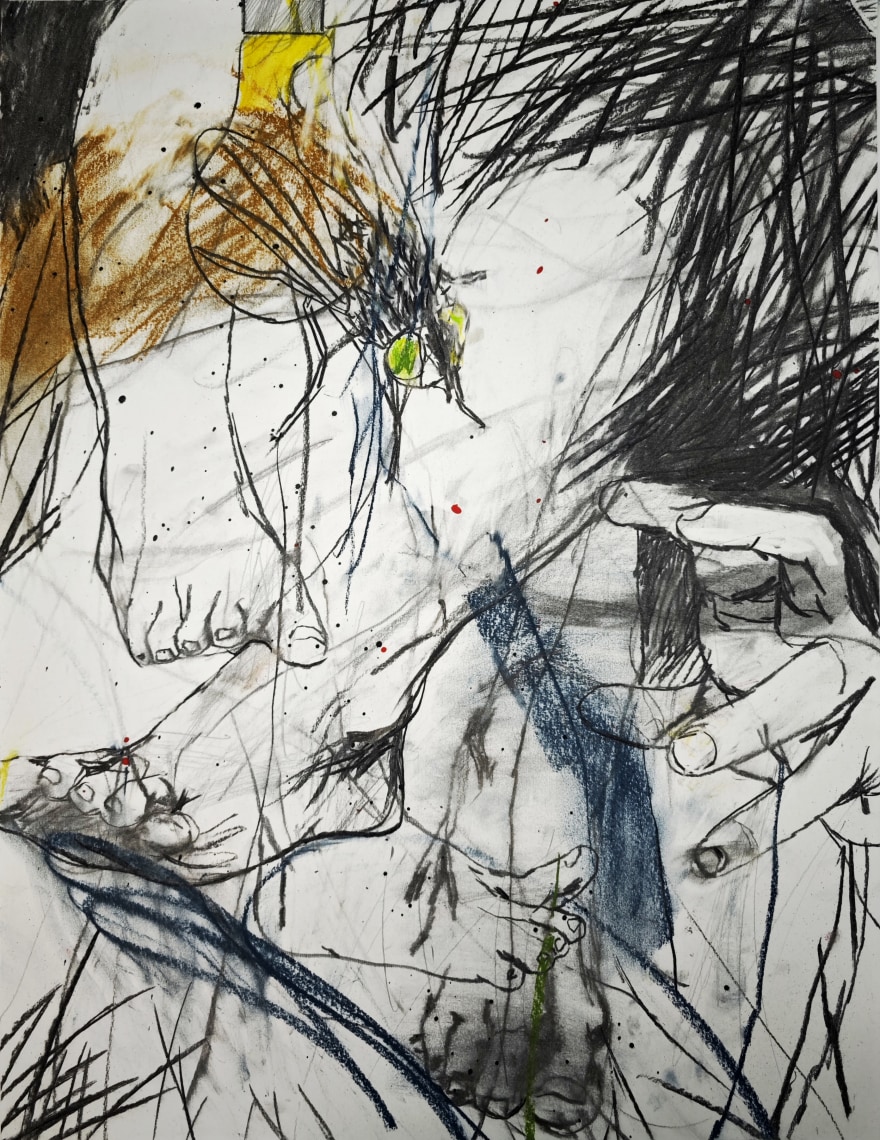

It is striking that, for the first time in his career, Mejri did not begin with an image or intuition, but with a title. We Are Made From Mistakes is a phrase that resonates like a bassline throughout the entire series. It gave him the freedom to let his hand move faster than his head, to give the body’s reflexes precedence over the mind’s calculations. The result is a gesture that no longer tries to erase the error, but admits and embraces it. Using charcoal, pastels and acrylics, he lets the lines run where they will. It is as if he is saying: let the hand do as it pleases; it knows more than the brain that constantly corrects.

The drawings in this series are smaller than what we are used to from Mejri, who is known for his monumental gestures. Here, he has chosen intimacy, the direct closeness of paper and charcoal. Interestingly, the same motifs recur again and again: hands and feet. Not proud bodies or faces, but body parts. The foot that carries us, the hand that lets us act – here detached from their context to become vulnerable symbols in themselves. The inner sole, soft and receptive, takes on a religious connotation. The artist makes reference to a ‘Christ complex’, the stigmata of hands and feet as places where suffering and redemption coincide. Yet Mejri’s imagery is not aimed at transcendence, but is about making tangible the vulnerability that binds us, our collective confessions.

Thameur Mejri, Architecture of error 1, 2025, Uitstalling Art Gallery

Lamp and fly: an allegory of progress

The fact that he omits so much in this work is equally as significant. The rest of the body often disappears, as if the very image of humanity has succumbed to pressure and is falling apart. Whereas earlier series featured an excess of motifs—knives, sneakers, toys, mythological figures—there is a narrowing here. Only two icons remain prominent: the lamp and the fly.

The lamp represents ideas, ingenuity and human progress, yet also refers to the dark underside of innovation, the destructive shadow of the Manhattan Project, the atomic bomb born from a brilliant idea. The fly, by contrast, is the silent spectator. Indifferent and ubiquitous, a banal witness to our failures, one that may even outlive our downfall. Together they form an allegory of the ambiguity of our existence: the lamp as hope and danger, the fly as the indifferent measure against which our dramatic presence seems to carry no weight.

The viewer experiences a continuous oscillation between figuration and abstraction. From afar, they seem like abstract compositions, but up close, recognisable fragments emerge: a knife, a shoe, a limb. It is as if the image continuously wants to hide and reveal itself, as if Mejri is forcing the viewer to take on an active, searching gaze. It makes his art uncomfortable and piercing. He keeps us searching, has us wander throughout the stratification of his visual language.

The lesson of the mistake

There is also a political undertone to all this. Mejri’s work originates from a context in which art can never be purely personal, but often coincides with the social and political reality. His work is a mirror for regimes that refuse to admit mistakes, that cling to a façade of perfection. Rarely do political leaders acknowledge their errors, yet recognition of missteps is the only path towards change. In that sense, his art becomes an ethical appeal: accept that you are mortal and fallible, not only as an individual, but also as a community.

Thameur Mejri, Flawed Origins & The Fracture, 2025, Uitstalling Art Gallery

The intimate and black-and-white of his drawings take shape in colour in his paintings. Two tones dominate: red and blue. Archetypal opposites symbolising fire and water, passion and stillness, life and death. In Flawed Origins and The Fracture, these forces clash. The red glows like a wound, the blue covers, but can also suffocate. Here, there is no reconciliation, no harmony, but a constant oscillation that reminds us of the tensions that run through our existence.

And yet this work does not breathe pessimism alone. It is also an invitation to gentleness. In a culture that commands us to live flawlessly, to stack success upon success, Mejri says that we truly exist only in and through our mistakes. Failure is not a shadow to erase, but a trace that marks us and makes us human. In that trace lies not only our vulnerability, but also our strength.

Those who visit the exhibition get a good sense of how his work simultaneously attracts and repels. It forces you to look at what you would rather avoid: the failed gesture, the unfinished, the crack. And precisely in that unfinished aspect lies the poetry. The incomplete here becomes not a shortcoming, but a space of meaning. As if every line that suddenly stops, every white space on paper, is an invitation to participate, to become part of the process itself.

Perhaps that is what makes this exhibition so significant: it teaches us to look anew at mistakes, not as something to be corrected, but as a source of meaning. This applies on a personal level, but just as much to a society struggling with its own past and political systems blind to their missteps. In Mejri’s art, the mistake becomes a mirror in which we see ourselves—sometimes painfully, sometimes liberatingly, but always truthfully.

We Are Made From Mistakes is therefore more than just a title. It is an attitude towards life, an aesthetic, an ethic. In an age in which filters, cosmetics and artificial perfection dominate our daily images, Mejri reminds us that the crack is the only place where truth shines through. His art tells us to live with our mistakes, learn from them, carry them as scars that signify both beauty and humanity. And perhaps that is the most profound lesson of these works, that it is not the smooth surfaces that shape us, but the fractures that break us open.

Thameur Mejri, We Are Made From Mistakes, Uitstalling Gallery

Biographical note

Thameur Mejri was born in Tunis in 1982 and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Nabeul. Through his uncle, who was a painter, he became acquainted with studio work at a young age. Painting was not a choice, but an inevitable path. Alongside his artistic practice, he is also a lecturer at the École Supérieure des Sciences et Technologies du Design in Tunis. His oeuvre is influenced by artists such as Francis Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci and Vladimir Veličković, but equally by film, literature and the political context of North Africa. Mejri’s work explores the tension between the individual and the collective, between body and power, between hope and destruction. His paintings and drawings have been exhibited internationally, including in France, Senegal, Egypt and the United States. In each of these contexts, his theme resounds: the imperfection of humanity as a source of beauty and truth.