12 september 2025, Martine Bontjes

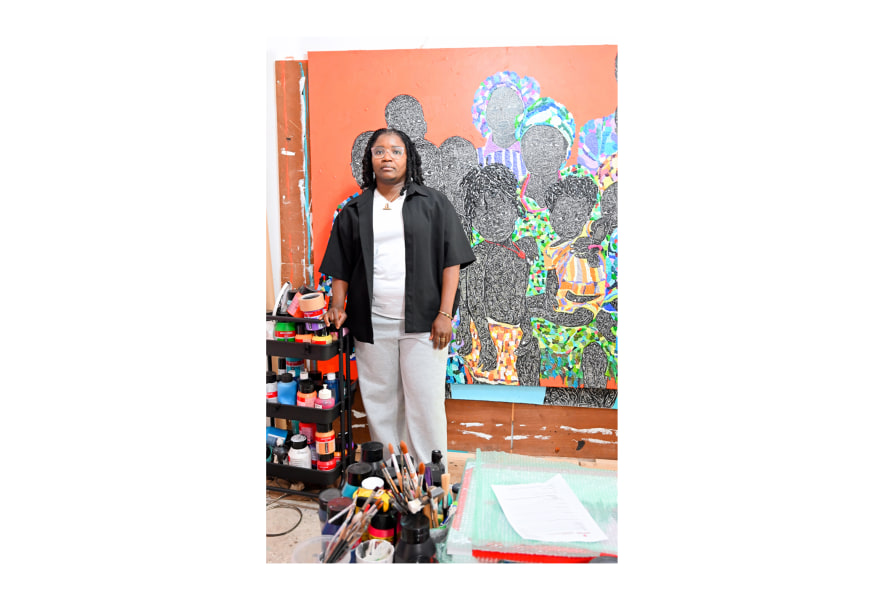

The studio of... Tyna Adebowale

Tyna Adebowale creates her own matriarchal society in her Amsterdam studio. She is surrounded by books from Audre Lorde and Oyeronke Oyewumi, while music by Arya Starr and Sabrina Carpenter fills the space. Through her paintings, Adebowale shows that the leadership of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and the Egba women of the 1940s was not an exception, but once the norm. They were builders of economies, mediators in conflicts, and defenders of their communities. Adebowale advocates for the revival of matriarchal structures: “If women are better educated and supported to develop stronger self-awareness of their power, there could be a revival of leadership in building healthier, more collective communities.”

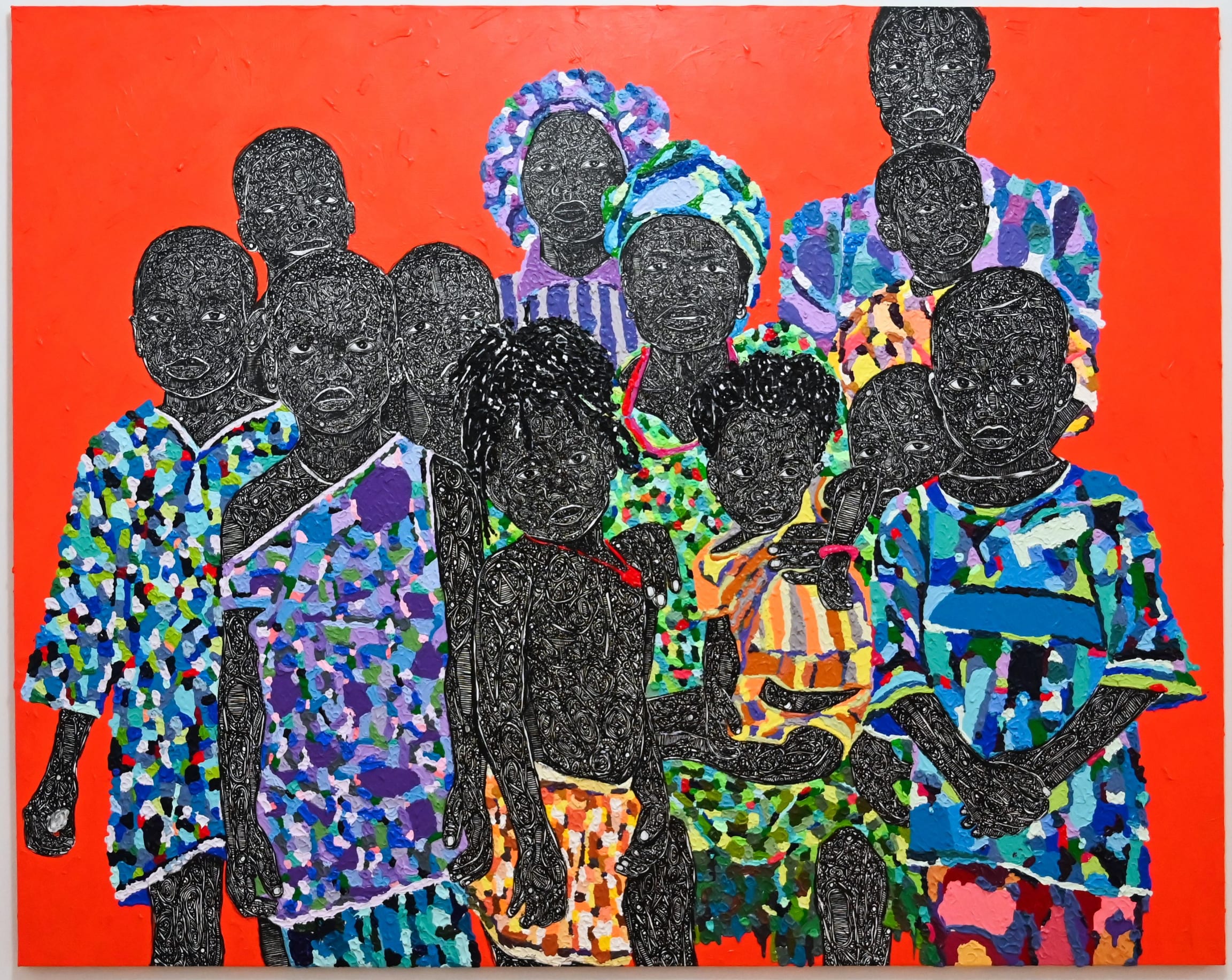

The gazes of her figures and her choice of monumental formats give her paintings an impressive, almost physical presence: "You cannot ignore them, just like the stories they carry." Adebowale’s work can be seen until October 18 in the exhibition "They Call You Mother; They Call Me Mama" at Ellen de Bruijne Projects in Amsterdam."

Your studio is in Amsterdam, but your research takes place in Nigeria. How do you combine this?

I am currently responding to your questions from my Amsterdam studio, although I also maintain project spaces in Nigeria that support my practice and research as an artist. I have named the Amsterdam studio ‘Obé’. In Yoruba culture, this word literally translates to ‘pepper’ or ‘soup.’ Among the Yorubas of West Africa, pepper holds significance in both culinary and spiritual practices. Its fiery and potent nature is believed to align with the energy and personality of the Orishas, symbolizing power, vigour, and the ability to bring about both positive and negative outcomes, depending on how individuals engage with Obé.

What is the first thing you do when you enter your studio? Are there certain rituals that help you get into your work mode?

Nowadays, I like to start my studio days slowly, usually with a cup of black coffee, tea, or warm lemon water. I spend a few quiet moments observing my works in progress before diving into any major productivity for the day. This helps me ease into a creative flow.

Tyna Adebowale, Motherwomb series, 2025, Ellen de Bruijne Projects

What are the essential tools you always need around you while working? Or are there any specific voices, music, or sounds you listen to?

My essential tools for making paintings are of course, a wide range of colours. Or specific palette tones as I want or need to use for specific project/work. I also enjoy having human voices around me while I work. This is usually through podcasts or online conversations. I find that listening to people talk, whether in structured discussions or more organic chats, creates a lively and inspiring atmosphere for me in the studio. More recently, I delved into listening to and analyzing the music of women such as Paris Paloma, Arya Starr, Sabrina Carpenter, Fave, Alexa Evellyn, Sofia Isela and other very strong women voices. I use their music to relax after my work for the day.

Conversations are an important part of your practice. How does that process work, from conversation to physical paintings?

A central part of my practice involves engaging in conversations as a method of inquiry and expression. Through talking, asking questions, and listening deeply, I explore the lived experiences of women, individuals, and communities. These exchanges become both a research process and an artistic medium. It is an unfolding archive of voices, memories, and shared knowledge. This form of socially engaged practice allows me to investigate personal and collective narratives of women in the Uneme and surrounding communities, often shaping the visual, and performative elements of my work. In the Uneme community where I grew up, it is common for a child to be raised not only by their biological mother but also by several maternal figures. This communal way of parenting is natural there, though it is less common in many other places.

In #motherwombproject, I interwove memories of my great aunt, Mama Niidezedo, who was both a spiritual gateway and a sacred facilitator in her community. Mama was deeply respected for her spiritual wisdom and lifelong work as a healer, mediator, midwife, and strong matriarch until her passing in 2015. Mama had no biological children but she was truly a mother to all.

Tyna Adebowale, Motherwomb series, 2025, Ellen de Bruijne Projects

Do you see your art as a form of advocacy and celebration for these grandmothers, or more as a documentation of their lived experiences?

My work is layered. It is both advocacy and documentation. It celebrates the lives of women and grandmothers while also recording their lived realities. Growing up, I witnessed the toxic culture where men rarely, if ever, say ‘thank you’ to women, no matter how supportive or selfless the women have been. That culture of never appreciating the workload of being a woman still exists even today with younger men. In many of our cultures, women’s voices have been pushed into the shadows, even though for generations they have been the solid pillars upholding and carrying entire communities.

The #motherwombproject seeks to continue honouring women. To continue bringing their stories into light. Many women have been conditioned into humility and silence, never realizing the weight of the labour they carry, or how hard they have worked and how this has shaped us all over the years, growing up.

How do you visually represent something intangible as ‘care’?

The visual representation of ‘care’ is never absent in my practice. In my large paintings, it may appear subtle or even flat at first glance, but it is solidly present and visible throughout the works. First of all, there is a very deliberate motive of why these paintings are large. You cannot ignore them, just like the stories they carry. For me, care is a verb and entails action and not mere words. My practice extends beyond the canvas and other forms of tools I use.

Tyna Adebowale, Motherwomb series, 2025, Ellen de Bruijne Projects

I saw you made a mobile library filled with books. What books or writers inspired you for your latest works?

I would say the Mobile Library Project was the first womb of connections I created in Amsterdam. It grew very organically, especially during the lockdowns. At first, I had carefully mapped out how I would use it across neighbourhoods, but over time, circumstances allowed it to flow into some of the most beautiful projects that included sounds, became a dj set, creating several memories. These projects were also shaped by the people I encountered through the library itself. So I let it be, and allowed it to evolve naturally. Months later, the library birthed the project Ovwa/Thuis/Ireshi/Home. It showed at the first Refresh Amsterdam.

The collection holds many inspiring books that I sometimes reference in the studio. Works by writers such as Buchi Emecheta, Audre Lorde, Queen Afua, and Oyeronke Oyewumi. For me, the most important ‘books’ in my practice remain the human library: the lived experiences of women whose stories continue to shape and inspire my projects.

Do you believe matriarchal structures could return in some form, or if not, what everyday practices of care and resistance can we cultivate to build on their legacy?

In a country like Nigeria, many of us remember not-too-distant times when society was already culturally toxic, but not nearly as extreme as what we experience today. Over the last 15 years of political transition, my pressing question has been: how the hell did we allow men to take over all the power? They are often unhealthy, self-centered, and far too unaccountable to be entrusted with such autonomy. But an even more painful question for me is how and why did women allow this to happen?

The answer lies partly in oppressive structures, such as the church, which have historically suppressed women’s voices. In recent years, we have also witnessed how women with strong voices are silenced as soon as they begin to gain an audience. By contrast, when matriarchal structures were more present, Nigeria was a healthier and more balanced place to grow up. History reminds us of these women and to name a few like Queen Mother Idia of Benin, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, and the Egba women who led the Abeokuta Women’s Revolt of the 1940s. These women were not only leaders but builders of economies, mediators of conflict, and defenders of their people. They proved that women’s leadership was never the exception, it was once the norm.

I remain hopeful that change is possible. If women are better educated and supported to develop stronger self-awareness of their power, there could be a revival of leadership in building healthier, more collective communities. Communities less centered on men, and more centered on care, responsibility, and shared humanity.

Are you working on future projects at the moment?

The one I am able to share right now is my upcoming participation in the collective exhibition Out: LGBTQ+ Artist-Activists of Africa at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC, early Winter 2026 – Summer 2026.

Tyna Adebowale, Motherwomb series, 2024, Ellen de Bruijne Projects