09 june 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Aaron-Victor Peeters

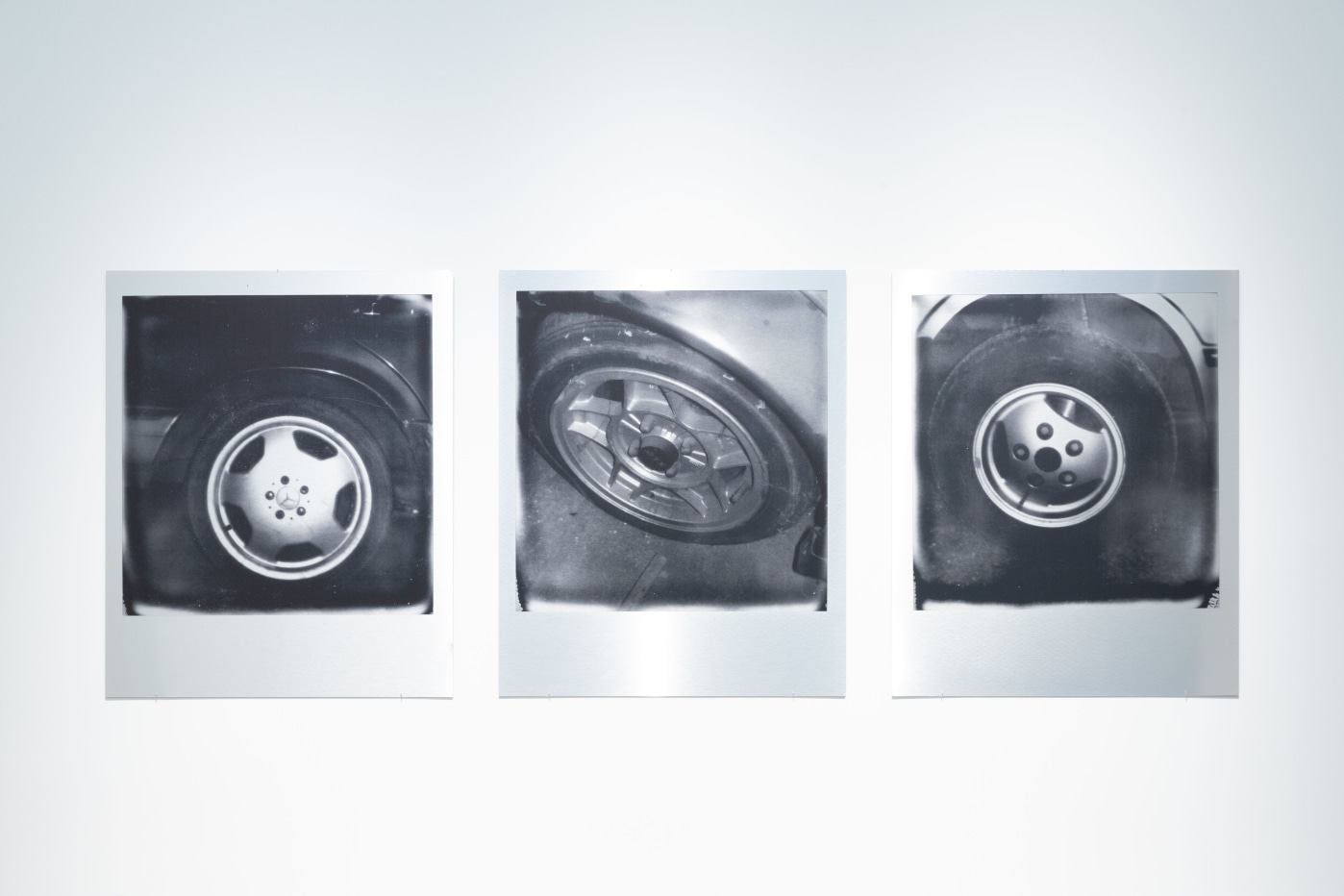

At first glance, Aaron-Victor Peeters’ studio looks more like a car garage than an artist’s workshop—which is not surprising, as it’s the former depot of a bus company. In this large space, Peeters stores cars he purchases from everywhere and anywhere. To Peeters, they don’t need to be drivable. "To me, a car is more than just a means of transportation; it’s also a vehicle—a carrier onto which I can project dreams and desires."

Later this month, on 18, 19, and 21 June, Peeters will be opening his studio to visitors. Unlike many of his fellow artists, Peeters enjoys receiving guests and sees added value in it for them. "I always find it interesting to invite people into my studio because the context of the work changes completely—when you see my paintings or drawings hanging among the cars or when you get to browse through my collection of Pirelli posters. Despite its size, the studio remains an intimate place."

Interested in visiting Aaron-Victor Peeters’ studio? To register, send an e-mail to [email protected].

I read that you buy old cars and store them in your studio. So, I imagine you have a massive warehouse at your disposal. Can you describe what it looks like?

Massive might be a bit of an exaggeration, but compared to an average studio, I do have quite a lot of space. My studio is the former depot of a bus company. When you first enter, it really looks more like a car garage than an artist’s studio. Only after sliding open an additional gate do you enter the area where I draw and paint.

Aaron-Victor Peeters

Besides having a lot of space, what does a good studio absolutely need in your opinion?

Tools! I often find myself limited in making an artwork because I don’t have the right tools for the job. This is something I’m focusing on all the time—buying what I need so that my studio is a true creation space.

Suppose I were to intern with you. What would an average day in the studio look like?

Everything starts with coffee. And there’s almost always something that needs to be tidied up before we can get started—but this cleaning often results in new work or ideas. When I pick up two things that normally wouldn’t be connected, I start thinking about what new story they might tell together. I always try to get interns to actively build and create—laying out structures, welding—but also visiting locations or preparing invoices. Drawing and painting is a more solitary endeavour, which I prefer to do alone.

Aaron-Victor Peeters, 7 nights in Stalenstraat, 2024, Uitstalling Art Gallery

On the subject of the cars: they also appear in your work. Why are you fascinated by cars and what do they represent in your art?

For some reason, I’m haunted by cars. It started with my first Mercedes—its engine exploded a month after I bought it. When I was preparing the paperwork to sell it, I saw it had rolled off the assembly line on 20 October 1994—the day I was born. I thought, “This Mercedes is trying to kill me” and that became the first title in a series of car-inspired works. Beyond that, a car is more than a vehicle to me; it’s also a vessel for projecting dreams and desires.

Aaron-Victor Peeters, Untitled, 2024, Uitstalling Art Gallery

Is that also why you like 1970s sci-fi?

I love 1970s sci-fi because it often tried to depict the future we’re now living in. And we take so many things for granted. The way things were visualised in the 1970s reflects this contrast more clearly. In Soylent Green, for instance, the agent still looks like a kind of sheriff.

In your solo exhibition, Rum Runner, a covered wagon took centre stage. It was placed in the middle of the gallery, ready to depart—but of course, it didn’t move. Inside, you could watch spaghetti westerns. The questions it raised were: what is real and does it even matter when it comes to traveling in spirit only? Is that a major theme for you?

Exactly. I started with the idea of myself as a child—a child who could travel to other worlds in his imagination. In this work, I question what’s real and what’s fictional. Our image of America, for example, is shaped by these spaghetti westerns—films shot in Italy or Spain based on stories by a German writer (Karl May) who had never actually been to America.

Aaron-Victor Peeters, On The Road, 2024, Uitstalling Art Gallery

Your gallerist tells me you’ll soon be opening your studio to collectors and visitors. When will that be and what can we expect?

On 18, 19 and 29 June, I’ll be opening my studio to the public. And that’s a good excuse for me to clean it up! I always find it interesting to invite people into my studio because the context of the work changes completely—seeing my paintings or drawings next to the cars or browsing through my collection of Pirelli posters. Despite its size, the studio remains an intimate space. And I think there’s always value in meeting an artist in his or her own habitat.

You’re in your early 30s now. What do you hope to be doing in the next five or so years?

Last year, I created a public space installation for the first time and I really enjoyed it. In a museum or exhibition, people have expectations—they know what they’re coming for. But if you’ve lived on the same street all your life and suddenly there’s a work of art there, that’s always unexpected. That interaction with a public that isn’t always open to art interests me. Beyond thinking about sustainability and vandalism, you’re also dealing with a public that didn’t choose to see your work. I hope to have the opportunity to take on more of those kinds of challenges.

What are you working on right now?

A Vespa PK50 from 1975—just kidding! I’m 3D printing an engine block. It’s a test or a model for eventually printing an entire car, which will become a light and sound installation. My seven-year-old son is doing the voice work for the sound effects. But everything is still under construction, meaning a lot of the initial concept can still change. That’s another fun thing about visiting my studio—you get to see design drawings of sculptures or installations that may end up looking completely different. It’s a great way to show how my thoughts are always evolving.

Aaron-Victor Peeters