24 march 2025, Emily Van Driessen

From Dead to Living Memory: what Kinshasa knows, what David Shongo questions

The exhibition 'From Dead to Living Memory' by David Shongo (1994, Democratic Republic of Congo) at Tommy Simoens Gallery in Antwerp explores the dynamic processes of memory, history, and their evolving narratives. "Memory is never only a space of accumulation of information, but it is, overall, an infinite activity of entanglement of events in space-time,” says David.

For David, memory is not a passive record but an active system, constantly shifting and evolving. "Cities function like computers; they are all subjected to an architectural system of information and an applicability of constant storage and treatment of this same information," he explains. "Some memories are fixed, like a hard drive (ROM), while others are rewritten in real time, like working memory (RAM). Congo’s colonial memory is a complex architecture, just like the memory of a computer. It is constituted by two types of memory: dead memory, a colonial library that we already know, like through archives, and living memory, which is abstract, a genealogy of the dead memory, and applies to the continuous present. To analyze colonial memory is to treat this binary system."

Kinshasa is a place where history is not just remembered but continuously reshaped. His work addresses this fluid nature of memory, revealing how the past is never static, it is always being rewritten in the present.

David Shongo, Café Kuba II, 2025, Tommy Simoens

Café Kuba: The City as a Witness

"Café Kuba" is the film at the heart of the exhibition. A mobile coffee vendor walks through Bandal, a district in Kinshasa, weaving through its streets and conversations. "Café Kuba" does not follow him as a protagonist in the traditional sense because the vendor doesn’t act or intervene. He listens.

David was drawn to these vendors for their quiet omnipresence. “They hear everything: political frustrations, love stories, gossip. They are like human recording devices, absorbing the city’s subconscious,” he says. The vendor’s silence makes him a mirror, reflecting the voices of Kinshasa without distortion.

"Café Kuba" was shot immediately after the M23 Rebel group attacked Goma and advanced toward Kinshasa, threatening the capital. The film captures the atmosphere of a city grappling with the awareness of an ongoing war alongside the everyday lives of its citizens. “There was this tension of an unknown future,” Shongo recalls. “The dead memory of the so-called First Congo War (1996–1997) is reactivated in the space. This reactivation is crucial, as it always comes back in Congo’s history.”

By framing Kinshasa through the lens of a dispositif that traverses space and time, "Café Kuba" turns the idea of documentary filmmaking inside out. Instead of delivering a single narrative, it presents the city as an archive, one that records itself piece by piece, conversation by conversation. “What was important in this video was to displace the power of the narrative and place Café Kuba’s path as a composition of a new archive, self-recorded and processing its own information.”

David Shongo, Blackout Poetry, Idea’s Genealogy II, 2023, Tommy Simoens

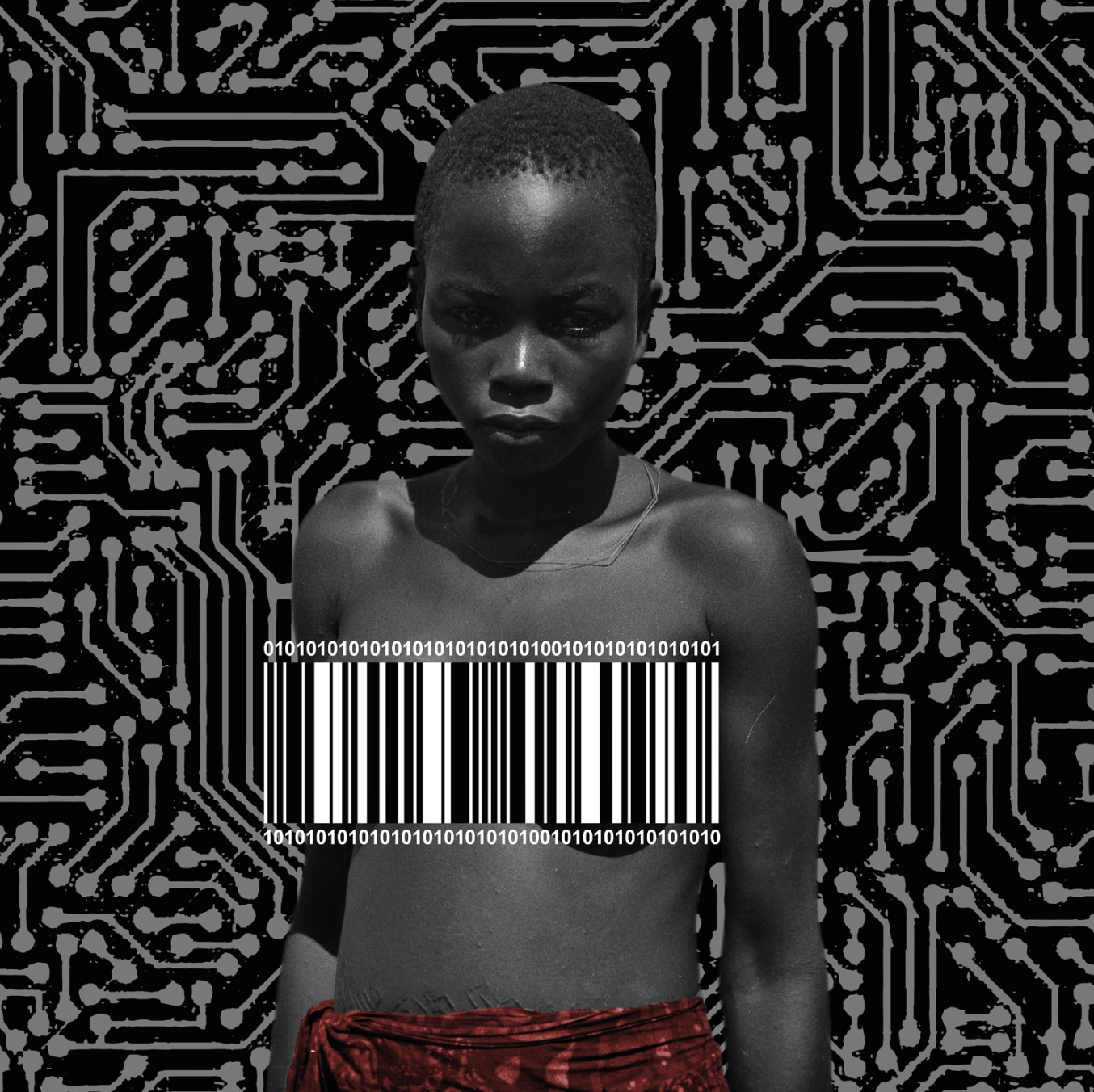

Blackout Poetry: the exploited land, the exploited body

If "Café Kuba" listens, "Blackout Poetry" interrupts. In this series, David reworks ethnographic photographs from the 1930s, images that were originally meant to control. "These photographs were never taken to be art," he says. "They were instruments of documentation, tools of a system that controlled bodies and narratives." Through strategic erasure, David alters their meaning, sometimes removing faces, sometimes certain body parts, and sometimes nearly everything but the background. The result is an unsettling absence.

Congo’s history is one of extraction. "Congo is not a country; it is an economic project," he states. "It always has been, from the rubber trade under Leopold II, to the uranium that fueled Hiroshima, to the coltan in our phones today.” The world has never engaged with Congo as a sovereign entity; it has only engaged with what can be taken from it. The land has been continuously mined, its resources fueling global industries while leaving behind a legacy of devastation.

But extraction did not stop at minerals; there was also the commodification of bodies. The Black body, especially the female body, was treated as an economic object. In one work, a woman’s torso is partially erased. The missing section is no accident, it forces the viewer to confront what was always there but never acknowledged: that the colonial gaze did not see individuals, it saw assets. "Bodies, especially those of women, have always been commodified in the space of Congo. They were used as merchandise to lure men, selling the idea that they could do whatever they wanted with those bodies. They were also used as weapons and as tools to dismantle social structures through specific violence applied to them. This is evident from the mutilations during colonization to the ongoing violence against women in the east.”

David also rejects the Western idea of "reclaiming" these images. "You cannot ask the victim to reappropriate the proof of a crime," he says. Instead, his work demands that the burden of interpretation shifts. “The violence embedded in colonial photographs does not constitute a history of the past but an active memory in the construction of the conscience of the country where the crimes were committed, as well as the country that committed them.”

David Shongo, Living Memory - Dead Memory, 2025, Tommy Simoens

Memories in motion

“I use music, film, video, sound, photography, all these elements are necessary,” he explains. “Because memory cannot be elaborated and created by one sense or through a single element. It’s a complex and interconnected system, like an informatic network of information.”

His work resists any attempt to pin history down into one definitive narrative. “Black history cannot be told with a single dimension,” he says. “It is a narrative enigma shaped by wounds, erasures, and resistance. Every Black memory is interconnected with global economic history.”

His exhibition demands engagement. It forces visitors to listen, observe, and rewrite their memory, just like the vendor in "Café Kuba" does in the bustling city of Kinshasa.