01 october 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

Ricardo van Eyk - LEVEL

Order and chaos are opposites, but can also coexist. Ricardo van Eyk proves this once again in LEVEL, his third solo exhibition at tegenboschvanvreden. In LEVEL, he has treated canvases coated with household, garden and kitchen paint, stucco mesh and screens using a knife, plugs and angle grinder. It may sound destructive, but has resulted in balanced compositions. We talked to Ricardo van Eyk about his new work, his working method and the unexpected effect his new studio had on the works in LEVEL.

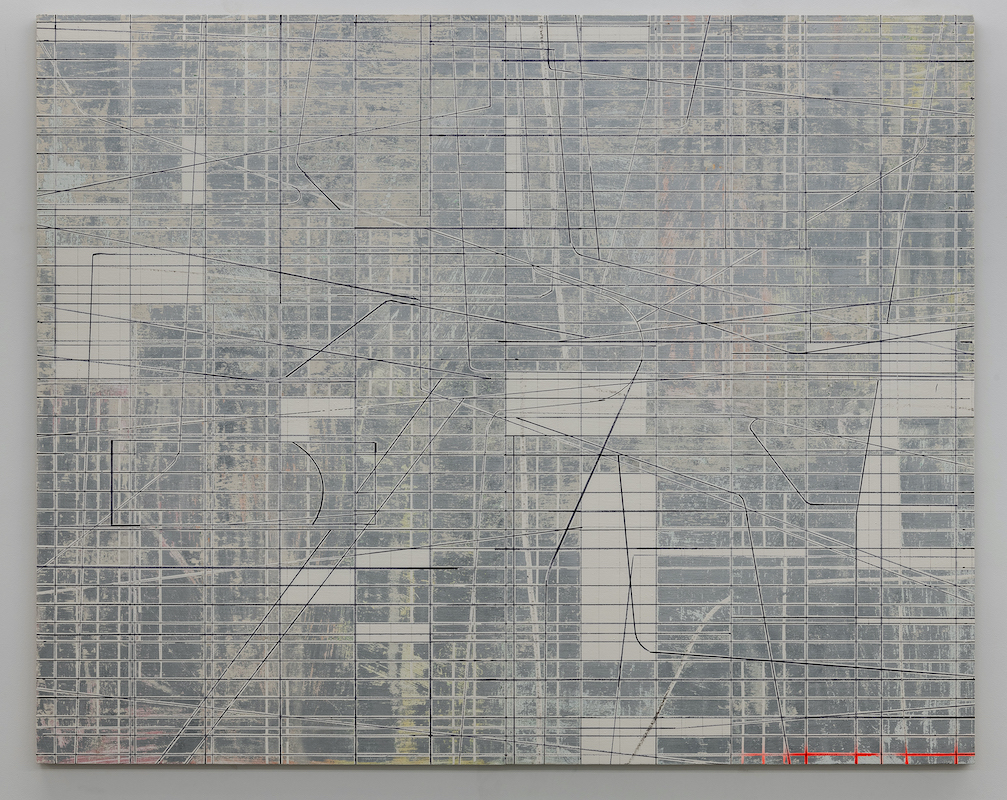

Ricardo van Eyk (1993) always gives his exhibitions five-letter names. The fact that LEVEL is also a palindrome is a nice plus, but no more than that. Van Eyk is mainly looking for a word whose meaning is somewhat ambivalent. The word ‘level’ means even or horizontal, but also refers to a floor or story of a building. “When you see the grid in a work like Century, it resembles a map or a city viewed from above. To me, that connection is also inherent in the word ‘level’. You immediately associate it with infrastructure or architecture,” says Van Eyk in the gallery.

Glitsa

That top-down perspective is a recurring theme in LEVEL. The recent works OPERA (SPURS) and OPERA (PLANE) I and II seem to refer to infrastructure, more specifically motorways and a roundabout interchange. If you interpret them that way, you see a convergence of lanes, exits and ramps. Whether that's the case is hard to say with Van Eyk, who is inspired by materials in public spaces, but generally avoids a direct translation from public space to the canvas.

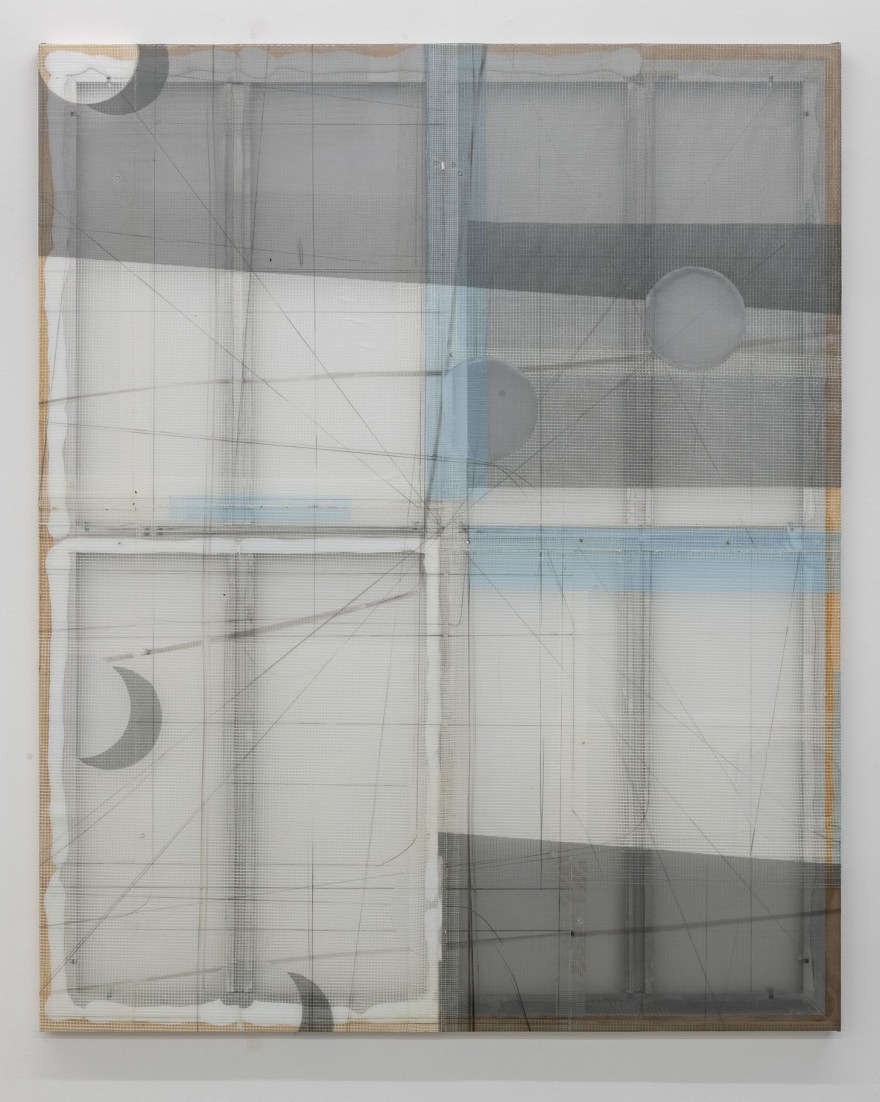

The three works from the OPERA series are composed, among other things, of layers of Glitsa and window screens. Glitsa is originally a parquet or furniture varnish with the unique property of being somewhat elastic, allowing it to accommodate the movement of wood. A few years ago, Van Eyk used it as varnish, but when he removed it, it resembled rice paper. This inspired him to explore whether Glitsa could be used as a kind of transparent canvas. It turned out to be possible when he applied several layers on top of each other and reinforced them with screens in various shades of grey, immediately creating a sort of shadow effect in the work.

Ricardo van Eyk, OPERA (SPURS), 2024, tegenboschvanvreden

A new studio

It wasn't only the materials Van Eyk used that determined the ultimate look of LEVEL, but also a change in his direct environment. Last year, Van Eyk moved into a studio in Nieuw en Meer, a creative hub on the outskirts of Amsterdam near Schiphol. The new space proved difficult to reach by public transport, so Van Eyk decided to buy a car. That changed his perspective on the landscape, he later realised. “In a car, you experience the landscape differently than on foot or by bike. Mentally, you're on a map and you visit stranger places. The work may have originated from that, but often you only realise later how such a change has influenced your work.”

The setup of the exhibition was also influenced by the new studio, which Van Eyk extensively renovated. After getting the practical work out of the way, he wanted to focus on painting. “In recent years, I had mostly been making installations. Now, I wanted to explore materials — what can I do with this material? — and take a break from the overall concept. I also wanted to know if I would be creating a different kind of painting now that I had been making installations for years or if I would pay attention to different things while painting. These works are perhaps a bit more stringent, more refined; there's more happening within the frame. They are more painterly,” says Van Eyk, who chooses his words carefully.

Ricardo van Eyk, Century, 2024, tegenboschvanvreden

A single fluorescent stripe

The gridwork Century is not only a good example of the indirect influence of public space in his work, but especially of how Van Eyk makes material choices. In the bottom right corner, there's a thin, straight stripe in fluorescent orange. It is the only stripe in the exhibition made with spray paint. Graffiti is one of the things you might expect in work that references public space, but Van Eyk makes a different decision. “It’s not the kind of spray paint you see in graffiti. This paint is used to mark road closures. I consciously stay away from graffiti. I’m already working with grids, which could be interpreted as masculine. I don’t want to add a cool graffiti-like element that overwhelms the rest.”

“It took me a long time to realise that I couldn’t use graffiti. In the past, I have used it, but I find the intent less interesting. Making your mark in public space has a rebellious quality, but that’s where it ends. It has a limited, closed meaning. I’ve yet to find a form that transcends the graffiti reference, allowing me to use spray paint as a tool.”

Democratic material

What Van Eyk does find interesting are changes in public space, particularly those that are unintentional, changes that arise from interaction or weathering. For example, a collision with the steel bottom of a service entrance or someone thinking they can quickly paint a window frame and skipping sanding first, leading to a buildup of paint layers that don't adhere properly.

Van Eyk has been working with this since his third year at the academy. It's his go-to material and accumulated and caked-on household paint regularly appears in his work. Van Eyk calls house paint “a democratic material because almost everyone has a can of it somewhere”. Van Eyk’s interest lies in the transformative property of paints. “They have colours that conceal the work that preceded them. I am fascinated by that constant transformation.”

He prefers to work with the ‘dirtiest’ turpentine-based paints, the kind that are hard to find because they don’t meet workplace safety standards. These paints are thick and spread well. Once the layers of paint have become a material in themselves, he cuts into them, scrapes them off and takes an angle grinder to them. In Century, for example, the grid is interrupted by several straight cuts.

Ricardo van Eyk, ACME III, tegenboschvanvreden

Fencing and stucco mesh

Just as he avoided using graffiti, Van Eyk also decided not to recreate dented steel plates from service entrances. He calls these ‘easy strategies’. He continues to work with the same steel plates, but in a completely unique way. “The material goes through a process in my studio, where I make it my own – to the point where I can’t quite control it and it continues to surprise me. If I master the destruction with an angle grinder too well, I stop doing it because it becomes a gimmick.”

In addition to the screens in the OPERA series, another new material in Van Eyk's work is stucco mesh, the kind used in drywall. The mesh is a result of a four-year journey, explains Van Eyk. “I’ve tried everything from tulle and curtains to this stucco mesh.” In the works in the ACME series, he made a drawing on canvas, embedded the mesh between layers of paint and then ground those layers down with an angle grinder, making the drawing partially visible again.

Van Eyk’s fascination with fencing stems from his childhood. As a boy, he found fences enclosing construction sites incredibly interesting. “When you’re confronted with a fence and your view is obstructed by it, you try to see what’s happening behind it.” That’s exactly what viewers do, searching for the fragments of the underlying drawing in an attempt to see the whole picture.

“In Southern Europe, the grids on windows of homes are often decorative, creating a strange tension between public and private,” continues Van Eyk. “It’s a subject I could work with as an artist for years on end.”

LEVEL by Ricardo van Eyk is on view until 19 October 19 at the tegenboschvanvreden art gallery in Amsterdam.

Ricardo van Eyk, LEVEL, tegenboschvanvreden