11 september 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

Preview Unseen: Photographing without a camera – Amanda Means’ everyday titans

For most of us, photography is synonymous with a print made with a camera and a roll of film or SD card. Understandable, but also misleading, because there are other ways to draw (graphy) with light (photo) – even without a camera and film. In fact, since the first half of the 19th century, there have been countless carriers and printing techniques. One of photography’s trailblazers, the Britton William Fox Talbot, discovered that an image would appear if you applied light-sensitive material to paper and placed it in a camera obscura. The American photographer Amanda Means demonstrates that the reverse also works.

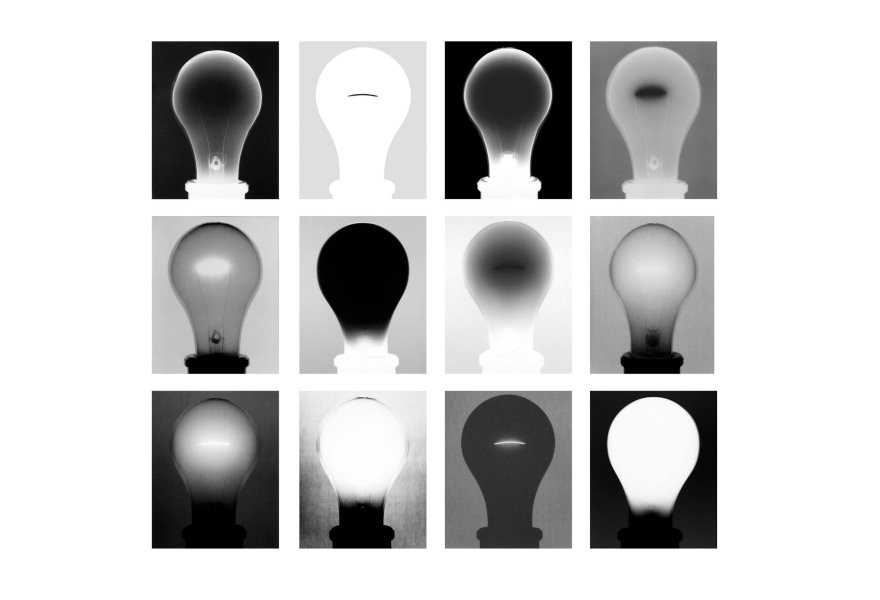

Since the late '80s, Means has been using her own unique process, which entails placing objects—flowers, light bulbs and glasses of water—into a modified 19th-century large format camera. The light isn't captured inside the camera, instead it passes through the object onto light-sensitive photographic paper in the darkroom, causing much more detail to be visible—a reverse camera obscura. The results are razor-sharp enlargements of everyday objects, turning them into everyday titans.

At Unseen, The Merchant House is showing several works from Means’ Water Glasses series and a grid from the Light Bulb series.

Means’ interest in everyday objects goes back to her childhood on a farm in upstate New York. Her parents initially grew fruit, later switching to dairy farming. She developed an eye for subtle shifts and nuances during her youth. “I felt very close to nature, observing the changing seasons and weather, the shifting light on the fields, and in the woods. I remember the feeling I had as a child of being totally immersed in a deep sense of awareness of this world full of life – full of movement, color, shapes, light that surrounded me,” she told us.

After graduating from Cornell University, she moved to Manhattan in 1979. A sharper contrast with her childhood surroundings was almost unimaginable. “There was little that was green. Little that was quiet. Few sounds from the natural world.”

At first, Means did not feel at home in the big city. So, she started taking photographs just outside New York in New Jersey and the Hudson Valley. Little by little, she began to feel more at home in Manhattan and began photographing people on the streets and their shadows. “I began to see a unique beauty in sunlight on city pavement and began noticing the changing shadows in the streets as the sun passed through the sky. Slowly, I began to appreciate and enjoy a very different type of richness in the wild hustle and bustle of Manhattan’s streets – the abounding ambition and energy of its people—people and cultures from all over the world, all packed into one small island!”

“I began looking at Weegee, Gary Winogrand, Diane Arbus, Aaron Siskind, Lewis Hine, Berenice Abbott. It was during this time that I discovered abstract expressionism and felt with great clarity how their work, had evolved out of the energy of Manhattan.” Especially the work of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline deeply moved her. “I began to identify with this work that grew out of New York City—both photography and painting—in a way that I never would have if I hadn’t experienced the city directly. My photographs became more abstract; I photographed machinery and industrial objects close up.”

Amanda Means, Water Glass 70, 2023, The Merchant House

In the mid-1980s, she exhibited her work at Zabriskie Gallery, where she attracted attention with her large prints of landscapes. One of the visitors was Robert Mapplethorpe, who recognized the quality of the prints and asked Means to print his large formats. After that, she worked with Francesca Woodman, Petah Coyne and Roni Horn, among others. But despite having an impressive portfolio, Means was searching for something else.

“As time passed, I got very tired and very bored with this traditional, pristine way of printing. So much of the traditional approach to photographic printing was very narrow. I had mastered it and wanted to explore new ways to work with photographic sensitive materials. I yearned for a more fluid approach and started experimenting with alternative methods.”

Photographing without a camera

At the time, she was already taking photographs of leaves with a large format camera, but was not satisfied with the results. Like Jackson Pollock, she wanted to work from the inside out. The vein structure of the leaves had to be visible. So, she decided to discard the camera and the negatives. From that point on, she placed the leaves in an enlarger and printed them without a film negative, the real leaf was the negative. The results resembled X-rays. Since the images were enormously enlarged, the leaf structure—veins and edges—became very visible. I could take a two-inch leaf and print it forty inches long, making every little detail perfectly clear. This was my first effort with cameraless photography. The leaves were a big success. I was invited to exhibit them at the Museum of Natural History at Harvard University.”

This discovery was liberating for Means. She explains, “The results were spectacular, and I was freed from the traditional approaches that had become so stifling to me.” When she wanted to photograph flowers, Means quickly encountered the only drawback to her invention: it turned out to be impossible to photograph three-dimensional objects. She then converted a 19th-century large format camera into a kind of reverse camera obscura. “I constructed a space inside about a foot square—big enough to hold a large flower—and covered it with a black cloth. This apparatus rests on a box facing the wall. Photo paper is tacked to the wall.” In a darkened darkroom, she projected the light from the device onto paper, then developed the paper like a regular photo, but without using a traditional camera with a film.

Amanda Means, Water Glass 62, 2023, The Merchant House

A burst of radiant light

The series of flowers was followed by a series featuring one light bulb photographed with many different exposures. As there were two light sources inside the device, two different exposures could be made – one with the bulb itself and the other with a bright light behind the bulb. Means experimented with the exposure time and dimmed the light bulb and the back light differently for each shot, resulting in each having different black and grey tones.

“The enlargement throws the viewer’s sense of scale out of kilter. The combination of luminosity and size transforms the image into a burst of radiant light mediated by a subtle range of grays surrounded by an intense darkness The recognizable botanical images depicted within a photograph—flowers, petals, stalks, leaves, and delicate reproductive parts—are transformed from the purely botanical, becoming metaphors for the life-giving quality of light itself to the living organisms of this earth.”

She then followed with a series featuring water glasses filled with sparkling water and ice cubes. These were blown up into gigantic glasses where every little detail can be seen: the air bubbles, the condensation and the lighter core of the ice cubes. “When working with the water glasses, I become deeply absorbed in the remarkable detail in each glass. When I look at these details for a long time and very close up, they become completely abstract and reveal an extraordinary energy of reverberating nuance, shade and texture. During these times, I am reminded of the sensations I had as a child while observing the changing tonalities of light and shadow in the fields and woods on my family’s farm.”

Amanda Means, Water Glass 89, 2023, The Merchant House

A network of ideas

When asked about the connection between her series, Means explained that her work essentially forms a network of ideas, each stemming from her a fascination with light sensitive materials. Means feels visceral connection to the magical way light sensitive materials record life around us, she told us. “One thing leads to another, depending on the outcome of the previous works. I often have the feeling that my work has a life of its own. That it’s leading me in its own direction.” So, it was only logical for Means to move on to light bulbs after the flowers. “To me it’s obvious: light bulbs look like flowers, especially when one considers that both have filaments. I call them the ‘flowers of the city.’”

Means' preference for everyday objects can partly be traced back to her time in New York, but also her childhood, where she developed a keen eye for small changes in her immediate environment. “I’m interested in surrealism and found objects as used in pop art. The tight cropping on my water glasses is influenced by Warhol’s cropping of his soup cans. Also, I love Cezanne’s comment in which he said that there is no need to travel to exotic places to paint. You can paint your stove pipe! He meant that we could find something very beautiful in an everyday stove pipe. We don’t need to depict far-off places and unusual objects. Everyday life all around us is: fascinating, weird, and marvelous.”

She is currently continuing work on a previous series of abstractions. “In these works, I have developed an extremely labor-intensive process of manually folding, refolding, crushing, cracking and then exposing and developing the photographic paper which creates an entirely new three-dimensional terrain of the photographic surface.”

Amanda Means, Water Glass 94, 2023, The Merchant House