10 september 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Sjoerd Knibbeler

How do you make the wind visible? This was a question that photographer Sjoerd Knibbeler asked himself 12 years ago. He found the answer in the exact sciences and since then, has collaborated extensively with scientists. Last spring, for example, he was an artist-in-residence at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, where he spent two months working with a research group studying black holes and gravitational waves. He is currently working on editing the footage he shot there.

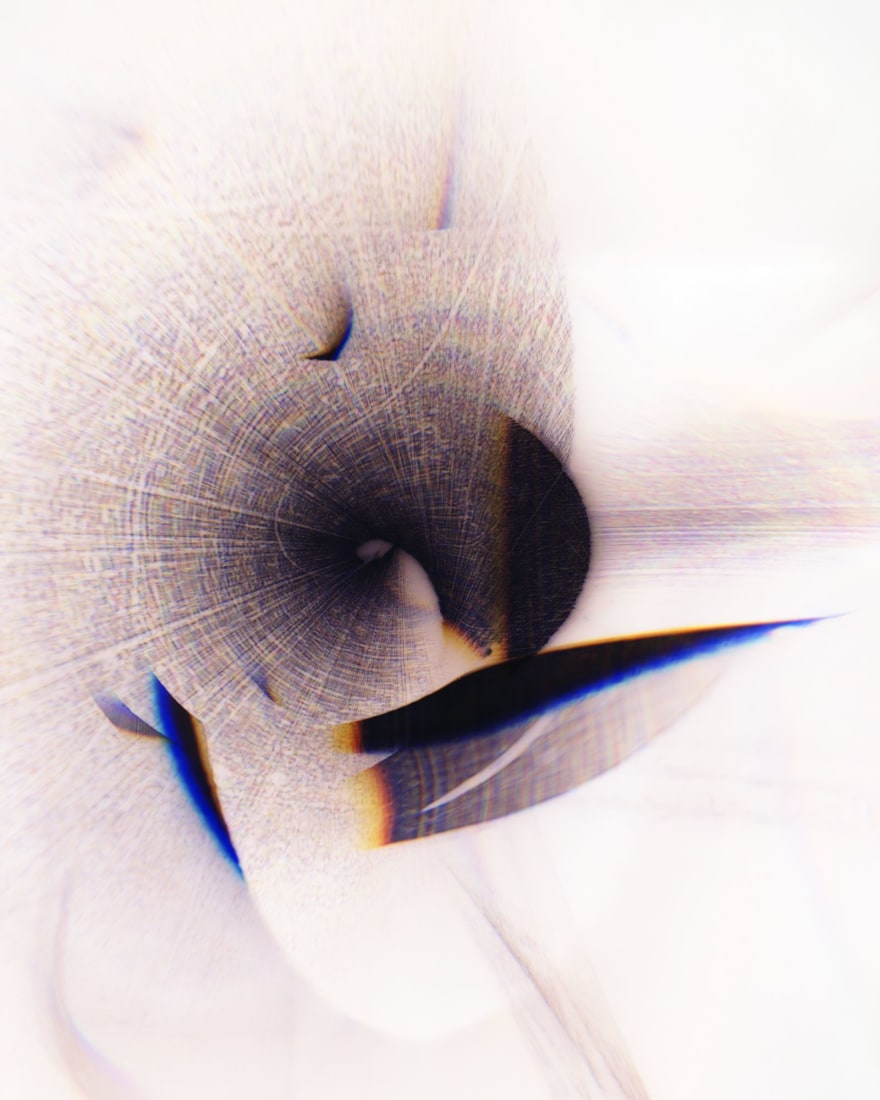

For his new series, Passanten (Passersby), now on display at ROOF-A, Knibbeler turns his attention to the material left behind after the incineration of residual waste. In Delfzijl, he visited EEW's power plant, where waste lies in heaps on the premises. In the power plant, energy is recovered from the waste by burning it in a sustainable way. Metals, glass, ceramics and stone survive the process, but are pulverised in the ovens and mixed with ash into a sort of heavy, grey and black grit. Like a beachcomber, Knibbeler was allowed to wander through the heaps and take whatever caught his eye. Back in the studio, he created sculptures from these materials, which he then photographed.

Passanten by Sjoerd Knibbeler is on display at gallery ROOF-A in Rotterdam from 14 September to 19 October. The gallery will also be showcasing the series at Unseen and Paris Photo.

You’re a photographer, but you create the objects that you photograph. I imagine you don’t only have photography lights, but also quite a few different types of machines. So, what does your studio look like?

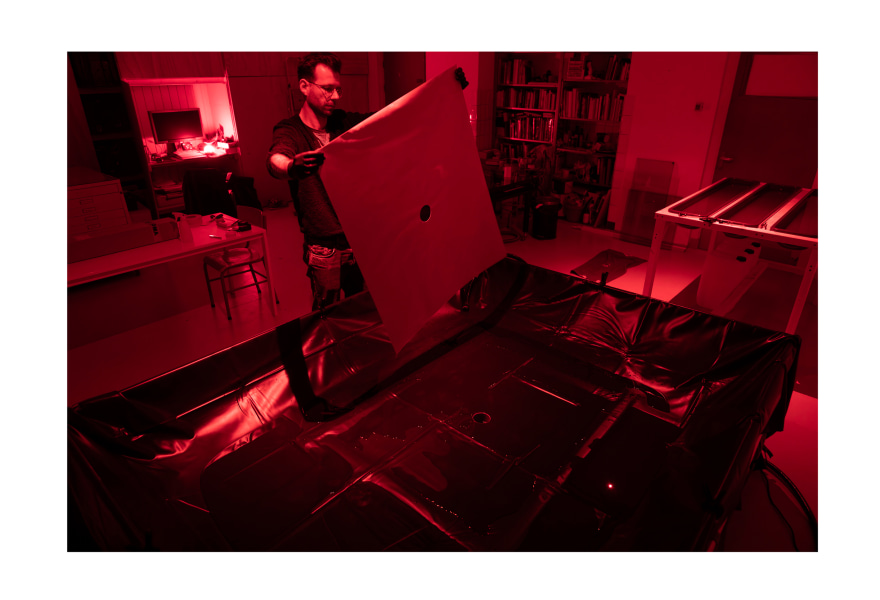

My studio is an old classroom on the ground floor of a former primary school, with views of a lush garden. A large fig tree by the window provides a lot of shade, but enough natural light still comes in through the tall windows. The branches of a rose bush are growing through a crack in one of the window frames and the wall cabinets covering the back wall are filled with exhibition prints, equipment, tools, materials and models. There is a filing cabinet that also serves as a cutting table and in the tiled fireplace where the stove once burned, there is now a bookcase. I use the fourth wall as a background for shoots and keep it as empty as possible, just like the floor space. Tables and cabinets in the space are on wheels, so I can easily move everything and adapt the space however to whatever I need at the time: a workshop, photo studio or classroom for my students. I can also completely darken the room and turn it into a darkroom.

Sjoerd Knibbeler, Passant #04, 2023, ROOF-A

What does a typical day in the studio look like? Do you have routines? Is there music playing or do you prefer silence? And do you welcome visitors or keep the door closed?

I always start at eight in the morning with a cup of coffee. After a quick look at my agenda and email, I try to keep the morning free, so I can work as much as possible when my concentration is at its peak. At the moment, I’m reviewing photos and video material that I shot in April and May during my residency in Copenhagen. The selection, editing and montage processes are mostly done on the computer, but there are also notes, to-do lists, books and sketches lying around that I need for this. It's been years since I last worked with video and I really have to get used to it again. For each work or series, I need to determine the best approach, which means I often have to learn new techniques or refresh my memory. That requires concentration and silence. During shoots or image editing, I love listening to music. Then I can fully immerse myself in the work and keep looking, adjusting, testing, changing and looking again. At such times, I prefer to work alone, but I also enjoy having visitors to discuss work or just catch up on the summer.

Sjoerd Knibbeler, Passant #02, 2023, ROOF-A

You once tried to recreate a tornado and a falling star. Do your projects often begin with such an idea?

My work often starts from a more general, vague fascination with subjects that intrigue me, but that I can’t quite pinpoint. I then start reading about climate science, aviation or geo-engineering, or I visit a research institution or lab to talk to experts and take pictures. Those experiences often morph into ideas.

I think anyone else would immediately dismiss such a project because it’s almost impossible. Why don’t you?

Because it feels fantastic when you manage to pull it off! And especially when you do it together with others. For Falling Star, I worked with scientists and technicians in a wind tunnel lab. Initially, it took some effort to convince them of the value of the experiment. It’s not hard science, of course, but is more about the notion of an idea. But during the first tests, they stopped by to see how it was going and were immediately amazed by what they saw. You can almost see their brains at work and they can explain everything they see. That’s something I really enjoy.

Sjoerd Knibbeler, Falling Star, 2016, ROOF-A

A lot of your work is about technology and science. Where does that fascination with science and technology come from and do you see connections between science and art?

I grew up with binoculars and a microscope, counting birds and scooping up aquatic animals from the pond to study them. I only started using a camera later on, but have always observed things. I think I’ve always had a fascination with magnification: the ability to extend your eye to see things differently and to see more. About 12 years ago, the idea of photographing wind emerged. How do you depict something that is invisible? How do others do it? I ended up in the exact sciences and then something just clicked. A sort of recognition, I think, in the subjects being studied and the questions being asked. That’s what I want to create work about. Since then, I’ve met people from various research fields who share such fascinations, people with enormous ambition and enthusiasm who explore huge, fundamental questions. They may never find the answers, but so many new questions arise in the process, which is something I can totally relate to, haha!

In mid-September, your new show will be opening at ROOF-A, featuring a photo series of steel sculptures placed against a black background on a grey, rocky surface. The sculptures are old technical objects; their previous function is unclear, as is their current one. What exactly are we looking at?

The material that remains after the incineration of residual waste. It lies in large heaps on the grounds of a power plant in Delfzijl, where energy is recovered from residual waste by burning it in a sustainable way. Metals, glass, ceramics and stone survive this process, but are ground in the ovens and mixed with ash into a kind of heavy, grey and black grit. Like a beachcomber, I was allowed to wander over these heaps and take whatever caught my eye back to my studio to work with.

Sjoerd Knibbeler, Exploded view #171, 2017, ROOF-A

What inspired this project?

In early 2022, I was approached by an art consultant through a Berlin gallery friend. She was looking for a Dutch artist for a client. It turned out to be a German company that processes waste into energy: EEW - Energy from Waste. The management team visited my studio and told me about their art programme, for which they invite a photographer each year to reflect on a specific aspect of the company. Three German photographers had preceded me with series created in different plants. Beautiful work, but I couldn’t see myself doing that. Together, we explored other possibilities and I was invited to study the production process on-site. During that visit, my eye was drawn to the large heaps of ash and grit and that’s where the idea originated.

For someone who once wanted to recreate a falling star, this is a fun question: which project would you immediately take on if money and time were not a factor?

For a while now, I’ve been researching how I can capture radio signals from black holes and translate them into an image. Various ideas, strategies and designs have already been considered, but (of course) it turns out to be less straightforward than I initially thought. It would have to be a large installation that serves as both an antenna and camera obscura, somewhere in a remote outdoor location. I’ve already found quite a few enthusiastic, smart minds and handy hands, but extra money and time would be very welcome.

Sjoerd Knibbeler, Passant #19, 2023, ROOF-A

What are you currently working on?

Last spring, I was an artist-in-residence at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, where I spent two months working with a research group studying black holes and gravitational waves. Theoretical physics is very abstract and unfathomable for most people, including myself. But the scientists themselves are very interesting people, as well as the ways in which they work (together). So, I focused my camera on that and now I’m sorting and editing those photos and videos.