02 july 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Wannes Lecompte

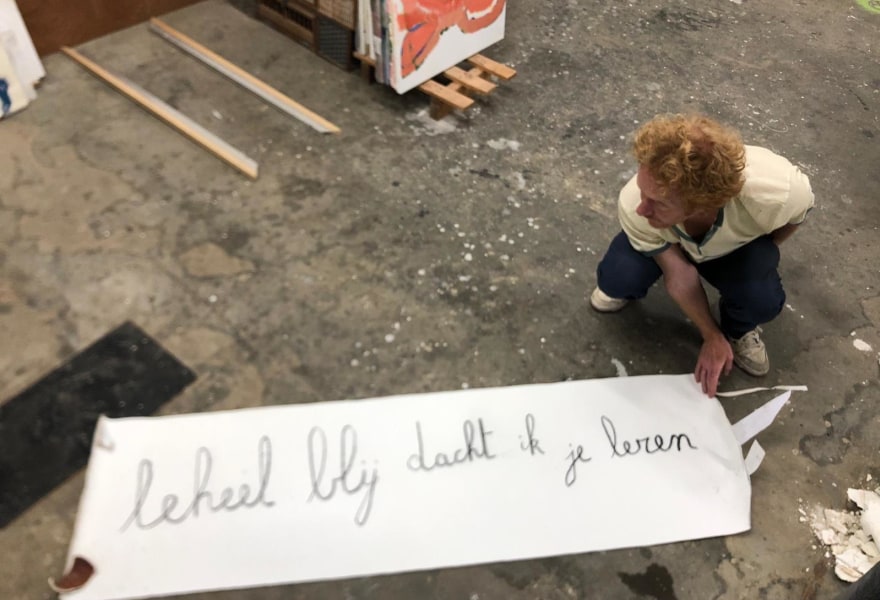

Painter Wannes Lecompte has a motto: Touch and stay away. To him, looking underlies his approach. Lecompte reflects until he sees an efficient way to solve a painting problem. "Look until it's done," he calls it. So, not surprisingly, his work is referred to as slow art.

Lecompte's recent series Symphonic Poems can now be seen at Eva Steynen Gallery in Antwerp. It is a series of work in which he placed the same templates at the edge of the canvas, yet the canvases are each a different size. "Together, the series form a story, a whole. In other words, a whole as a story."

Tiptoe featuring work by Wannes Lecompte and Ken'ichiro Taniguchi, can be seen by appointment at the Eva Steynen Gallery in Antwerp until 14 July.

Where is your studio and how would you describe it?

My studio is located in Werkplaats Walter, a project developed by Teun Verbruggen and Lien van Steendam. It’s in a beautifully renovated building in Anderlecht with a concert hall upstairs and about six studios in the rest of the building. After the adjacent building is renovated, the space will more than double, with more studios and a residency space for musicians. It’s a fantastic place where visual artists and musicians can get together. It's wonderful to work when, for instance, the Flat Earth Society Band is rehearsing upstairs.

In preparation for this interview, I read somewhere that you make 'slow art' in which chance and waiting play a role. How does this translate to a typical day in the studio?

My studio day starts with coffee on the sofa. I take the time to look at what I’ve already done. "Look until it's done," I sometimes say. Then I look for a way, a tactic, to respond to what I see as efficiently as possible. I like the idea that I can do that efficiently. "Arrive and stay away" I like to say. So, to me, looking underlies my actions. And trying to find out exactly what the problem is or where it might be.

Wannes Lecompte, Symfonie in 5 Delen #3, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery

You mentioned the Flat Earth Society Band rehearsing above your studio, but you’ve also collaborated with musicians in the past, haven't you?

I collaborated with musicians for my Different Pieces performances. In this series of nine performances, I invited different musicians each time to join me on stage. Out of deep respect, but also from the ever-intriguing exploration of the intersection between music/musicians and visual art/artists, I served the musicians and washed the dishes on stage. Sometimes, it was more about the action and visual aspect of washing dishes, while other times, the sounds were amplified, creating a noise that served as a foundation for the music.

How do you view the relationship between music and visual art? Is it a completely different discipline or do you view the arts as a whole, as a continuum?

With my Different Pieces performances, I had the honour of collaborating with lots of greats in contemporary improvisation jazz. So, the relationship interests me. What I find fascinating as an abstract painter is that figuration is comparable to melody in music. Remove the figuration and the work becomes abstract because the guide is gone. This is where many people disengage because their anchor is gone. Take melody out of a piece of music and many people get anxious because they 'no longer understand it'. With this in mind, I think it is very important to teach people to look at many other visual and musical means besides melody and figuration. Layering, for example, exists in both music and visual art. "A bit like a woman in winter," a friend told me this week. Beautifully said.

Wannes Lecompte, Symfonie in 5 Delen: #3 appartement, 2024 Eva Steynen Gallery

Congratulations on your duo exhibition with Ken'ichiro Taniguchi at Eva Steynen! Your series Symphonic Poems is on display. The canvases have names like A Symphony in Five Parts, Apartment 3. What inspired this series and is there an underlying idea or did you understand the connection afterward?

Much of my work is created in series because it gives me more opportunities to create variations on one idea, exploring the question: how far and wide can I go with this approach? Whereas other series are often conceived in the same formats, this series was worked on in constantly different formats relative to each other. For the setup, I always placed the same template on each edge, so you see the white open spaces in each work. It looks like a frame within a frame, which doesn't actually exist, as the edges of the works extend to where the edges of the templates are. For the titles of the works, I long debated whether to see them as an 'opera' or 'symphony'. In hindsight, it might have made more sense to refer to opera because each scene is indicated as a place. I find it very interesting how you can subdivide music that takes place in time into spaces that indicate the structure of the music. Together, the entire series is a story, a whole. In other words, a whole as a story.

Since chance and waiting for the composition to reveal itself are part of your method, I imagine the final presentation is less important to you. Is that something you can relate to?

I remember noting the following important sentence: “Stop, because an image doesn't matter”. I like to view painting more as a 'way of doing' than with the goal of creation an image. Recently, I compared it to plants. I love plants. I don't find the aesthetic of a plant important to enjoy looking at it. I am more interested in seeing them grow every day. I think this can be compared to my painting and its significance. As a joke, I sometimes say, “A work doesn't have to be beautiful, but at most well-constructed.”

Wannes Lecompte, Symfonie in 5 Delen: #2 atelier, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery

Since your work is open to interpretation by the viewer, I wondered what the nicest reaction/compliment you've ever received was?

I get unpleasant goosebumps when I only hear that my work is so beautiful. I understand why, but that's not my intention. I'd rather have people intrigued and/or irritated when they see my work. Also, the crucial word 'precise' often comes up when people talk about my work. Hopefully, they mean the precision of my careful, nonchalant approach. But unfortunately, they often mean that it 'precisely' looks like something concrete. Usually, these are insects or creatures (that easily comes to mind once you connect two points). But what I hope for is that they explain how those forms behave. There is a difference between 'precisely a lobster' and 'precisely a lobster stretching after sleep', for example.

Is there a project you would like to work on, but haven't gotten around to for some reason?

I have made three frescoes using the traditional Italian fresco technique, in wet lime. In St. Agatha Berchem, I made the largest of the three on an exterior wall. I would love to do that again. A large fresco where someone else plasters the wall, so I can focus solely on the painting itself. With the experience gained, I feel I could do it even better. The whole process teaches me to think differently about painting and to 'repaint' on canvas afterward.

What are you currently working on?

I am currently reflecting. Since primary school, I have been painting every day. Now, at the age 45, I am thinking about what I have been doing all this time. How meaningful is it to still create 'visually similar work' despite constantly and restlessly thinking differently and therefore always hungry to encounter and discover new things? Currently, I am training my pigeons intensively every day. This training has helped me achieve a very disciplined process. And repeating things every day, I can achieve ever further development of quality that rises ever higher. And how! That can be seen in my pigeons. And in my work? That remains to be seen.

Wannes Lecompte, Symfonie in 5 Delen: #5 academie & untitled, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery