27 march 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Jan Pypers

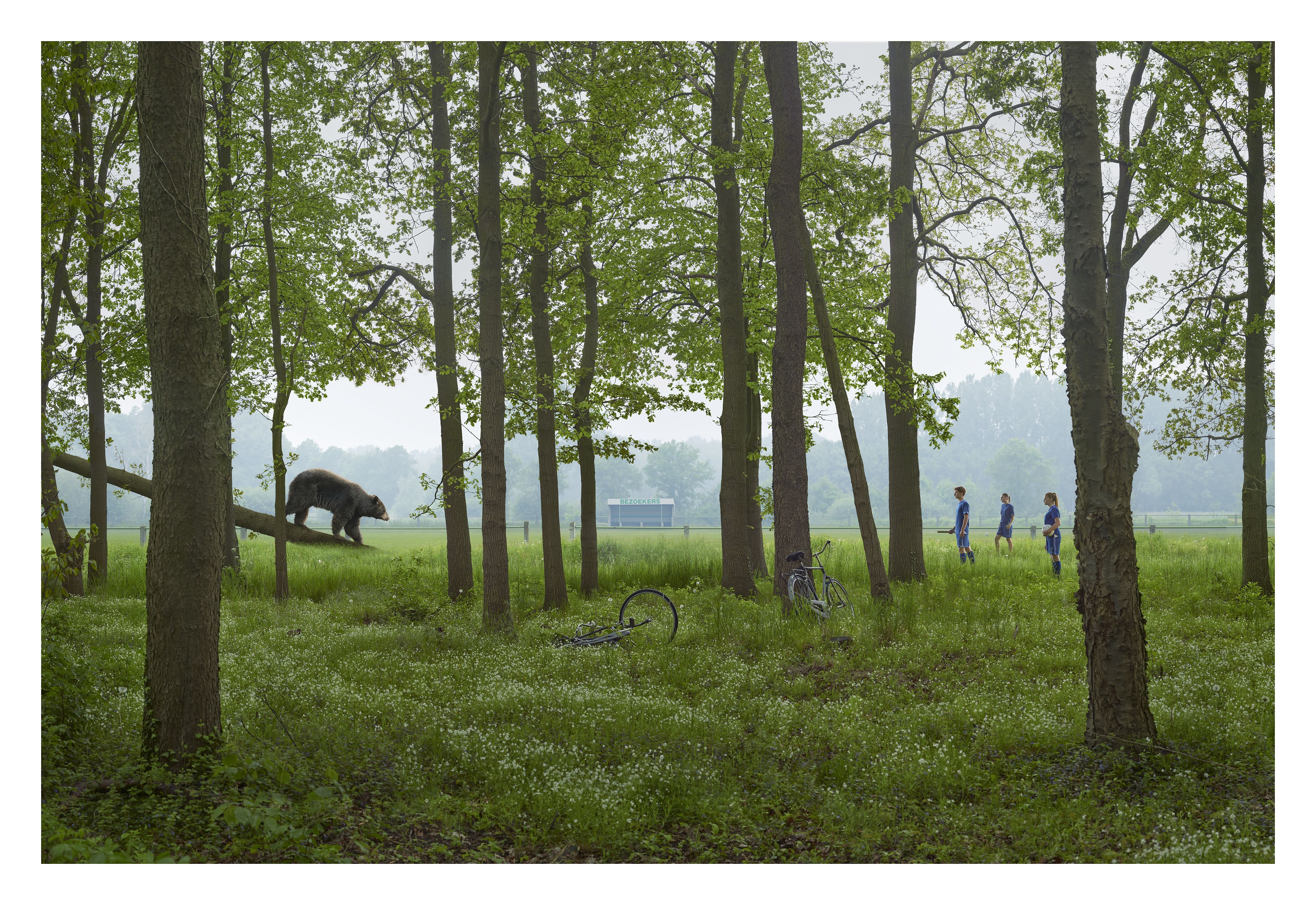

With Jan Pypers’ dioramas, the viewer feels either a bit too early or too late. Something is about to happen – or has just occurred. The two swimmers seated on a crossbeam of a steel structure observe a whale leaping in a bay. They calmly take in the scene. What happened before or after? We’ll never know. In another scene, three scouts gaze upwards at an ibex peering down at them from a rock. The telephoto lens one of them had brought seems unnecessary. Their gaze is not fearful; it's more one of amazement and wonder.

Pypers’ images might prevent this, but it's not very likely. So, they are meticulously constructed by the Belgian artist down to the very last detail. The ability to control everything is Pypers’ only requirement. He doesn't have a typical studio, but creates the scale models in his attic. Larger works are made in the garden or shed.

'Diorama' is currently on display at Contour Gallery in Rotterdam. But this is only a preview, as the Diorama series will eventually consist of about 25 works.

I don't really have a typical artist's studio. For small-scale models, I sometimes work in my attic, but for my larger works, I often work outdoors, such as in the garden, in a shed or under a large tent. Most projects end up much larger in reality than I initially envisioned them.

What is most important to you in a studio: natural light, high ceilings, sufficient storage or friends and colleagues nearby?

With my work, it's important that I can control everything. I almost always work at twilight or at night and I use a lot of artificial light. The best results are achieved when you can combine both artificial lighting and daylight. Unfortunately, the latter is very unpredictable in Belgium. Creating realistic light with artificial light is a huge challenge, but wind is actually my greatest enemy when working on location. That's often a significant limitation because I use long exposure times.

Just very large, to be honest. I actually need a small film studio, but unfortunately, those are unaffordable these days. To compensate, I experimented with 3D and even AI for a while, but so far, I've not been too impressed. Combining photographs with real-scale models yields much better results.

Congratulations on Diorama! In the photos your gallery owner showed me, you're setting up one of the scenes. Should we interpret the title of the show literally?

Absolutely. Dioramas are life-sized three-dimensional display cases showing taxidermy animals in their environment. They were meticulously constructed in natural history museums from the early 20th century onwards to reconnect urbanised people with nature. Incredible depth was created through forced perspective, giving the viewer the impression of being able to see miles through a room. Clever, extraordinarily beautiful, but also artificial.

I use many of these techniques in my work: scale models, artificial light, forced perspective, taxidermied animals, etc.

The theme of Diorama is our relationship with nature and how we are increasingly disconnected from it. Why did you want to address that theme?

We not only encounter these artificial windows into nature in museums, but the old square display cases now have a modern digital version. Like dioramas, social media platforms use visual elements to give us a polished image of reality.

In many ways, modern society is disconnected from nature. With the advent of technology and urbanisation, many people spend less and less time outdoors and more time away from nature in artificial environments. This disconnection has consequences, including a lack of appreciation for the beauty and importance of nature, declining physical and mental health and a diminished understanding of the complex relationships between people and the natural world. It's important for people to find ways to reconnect with nature.

I can't always explain the path to the end result. A memory from my childhood, often coloured, can sometimes be the starting point. But I may also start with a photo or an article in a newspaper about a flooded village or a jogger being attacked by a bear, for example.

Nowadays, I first make a small, simple model and then see what needs to be scaled up and what would be better to photograph in full size. Meanwhile, I keep long lists of focal points, distances, perspectives and lighting plans. This is important to coordinate everything properly during the collage process.

Do computers come into play at any point in the process?

I use fewer computers and digital techniques than most people think. I mainly use Photoshop to clean up things and bring together different images. By the time I sit down at my computer, most of the work is actually done.

The time I spent on Balaena (the water polo players) got a bit out of hand. Often, that's an indication that the project will end up in the trash, but fortunately, not this time. Water and scale models have caused me a lot of headaches, but I am, after all, a child of the sea.

I was immediately intrigued by the tranquil atmosphere of the perfectly stylised scenes. Is that a reaction you often get, that people are immediately drawn to the work?

It’s hard to say, but often people see something completely different in it than what I initially intended. I think my work allows for interpretation and I encourage this. It's as if something has just happened or is about to happen. I try to balance my images on that very moment. Perhaps that's where viewers’ fascination originates?

I’m still working on Diorama. A preview of the first works is now on display at Contour Gallery in Rotterdam. There should be about 25 images in total by 2025.