31 january 2023, Manuela Klerkx

Photographer David Benjamin Sherry: Queering the Landscape

“My work stems from what is often described as climate grief, as many of us are collectively mourning the loss of entire ecosystems. I use photography as a means to understand the world we live in, and communicate with our sacred landscape in new, provocative ways.”

When I asked David Benjamin Sherry (1981, Stony Brook, New York, about the initial reason behind his landscape photography, which can be seen until February 18 in the exhibition Earth Uprising at the Enari gallery in Amsterdam, he resolutely answered “Lily” and showed me a tattoo on the inside of his left wrist of this name. It was 2007 and he needed to spend time alone to cope with the loss of his closest friend, a soulmate named Lily Wheelwright . And where better to do that than in the vast expanses of sand between the orange-red rocks of the deep valleys and raging rivers of the Western United States? Against this spectacular backdrop, the historic and current home of Native Americans, with no more than a camera and a tent, he searched for answers and solace in the wilderness, as many others have done. Eventually he found it – vivid monochrome landscapes born of personal loss and climate grief. An interview with an artist who once referred to himself as a “nostalgic futurist” using a large format 8x10 film camera in order to reflect and understand our connection within the contemporary American landscape.

David Benjamin Sherry, Turn Into Wind, 2022, Enari Gallery

Why are you so fascinated with American landscape photography?

I’ve always been fascinated with plants, animals and the outdoors. I grew up in a small mountain town in the Hudson Valley of New York (Woodstock). Surrounded by iconic beauty in a town built on the idea of artists and the free-loving sixties, liberal and open minded. I had never spent time in the American west as a child. My parents are both working class, first generation Americans whose family’s both immigrated from Eastern Europe. The West was only this idea in my head as a child, where cartoons and movies took place. I was pretty sheltered as a child but had tremendous love and family support. I was taught to pursue my dreams. No one was practical in my family with money or work, and therefore it felt like I had unlimited possibilities to pursue and art was a way to channel my hidden queerness and imagination. Once I went west, I pretty much never returned. I felt like it was a space of invention and freedom… from the known, and from the only life I knew as a child. I began to reconnect deeply to the earth in my mid twenties and my work changed direction.

Where do you think that comes from?

Everything changed after the sudden death of my best friend in 2007. Lily was my best friend for many years and also my support system during the time when I came out as gay and then suddenly, she was gone. I was devastated and suicidal, I felt responsible as many people do when a close friend passes suddenly. To change the course of my thinking and scenery, I ventured out West (California, Oregon and Washington specifically) for the very first time on my own, with my camera. I was around 26 and in graduate school at Yale University where I was getting my masters in photography. At the time, I was using the camera as a sort of visual diary of my personal experiences. And that is where I started taking my first landscape pictures.

David Benjamin Sherry, Eye into the Sky, (Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument), Utah, 2020, Enari Gallery

Didn't you feel very lonely and insignificant in that endless wilderness?

I did feel lonely , but I was grief-stricken and also struggling with my queerness, so I felt I had no choice but to withdraw. But in no time, that feeling quickly dissipates when alone in nature, at least for me. In about 4-5 days, a deeper feeling of connectedness takes over. The fact that we are all alone in this world, ultimately…is a beautiful source of power and energy. Spending time alone in nature is humbling and powerful. If everyone did this, I think the planet would be in a much better place.

What was the effect of that overwhelming nature and loneliness on you?

The weeks I spent there really put things into perspective for me. It was grounding and humbling. Within time, while hiking and exploring I suddenly realized that the beauty and grandeur of nature contrasted with the pain of my grief and that I could only move forward with my life if I surrendered to that nature so to speak. Death and life are all around us if we can see it….If your eyes and mind are open, you can see that it's part of our everyday life and I believe nature is the greatest teacher of this.

What is your approach as a landscape photographer?

Before I start photographing an area, I first do extensive research on it. For example, in my last project “American Monuments'' I focused on all the national monuments that became threatened under the Trump administration. Through my work on this project, I learned about the preservation efforts, political dynamics and natural resource development on “protected” government lands that are intended for the people of the US. With these specific areas the protections were lifted and natural resource development began almost overnight. Just like that, we can lose our protected lands. The land had already been stolen by the original indigenous inhabitants and was being stolen again for the sake of the oil and coal industry. The land that the US protects is vulnerable. If the government decides to lift protected status, the land can be destroyed. Nothing is sacred or permanent.

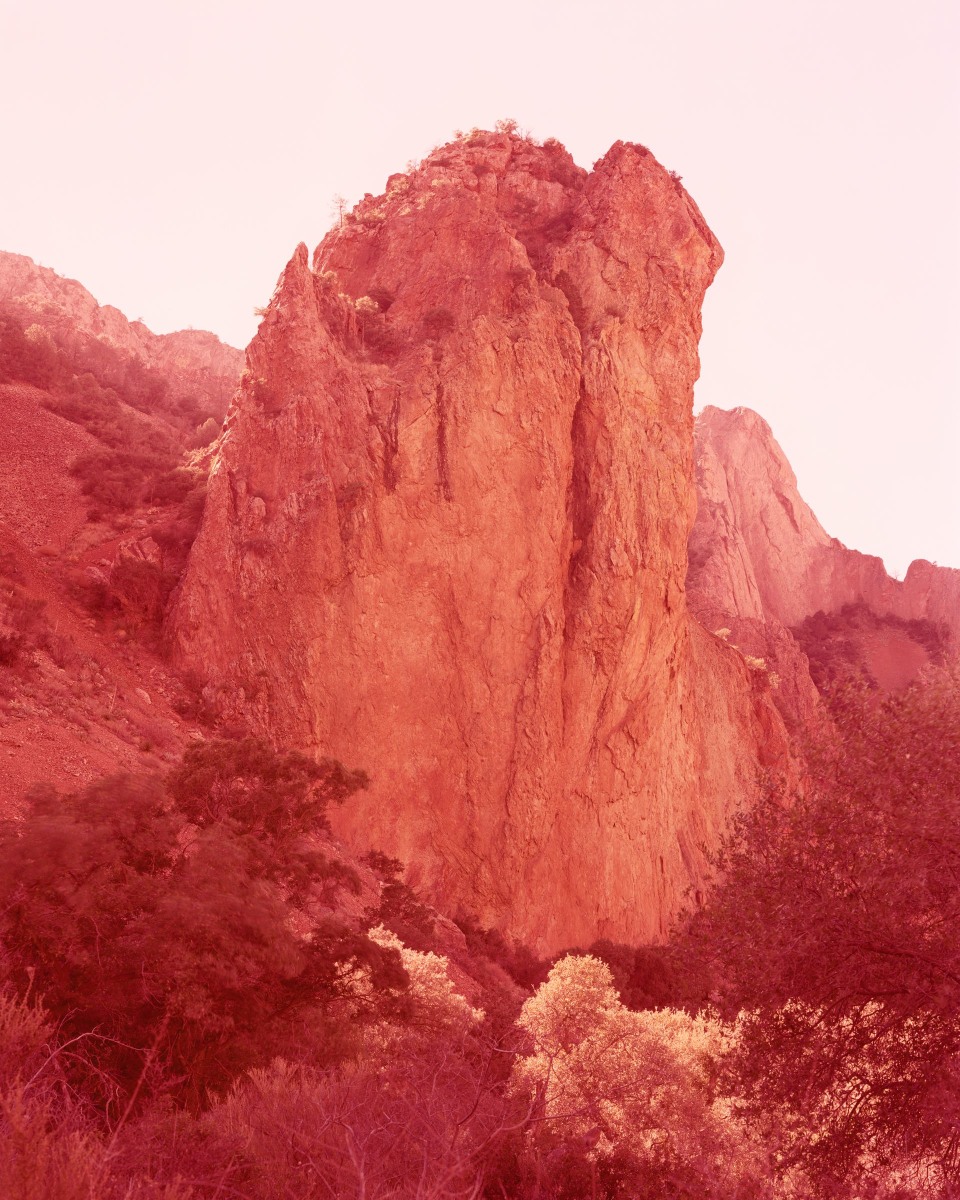

David Benjamin Sherry, Compassion (Chisos Basin, Big Bend National Park), Texas, 2022, Enari Gallery

I can imagine how that knowledge has influenced you and strengthened your conviction to capture these endangered and vulnerable monuments.

Oh, absolutely, and when you do the research and speak with the Native Americans who are taught in their culture to live in harmony with the Earth, you realize how much more they know about living with the land and letting the land be the teacher rather than trying to control it. With my photography, I bring the power of the subject to the surface of the print. The monochrome color is emblematic of this power and gives this landscape a voice or a heartbeat. I try with my photographs to help others “see” the world differently and offer space to resonate with these places. At this point, my work may all be in the US but obviously the Earth is threatened everywhere, and to live in this era of climate change, we all must think about life on Earth drastically differently going forward, which is what my work is meant to help provoke .

How did you make the artistic choices for this series?

In general, my choices are influenced by the history of photography and specifically the landscape photography genre…but also the work is made as a reaction to the idea of Manifest Destiny, which portrayed this land as the promised land that was ripe for the taking by white settlers, despite the fact that there were also people to whom this land was sacred who were already living here.

David Benjamin Sherry, Desire, (Big Bend National Park), Texas, 2021, Enari Gallery

What did you want to convey with your American Monuments series?

When Trump came to power, it was clear to everyone that he would make legislative changes that would be detrimental to protected national monuments and were aimed at personal gain. The more time I spent in nature, the more I realized what we were destroying. The colors I choose for these landscapes represent the spirit and intrinsic value of America's threatened national monuments, the subject of this series of photographs. I focus not only on the beauty of these ecologically and historically significant sites, but also by creating the work and the book and the exhibition of the project, I’m also increasing awareness of the exploitation of this landscape.

You grew up in Woodstock, New York, and were educated in New York City, yet you decided to move to Los Angeles in 2012. Why?

I moved to LA because my time in NYC had run its course. All of my work was being made in the Western US and I felt the romantic notion that if you want to photograph a certain landscape, you must also live there. I couldn't keep traveling back and forth between the East and West Coasts, this felt insincere and I wanted to immerse myself in that western landscape as deeply as possible. Incidentally, it was quite a challenge to adjust to life in Los Angeles. Although it’s wildly beautiful at times, it’s also such an apocalyptic city: with the raging forest fires, drought, traffic, overcrowding, heatwaves, earthquakes…it started adding up for me. I realized I wanted to go deeper into the heart of the Southwest, so I moved after eight years.

David Benjamin Sherry, Silence, (Fajada Butte, Chaco Canyon National Historic Park), New Mexico, 2022, Enari Gallery

You’ve been living in New Mexico since 2020. How do you look back on your time in L.A.?

My time in LA was truly wild. I traveled extensively throughout California and the neighboring western states. I fell in love with the place, the mountains, the deserts, the national and state parks…it's all so vast. I drove so many miles all over the state and I think as much as I loved and romanticized California, I also felt disconnected and like I was drowning in a sea of strip malls. I was overwhelmed and it started affecting my practice. I needed to ground myself in a less populated and less developed area and New Mexico felt like a natural place to go next, since I’d already fallen in love with it on multiple trips over the last decade.

Prior to this interview, you mentioned that anything related to climate change affects you deeply. Can you explain that?

As a human being and as an artist, I am constantly aware of the destruction of the planet. I can’t turn this off. I feel the destruction physically. After spending so much time in nature, you are made aware of the consequences of climate change on a daily basis. I like to be in contact with the earth and see the mountains and breathe the mountain air every day. I like to be around others who feel similarly. In L.A for example, I couldn't sleep well because I was constantly aware of the fact that the city is built on two tectonic plates surrounded by freeways. This fact alone would keep me awake at night! The threats of climate change are everywhere, we live with drought and fires here in New Mexico too. But for some reason it feels safer here for me, the desert is a great teacher and shows time and resilience. There's an optimism I feel in the desert. Others may look at it as a wasteland but to me I see so much life and a sense of timelessness. Humanity may be on the brink of extinction but the land will continue on –the desert shows me this.

What's it like to live in New Mexico?

Moving to the high desert, to New Mexico, has been cathartic for me, it is also breathtakingly beautiful. New Mexico has a relatively small population and low density and you feel that space and distance every day. The light here is beyond anything I’ve ever witnessed. Only after living here day in and day out can you understand why the light is so different than anywhere else. We’re at a very high elevation (7,200 feet) and the air is thin. The weather is very dramatic. In Santa Fe we’re on the very end of the Colorado Plateau and it’s a mountain town. We hike a lot and have a lot of parks and rivers to swim in. It’s heavenly here but the weather can change in an instant…rain, ice, snow and wind. It feels like we’re exposed to the wildness of nature living here. It’s not for everyone but it’s perfect for me.

David Benjamin Sherry, Erasure, 2022, Enari Gallery

What interests you most in photography?

Photography is a strange medium as it’s so closely related to reality, or what we think of as reality. A photograph for me always feels nostalgic as it’s inherently from the past…whether that’s hours or days or years ago. I think photography can be very spiritual and sometimes can feel like a window into the soul, or a window into the world around us. I’ve always loved the analogue process of film photography. It requires patience, even for such an immediate medium. I have always worked with film because I’m interested in slowing down time, in which you are required to simply just watch the light. I love this element of photography the most. My process is very physical. I use a large format film camera and often have to drive for hours down dirt roads and then hike for miles. It's demanding and the exploration and taking risks and making decisions on the fly are all a part of the work that I love. I like being outside, feeling the sun and wind and tasting the desert dust. I print my photographs very large because after experimenting with various sizes, the pictures have a deeper impact and feel more alive to the viewer. They have a physical and often emotional impact. Using scale and color I’m able to depict the emotive force or the capture of a “spirit” of the mountain, the rock, the landscape within the photograph. I believe my pictures are akin to painting, because they’re equally about composition and color as they are about the landscape. I’ve found that with my alternative monochrome printing process, which was born out of color darkroom experimentation, that I’m also re-envisioning how we see the world/landscapes. In fact, the very process of tracing my predecessors' steps, as a queer person, into these iconic wilderness places feels often like a performance… like a queer re-imagining and re-telling of this troubled, beautiful and complicated place. I like to think I’m queering the landscape.

Photography is very spiritual for me as I’ve relied on it to understand my own life, beliefs and the world around me. I believe that when artwork is made under very strict yet playful conditions, after years of repetition…it can conjure a deep power that is inherent to the maker's soul. My artwork is the reason I wake up in the morning and continue to explore my own mind and psyche and continue to push myself to be uncomfortable. It's a belief system and a religion for me, my artwork is my life… and with that said, my soul is displayed on the walls of Enari gallery throughout this month and the stars aligne to bring me to Amsterdam and share this with anyone who chooses to visit the space.