27 september 2022, Manuela Klerkx

Joost Vandebrug: from Rush Hour to the Golden Hour

Joost Vandebrug (1982) was brought up on photography. You could even go so far as to say that he grew up in the darkroom. In a previous life, he was a successful commercial photographer and videographer, spending his days flying back and forth between New York and London. Fortune smiled on him until 2017 when he entered a dark phase of life and realised that the volatility and glamour of billboards, editorials and ad campaigns no longer gave him the satisfaction he needed.

Even the success of Vandebrug’s documentary film Bruce Lee and the Outlaw, which followed a community living under the streets of Bucharest for six years – screened at more than 50 film festivals around the world and winning more than a dozen international awards and a five-star review in The Guardian – could not change his mind. He decided to leave everything behind and devote himself to a personal search for the deeper and darker layers within himself in combination with an in-depth investigation into the technical sides of photography. His artwork includes both conventional and unconventional printing techniques such as pigment transfers and silver gelatin printing on handmade and hand-coated Washi (high-fibre paper from Japan), as well as printing techniques on copper plate and traditional baryta paper.

I interviewed Joost Vandebrug on the occasion of his solo exhibition Exhilarating at Ingrid Deuss in Antwerp.

What is the Exhilarating exhibition about?

About light and hope. The underlying reason is the dark period I experienced in 2017, when I was overcome by fear and secluded myself in my house in the French countryside for months. I had reduced my living and sleeping space to an old chaise longue next to a window. That's where my anxiety seemed most manageable. All I saw through the window was the endless repetition of days turning into nights – from dark to light and from light to dark. Getting out of that state was like learning to walk again, and the four-year journey that followed is what Exhilarating is all about. You might compare it to the story of a bird that wakes before dawn, but trusts that light will come, even though there is still darkness everywhere.

"I need to touch everything."

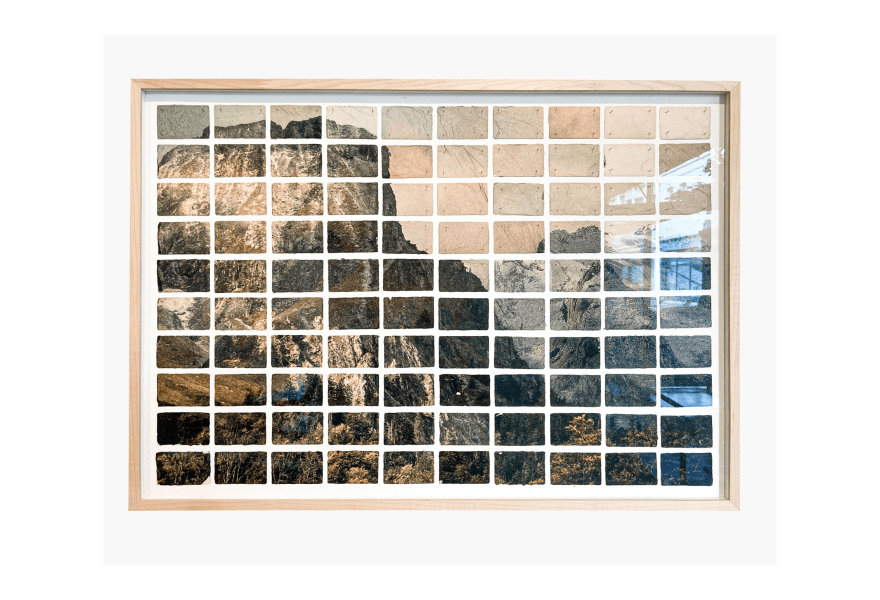

Joost Vandebrug, Exhilarating - E-XII, 2022, Ingrid Deuss Gallery

Where does your love for traditional photography and printing techniques come from?

I would say that the sensitivity and fragility of historical photographic techniques often run parallel to my subjects and desire to embrace any imperfections and 'accidents' as part of the process. I have long since lost interest in the photographic tradition of producing and preserving perfect prints and editions and only use conventional techniques as a kind of frame of reference from which I try to develop new techniques.

How would you describe your work?

My work has a highly technical (pragmatic) and a highly emotional (personal) side. I need both components equally to tell my story.

Can you explain that?

As I mentioned, I experienced a dark period in 2017 that forced me to seek out the light. Because once you are in the dark, the light does not come to you by itself. It’s a process. My work actually shows the phases of such a process step by step. That is why I must and want to touch on every aspect as part of a kind of healing process, remembering the words of Heraclitus: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man.”

Joost Vandebrug, Detail, Exhilarating - E-I, 2022, Ingrid Deuss Gallery

Every work in Exhilarating consists of a hundred small, handmade paper cards, each representing a vast and overwhelming mountain landscape photographed every day for several hours around twilight. The combination of all individual works arranged diagonally shows the full range of these magical golden hours that separate night and day. Each work encompasses a hundred moments in time, each moment unique, yet also part of the series as a whole. So, it's actually about distancing yourself to see the bigger picture. I should add that every moment of light and every moment of darkness was equally important.

In the mountains, in the twilight zone between light and dark,I experienced the overwhelming power of nature.Something greater than yourself.And that is healing.

Joost Vandebrug, Exhilarating, Ingrid Deuss Gallery

Why is it that you are so drawn to the play of light and dark?

I realise more and more that darkness is part of life and can appear anywhere where there is light. So, I accept that the two are inevitably linked – and like as the American poet Walt Whitman (1819-1982) once wrote, are a ‘miracle’. This series is my most personal work to date – from photographing the mountains to the monoprint of the pigments on very delicate paper and the use of thin pins – instead of glue or tape – to keep the works in place. Each step embraces the fragility of the process and the imperfections that can arise, which in turn become an essential part of the end result.

“Every moment of light and dark is a miracle.”Walt WhitmanAmerican poet(1819-1882)

What’s your working method? Do you travel a lot? Do you spend a lot of time in your studio?

I spend six months a year on materials research and travel and six months on personal research. I am interested in how I can use my work to tell what I want to say without falling into pitfalls.

Do you feel that the dark period that started four years ago has ended with this exhibition? Does it feel like a wrap-up?

I realise that I could only take that step back to see the big picture I talked about earlier from a place of positivity and light. After all, it's hard to see the value of darkness when you're surrounded by it. I had wanted to make this work much earlier, but apparently wasn't ready until this year. You might say that my previous work was ‘only’ part of a journey into the light. The realisation that darkness is as important as light does not so much mark a conclusion as a new chapter: towards new darkness and eventually (hopefully!) light again. At least I now know that no matter how dark it gets, there is always a way out. And that's the bliss of hindsight.

Joost Vandebrug, Exhilarating E-XIV, 2022, Ingrid Deuss Gallery