01 august 2022, Manuela Klerkx

Weten wat je ziet: a conversation with writer and publisher Alex de Vries

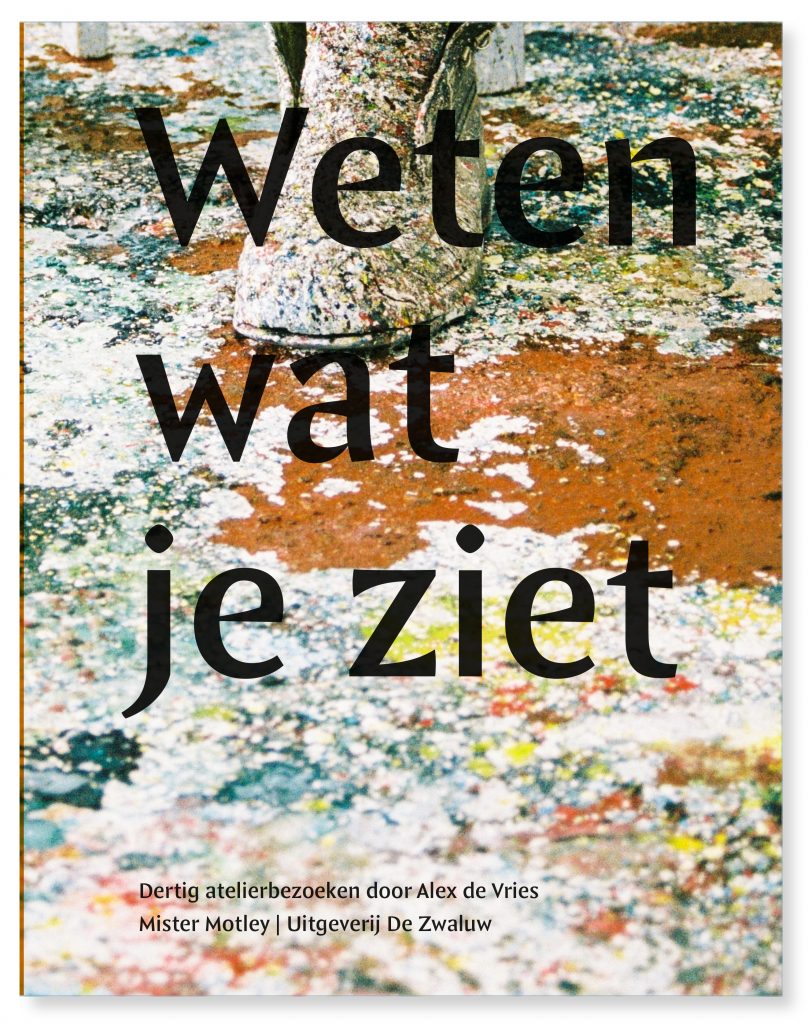

Alex de Vries (1957) is a well-known figure in the Dutch contemporary art world, not only as an art lover and connoisseur, but also as a publisher and writer. Back in 1979, he was co-founder of the art magazine Metropolis M. From 1984 to 1989, he worked at the Shaffy Theater in Amsterdam, after which he was head of communications at ArtEZ School of the Arts Arnhem for eight years. From 1997 to 2001, De Vries was director of the art academy in 's Hertogenbosch. Since 2001, he has been a partner at Stern/Den Hartog & De Vries, a small but highly talented communications agency in The Hague specialising in art and culture. He is also co-owner of Uitgeverij De Zwaluw, which almost exclusively publishes books about visual artists. Weten wat je ziet was recently published, a co-production with Mr Motley. The magazine’s editors selected 30 conversations from a total of 130 studio visits with artists such as Guillaume Bijl, Monika Dahlberg, Kees Goudzwaard, Keiko Sato and Zaida Oenema.

Weten wat je ziet, Alex de Vries, 2022, featuring 30 studio visits, published by Mr Motley and De Zwaluw. Cover photo: Emilia Chinwe Brys.

MK In a recent interview with Metropolis M, Hanne Hagenaars describes you as an ‘art centipede’ and ‘art lover, publisher and writer from day one’. You have written and published extensively about art, ranging from magazine articles to catalogue texts and from portraits of artists to monographs. Where does this love for books and art come from? And how do they relate to each other?

AdV My interest in the visual arts started with literature. At a young age, I had already read a considerable amount and at around the age of 17, I started a literary magazine with my friends Wilbert Cornelissen, Karel Evers and Tom Ordelman during upper secondary school in Arnhem, entitled In Foro. We were inspired by the art critic and artist Maarten Beks and the aging poet Jan H. de Groot, who allowed us to clean out his bookcase and keep any books he had in duplicate. Maarten Beks owned an artist’s book publisher, De Ravenbergpers. This is how I came into contact with the concept of ‘visual poetry’, including the performance duo Robert Joseph and Pier van Dijk. One evening at Robert Joseph’s Poeziehuis, I heard the sound recording of ‘Body Music’ by Marten Hendriks, for which he had punched the outline of his body in an organ book, resulting in a fascinating piece of music. This got me interested in the relationship between language, sound and image and I started studying art history instead of Dutch literature, which I had originally planned to study. In the first volume of Metropolis M, which was created by Rob Smolders, Arjen Kok and myself in 1979, I wrote six articles about publishers and creators of book art.

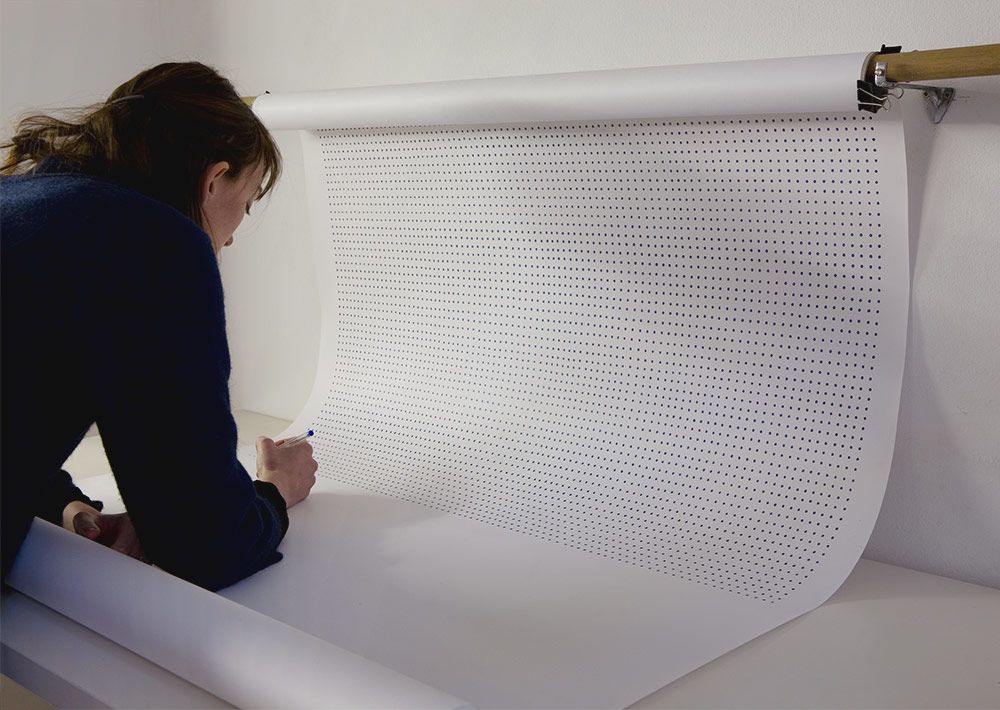

Zaida Oenema, The Perfect Dot, 2011, Galerie Helder

MK In a column on the question of which ten visual arts manifestations you would like to see in a European Canon, you wrote: “The best art is regional art. Regionality causes an experience of reality that takes on a specific form. Within the global perspective of contemporary art, it must be established that every artist lives and works from a region. Whether he comes from that region – born and raised – is another matter, but the artist always understands his immediate living and working environment, even if he leads a nomadic existence.” Could you explain this statement in relation to the contemporary political and social situation in Europe? And what about the relationship between Europe and the rest of the world? Also, can you give an example of this?

AdV Artists are often thought to be ‘out of society’. This has to do with the view that an artist's work is ‘autonomous’, that is, independent and free of outside influences. But in my view, the opposite is true. The artist responds to the world and existence from his or her direct living environment. The artist also has to bike to the bicycle repair shop and bring children to school and go grocery shopping, pay taxes and vote in elections. The work takes shape from where the artist lives and works. In any case, it is always related to what is happening in the world. He or she has to deal with reality just like everyone else – even if the artist, in a social and political sense, opts for an independent idiom in art without reference to events outside the work as such; this is a point of view, a determination of position. Even when not speaking out, you are speaking out.

Lise Sore, Zelfportret met mijn Mens, 2021, O-68

AdV Weten wat je ziet is a selection of descriptions of more than a hundred studio visits since 2015, edited by Lieneke Hulshof and Maurits de Bruijn. What I would like to emphasise with the book is that there are very diverse artistic practices and that no one is inferior to the other. I make no distinction between artists who have achieved international success and artists who are appreciated in a limited circle. According to the assessment criteria of governments, art institutions and funds, an artist’s practice must meet standard conditions to be taken seriously: professional training, active exhibition practice, press reviews, purchases by collectors and museums, representation by a gallery and so on, but ultimately it always comes down to the artist making work that matters on his or her own terms without having to meet any of those criteria. An artist like Guillaume Bijl has no institutional art training, does not have a studio and has created work that, certainly at the beginning of his career, is a negation of the known expressions of visual art, with installations that were accurate representations of, for example, a lamp shop or a meeting room of a political party. In doing so, he has pushed the boundaries of art. It’s about taking something seriously that falls outside the norm and valuing it.

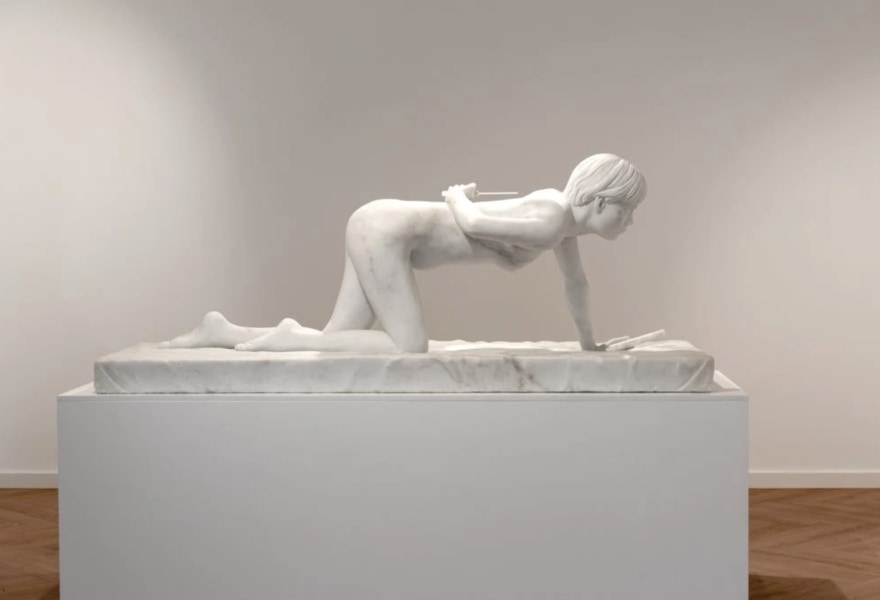

Mark Manders, Working Table, 2017, Zeno X Gallery

MK What do you consider a good work of art? What requirements does it have to meet?

AdV A good work of art does not have to comply with anything. It can be incomprehensible and look awful. It may make no sense to the viewer, either rationally or emotionally. A work of art may cause you to experience it differently every time. You always look at it in a different way, so that you also think about it differently. In 1992, I first saw work by Mark Manders in the hall of the Rietveld building at the art academy in Arnhem. He had arranged objects that I could not relate to each other, but which nevertheless showed a connection for which I could not find an unambiguous explanation. I thought it was the work of a guest teacher who wanted to introduce himself to the students. There was a young man there and I asked him if he knew who made it. It turned out to be him, Mark Manders, and his Self-portrait as a building, a test set-up of his graduation installation. It’s a work I don’t understand, but it grabbed me by the throat all the same. It makes you literally gasp for air. Later, I interviewed Mark in front of an audience on several occasions and it turned out every time that my understanding of his work was wrong in his experience. So, my admiration for his work stems from my misunderstanding of him. I always have to ask myself what it is I am actually looking at.

Monika Dahlberg, 'Sien', 2020, Galerie van den Berge

MK Can you give an example of a book or movie that has influenced your view of art and that you would recommend to (new or veteran) art buyers?

AdV The book Verplaatste tafels (Moved Tables) by K. Schippers from 1969 has strongly influenced my approach to art. I bought it in 1976 and from that point on, I saw everything differently. Schippers notes, for example, that you can look at a box that has been on the table for seven minutes and later at that same box that has been on the table for 12 minutes. What is different and what is the same? The texts and images in it are proposals to view reality as you have never done before. Art does not have to represent reality, but contains a proposal to look at it in a way you have not yet thought possible, when in fact it is very common.

Guillaume Bijl, Sorry, 2022, Keteleer Gallery / Lumen Travo Galerie

MK Which current exhibition should we definitely go see?

AdV Until 28 August 2022, the exhibition Vergaan (Passing) by 91-year-old ‘nature artist’ herman de vries can be seen at the Tot Zover Funeral Museum at De Nieuwe Ooster cemetery in Amsterdam. My partner Jan Willem den Hartog and I collaborated on a book with him, herman de vries – bron, in which he talks extensively about his life and work, with a specific focus on nature. In his own words, he shows nature as art. He told his life story in long conversations with his son Vince, who passed away in 2020. The audio recordings of these conversations can be read almost verbatim in this extensive textbook. For 500 pages, he is extremely candid about what he has done and experienced in life and how it has influenced his work. In Vergaan, he confronts the viewer with the finiteness of existence under the motto ‘when life ends, life goes on, unceasingly’.

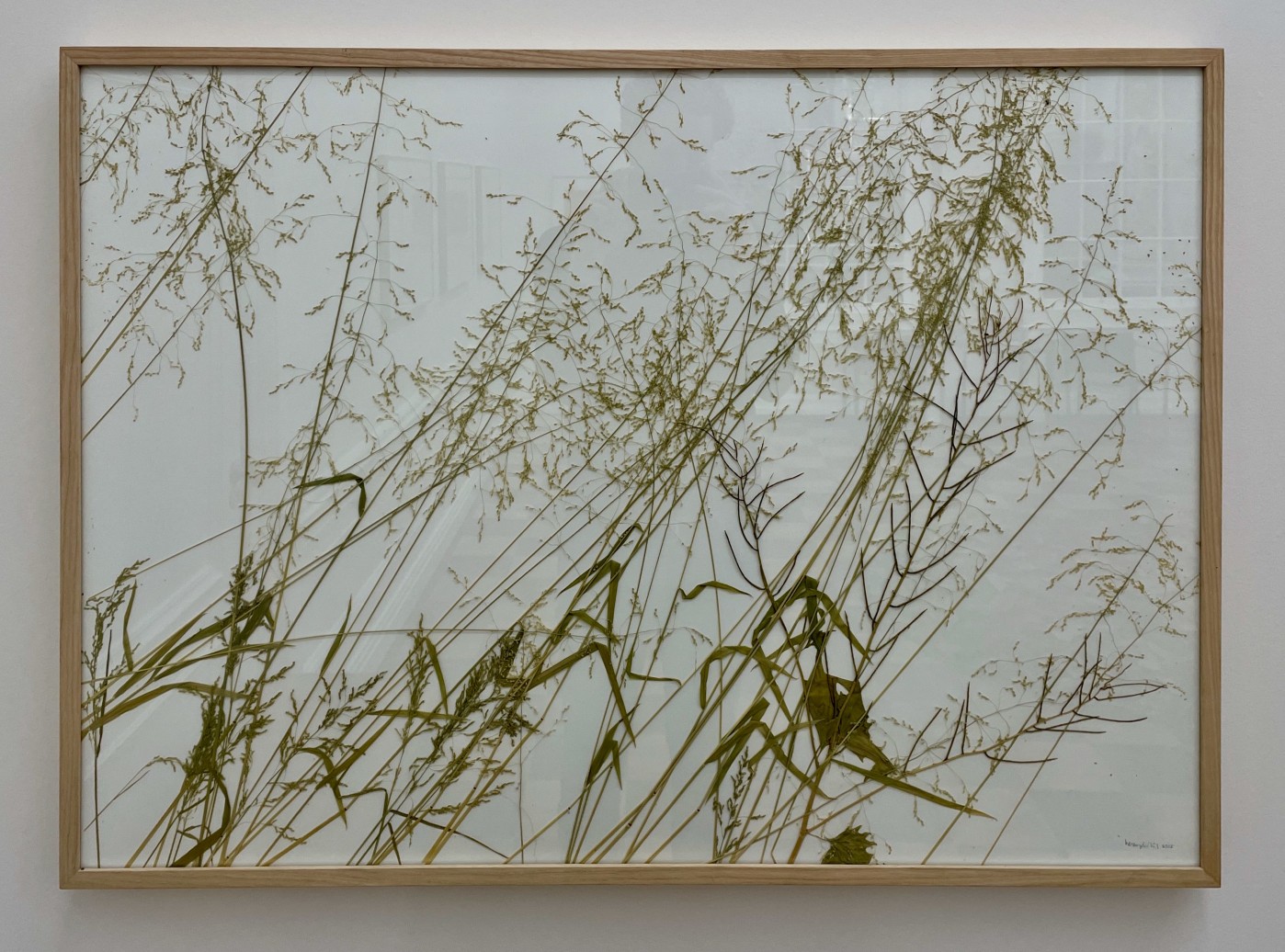

herman de vries, collected: bleiwald 1.6.2015 (milium effusum), 2015, BorzoGallery

Museum tip: Until 18 September 2022 the exhibition 'natura artis magistra' by herman de vries is on display in Museum Kranenburgh in Bergen (NH).