02 may 2022, Flor Linckens

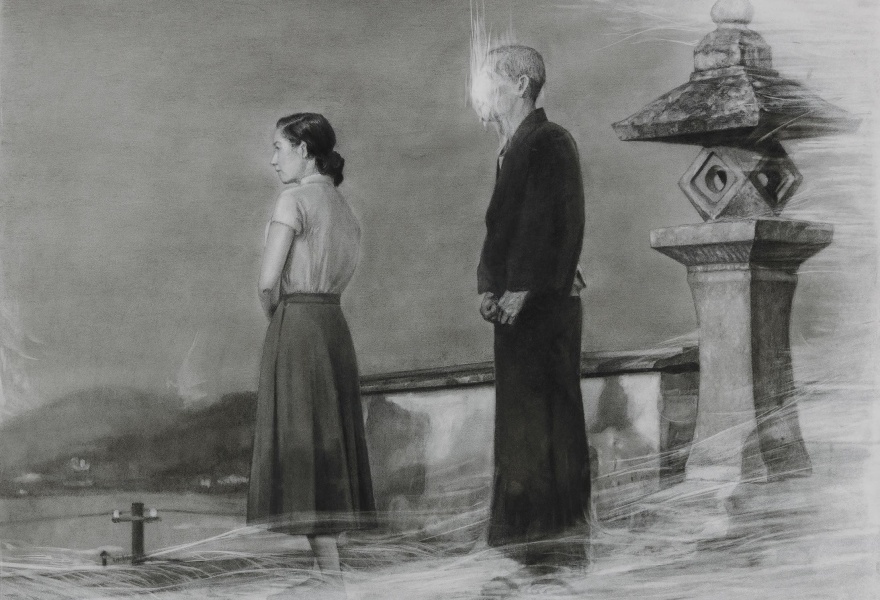

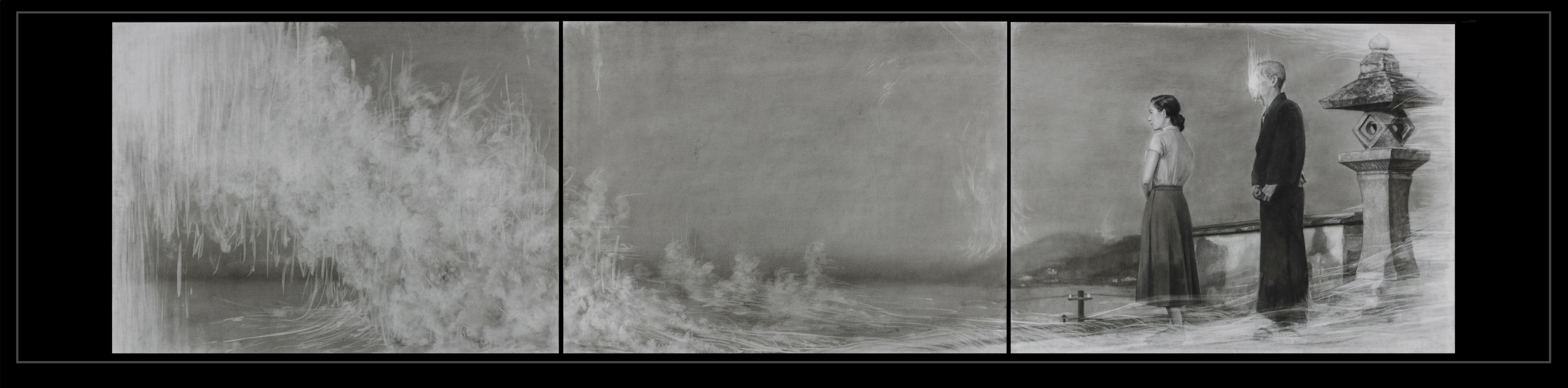

Meiro Koizumi's mist drawings reveal taboos and complexity

Until 28 May, Annet Gelink Gallery will be showing an extraordinary series of fog drawings by Meiro Koizumi, one of the most striking and interesting contemporary Japanese artists right now.

Koizumi: “All my works are about human beings. I think they are very complex and with my artwork I want to deal with this complexity of who we are, how we function and how society functions.”

Meiro Koizumi studied in Tokyo, London and Amsterdam, where he did a residency at the Rijksakademie. His work has been exhibited worldwide, in places like Paris, Haarlem, Tokyo, Sydney, Liverpool, Kiev, Istanbul, Seoul and New York. You can find his work in the collections of institutes like the MoMA, the Kadist Art Foundation in Paris and the Stedelijk Museum. Koizumi exposes certain taboos and social codes that are deeply rooted in Japanese society. He also shows how visual culture and the Japanese view of history - both collectively and individually - are determining factors in this.

Koizumi: “After the war up until recently, we didn’t teach much history in Japan, so we don’t know what our history is. Our parent’s generation, they were born during the war, or right after, so people in Japan couldn’t teach them because the history was too traumatic and they lost the war. So, our parent’s generation, who have been building Japan for let’s say the last 30 years, don’t know much about history. And we are brought up by them. I got the chance to visit different places and now I’m beginning to learn what really happened. It was all taboo and it wasn’t dealt with properly. But our generation has some distance towards the history. We are the new generation who can deal with this, I really believe that.”

In his work, Koizumi tries to capture the layered complexity of people with PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder. He has a knack for contrasting staged and authentic emotion in convincing ways, often with a cynical undertone. For the fog drawings in this exhibition, Koizumi was inspired by the films of the famous Japanese film director Yasujirō Ozu, best known in the West for his film Tokyo Story (1953). During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), Ozu was drafted into military service. His enthusiastic and detailed diary excerpts at the start of the war show that he intended to make war films when he returned home to Japan. But as the head of an army unit that unleashed chemical gas on the Chinese army, he became deeply disillusioned, and ended up directing not a single war film or scene in his career. Instead, he made the scars of the war invisible, using beautiful, serene images and characters that show little emotion (or signs of a roaring inner life) — fitting within the Japanese culture, in which emotions are rarely displayed exuberantly. Ozu was known for barely moving his camera, which makes the camera the defining aspect of the film, rather than the characters. Koizumi: "Depictions of the inner self are stripped down to a set of gestures within a rigid framework.” Koizumi chose to reproduce still images from the film in charcoal, while adding an additional emotional layer. This charcoal mist provides the characters with an extra dimension and it’s a means of reshaping the scars of the past, to make them visible. In doing that, he touches on a certain universality, on a feeling that can be understood worldwide.

For some works, Koizumi connects his line of thinking to more contemporary war situations. In 2019, for example, he showed a series of video works in Eye in which he shows, among other things, the long-term consequences of war. For "Battlelands" (2018), he captured the presentations of PTSD of five American veterans, blindfolded with a GoPro camera. He asked them to walk through their Miami home, while talking about their most traumatic war experiences. Suddenly extremely vulnerable, these veterans talk about Afghanistan and Iraq as you see them walking through their kitchens and the rooms of their children. Koizumi shows how complicated the processing of these problems is, partly because facts, truth, reality and memories become intertwined in the ways in which we - individually and collectively - remember these wars.

Koizumi makes the emotional damage of war tangible and argues that this damage is caused in part because war forces us to function outside of our normal system of norms and values. He exchanges the idealised image of the brave soldier in his work for a more fragile and more damaged alternative. This contrast is often reflected in his work. In Japanese culture, that is highly nationalist in character, the samurai and the kamikaze pilots are glorified. But Koizumi - specifically in his video works “Defect in Vision” (2011) and “Portrait of a Young Samurai” (2009) - wants to highlight their permanent scars. Koizumi’s confrontational video works are meticulously constructed with gradually building emotional tension that bubbles until a boiling point is reached. He confuses and manipulates the viewer, partly through the use of repetition. Koizumi seeks out the viewers' vulnerable spots and uses that tension to his advantage.

Visually, Koizumi refers to both art history (histories) and Japanese film history, but his work is also contextualised by the nuclear disaster in Fukushima in 2011. The artist applies social criticism and asks questions about Japanese ultranationalism, the collective historical awareness (or lack thereof), as well as power relations between state and citizen (like i.e. censorship), but also power relations within families. For the series "Air" (2016), he censored the imperial family from news photos, using oil paint. That was unheard of because that emperor still enjoys a status bordering on the divine.

Koizumi: "My ambition to understand what Japan is all about, what it means to me, how I deal with it, and how I can free myself from it.”