08 april 2022, Wouter van den Eijkel

YAWN HOLDING FIELDS Interview with Indrikis Gelzis | Last 2 weeks

Yawn Holding Fields is Indrikis Gelzis’s second solo exhibition at Tatjana Pieters. Through his compositions of wood, steel and fabric, the Latvian artist raises questions about the effect of incessant processes on the human body. In this show, he makes the connection between yawning and the incessant flow of information that comes our way every day. We asked him how he came up with that comparisson and how he developed his signature style.

Indrikis Gelzis (1988) lives and works in Riga and New York. He graduated from the HISK in Ghent in 2016. Since then his work has been shown in a large number of group exhibitions and he had solo exhibitions at Suprainfinit in Bucharest, ASHES/ASHES in New York, Cinnamon in Rotterdam and at the Latvian National Museum in Riga.

Your exhibition is entitled YAWN HOLDING FIELDS. What does the title refer to?

I will answer your question by quoting a fragment from the introductory text of the show: “Compared to the chest of a body or, more precisely, the parameters of the respiratory system, there is no capacity for the information world and cyberspace. The yawn of the information flow is infinite and ceaseless, with an inability to reach the desired dopamine mark”.

As a reflexive process, yawning brings a brief satisfaction and calmness to the human body, and as an involuntary act it is very catchy to the ones witnessing it. Whenever I yawn or I feel a desire to scream, I like to imagine experiencing bodily processes in a transcendent way. To have a deep, magnetic, constant and never-ending inhale or to scream persistently without needing to take a breath. With the title of the show I was aiming to describe a state of continuity and transcendence, contrary to the limited capabilities of the human body and its parameters.

Usually, yawning stands for boredom, but not in this case. Can you tell us what you refer to?

It's a very natural response to being tired, yawning is usually triggered by sleepiness or fatigue. I think a lot about inexhaustible phenomena such as sunlight, water, tidal energy, I compare these processes with the flow of information - it helps me to imagine and create a rhythm of lines and shapes in my work. The technological revolution has brought information to the fore as both a source and an instrument of power. With this title I don’t necessarily refer to boredom, but I rather question exhaustible and inexhaustible processes in relation to the human body, technology, data, labour, the corporate world and so on.

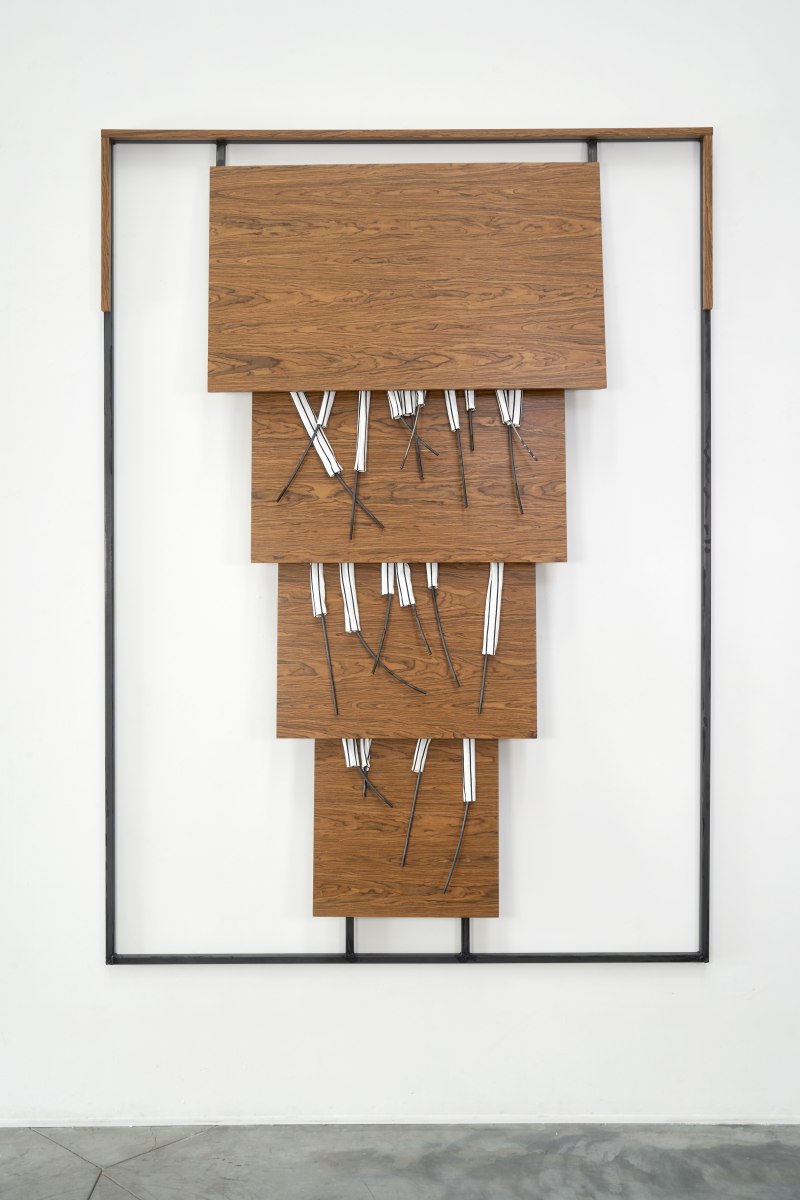

Indrikis Gelzis, Screaming Throat, 2022, TATJANA PIETERS

You compare our current computer networks to a human respiratory system. How did you arrive at that comparison?

I think a lot about the digital and technological processes that are based on anatomical possibilities of the human body and how it is increasingly outperforming us. I don’t compare computer networks to anatomical systems alone, my practice is based on certain aspects and the visual methods of infographics, in particular, how the information has been processed, analysed, compared and how it describes society or other phenomena as a whole. Think, for example, of the stock markets, or the novel and exciting means Facebook innovates to profit off its users’ data. Like the human respiratory system, these processes feel very fluid and lifelike to me.

In the press release you cite the popular philosopher Slavoj Zizek who dubs man’s presence an ontological catastrophe. Why did this particular statement resonate with you?

The quote was about the human subject as a unique tear in the fabric of the universe, a case in which something has gone terribly wrong. According to him, the appearance of the human subject is an ontological catastrophe. By using this quote I don’t necessarily share the same belief system, it rather helped me to give a context and to emphasise the current state of my mind.

Also, in this world view, what is man’s place in this world?

To me it is important to keep the content of my work as open as possible and to hold the values of equality, democracy and liberty. This serves as one of the main reasons I have never depicted a human head or face in my work. The headless figures that appear in my work communicate with body language, gesture, posture or through anatomical systems translated into the lines, shapes and forms. My aim and artistic strategy is focused on creating a universal visual language that fulfils its purpose and meaning in different contexts.

Indrikis Gelzis, Limbs between non-stepping stairs, 2022, TATJANA PIETERS

Your work current series at Tatjana Pieters touches on quite a few current themes. The pandemic, man’s increasing dependency on technology and transparency of information or the lack thereof. Can you explain how these themes are related?

I don’t express my opinion through my work, I see myself as an observer of current times, of the world that surrounds me and, in particular, my experience as an emotional and sentient participant of it. In my view, with every novel technological invention the notion and the sensation of the living and anatomical body is becoming increasingly more sensitive and fragile.

I like to imagine the infrastructure of the information world, the way it is weaving throughout the earth's crust and the urban and rural buildings, stretching along highways, flowing through the air and connecting not only the sky to the earth but also people's minds through various technological devices. To quote the final sentence of the introductory text of the show: “Information wires turn into blood vessels. Blood vessels turn into information wires.”

As I was mentioning before, information is being used as an instrument of power (national, political, business related, cultural, etc.) and now when society is being integrated into the cyberspace as a more permanent participant and becoming increasingly more dependent on the digital devices and its services, it feels to me, that the sensitivity of information is at its highest peak. Our minds are exposed to new methods of influence and control by, first of all, how we experience our daily lives and the world around us and by, second of all, and, more importantly, how it affects our belief system and what we accept as truth.

Once you’ve seen a work of yours it’s hard to confuse it with someone else’s work. In other words, you have signature style. How did you get there? Are there any artists you feel related to/that inspire you?

The very first work I made in this style was back in 2016 and it’s titled “Portrait of parallelism”. Back then I was studying at the HISK - Higher Institute for Fine Arts located in Ghent, Belgium. These were two significant years that completely changed my views and understanding of art practice and art world. More importantly, it was quite an ideological contrast with the education I obtained at the Art Academy of Latvia.

The time spent studying at the HISK allowed me to better understand myself and the cultural heritage that had formed me as a person. As a result of a yearlong research and quest for references and new inspiration, I found myself being curious about the visual and ideological qualities of graphs and charts and the information world. While researching these subjects I was lucky to find an essay “Computational Infrastructure and Aesthetics” by Nick Srnicek. Another important essay to me is “Non-Correlational Thought” by Steven Shaviro. I was reading about speculative realism and object-oriented ontology, a philosophy by Graham Herman. To name just a few of the sources of inspiration, these were the triggering points that shaped my thinking process, formed a logic and helped me to develop the visual language that I still perfect today.

I’m very interested in figurative painting and, to be honest, I have felt a strong desire to paint for many years, but I’m keeping myself faithful and dedicated to the visual language that I have created over the years. I vividly remember seeing some paintings by Mark Rothko at the National Museum of Latvia when I was a kid. It left a great impression on me.

Indrikis Gelzis, Mealy Mouth, 2022, TATJANA PIETERS

You made this series during the pandemic and possibly during a lockdown. Did the pandemic impact this series and if so how?

The works included in this show are covering the last 16 months of my studio practice, so yes, this exhibition was created during the lockdown. Personally, the whole experience of being both socially and physically isolated turned out to be a very informative and highly productive period of time. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Covid has taken more than 6 million lives worldwide. That is an unbearable extent of pain and sorrow, I felt and I still feel empathy for the people who lost their loved ones and for those who are still in the battle for their wellbeing. This experience gave me a deeper understanding of how valuable, fragile and unpredictable life is.

Can you explain how you incorporated these themes in one of the works in the exhibition?

There are stages in my practice when I arrive at more or less important shifting points, and in this case I feel that “Screaming throat” is one of them. While creating this work I was using a slightly different set of logic and organisation. Instead of incorporating or depicting an entire headless figure or a gesture of a hand or a leg, I was repurposing these lines in order to capture a motion of a scream, and the structure of this work is based on the anatomy of a throat. My dear friend Jacquelyn Davis once wrote about my work and I quote: “Dreams become drafts become models become proposals become reality”, I will add - lines become information become gestures become throat become scream.

What are you currently working on? Is it thematically related?

At the moment I’m back in Riga, Latvia and I’m focusing on developing new digital models and in the meantime I'm executing a rather complex piece on a larger scale. Together with Tatjana Pieters and Suprainfinit gallery we are working on my first monograph made in collaboration with the graphic designers Vincent Vrints and Naomi Kolsteren. We are aiming to have the book launch in early June, 2022. In the middle of August I’m moving back to New York for an indefinite period of time.

Indrikis Gelzis, Soft Cage, 2022, TATJANA PIETERS

Yawn Holding Fields by Indrikis Gelzis is on display at Tatjana Pieters through 17 April 2022