16 september 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

The Shroud of Turin, one of the most mysterious and controversial relics

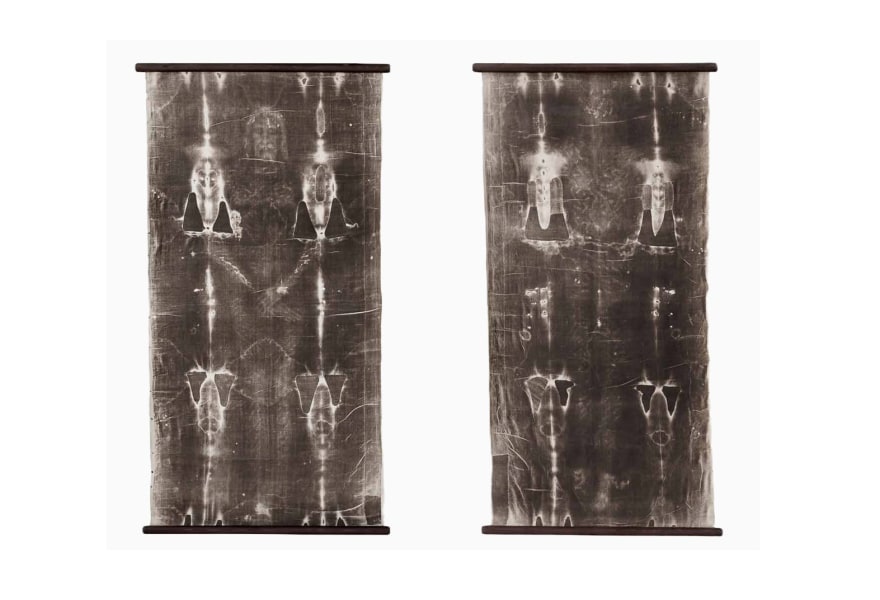

Chances are you’ve seen an image of the Shroud of Turin before. Far less certain is that you've seen this image in life-sized format. Only two copies of the life-sized version of Giuseppe Enrie's photographs from 1931 are known: one is owned by the Institut Catholique Paris and the other can be seen at Unseen at the Depth of Field stand. We spoke with Joris Jansen from Depth of Field about the carbon prints of the front and back of the martyred Jesus Christ—or is it Leonardo da Vinci?

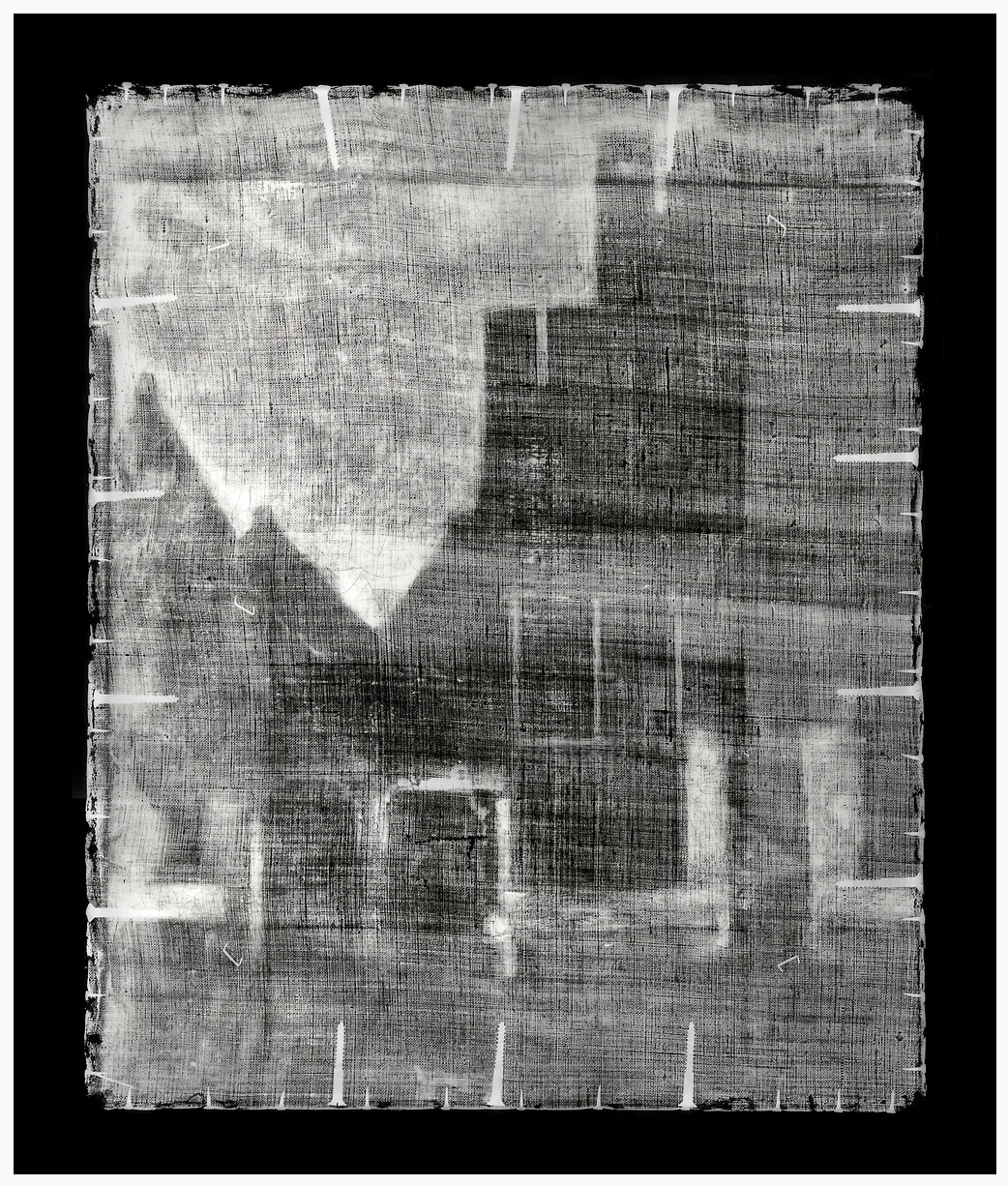

The fairly new Amsterdam gallery Depth of Field is taking part in Unseen in the new Past in the Present section. “At Unseen, we’re showing 1:1 reproductions of artwork, but there's always something more or different that can be seen in the photos than in the original. Take the shroud, for instance. It’s printed as a negative, which reveals the image of Jesus. In Rene Gerritsen's X-rays of paintings, you can see through the entire object: fabric, muscle framework and mounting screws suddenly become visible. And a photo of Oscar Schlemmer's painting has only survived thanks to photography, as the original was destroyed by the Nazis as ‘degenerate art.’”

‘Het straatje’, Johannes Vermeer, ca. 1658 Rontgen photography by Rene Gerritsen

Photographer Joris Jansen founded the gallery during the pandemic together with his business partner, art historian Wendela Hubrecht. The duo focuses on photography from the 19th and early 20th centuries with a focus on unique high-quality works. They are especially drawn to the stories behind the pictures, Jansen tells us in his Amsterdam office. This is certainly the case with Giuseppe Enrie's photos.

In 1934, at the request of the Catholic Church, Enrie photographed one of the world’s most controversial relics: the Shroud of Turin. The remarkable thing about the shroud is that when photographed, a negative image of a martyred man appears. The shroud is not just any relic, of course, but inextricably linked to one of the most important passages of the New Testament: the resurrection of Christ after his crucifixion. Normally, shrouds are buried along with the body, but the fact that this cloth was preserved is, for believers, tangible proof that Christ rose from the dead. For a devout Catholic, the Shroud of Turin is therefore a relic of great significance. Curiously, the Roman Catholic Church has never officially recognised the shroud.

High Da Vinci Code appeal

Enrie was not the first to photograph the shroud. In 1890, lawyer and amateur photographer Secondo Pia took pictures when the shroud was exhibited on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of Turin Cathedral. “It must have been miraculous for Pia to suddenly see a man when he developed his negatives. What makes the shroud so interesting is that it's essentially a negative avant la lettre,” Jansen continues, “Negatives as we know them from photography did not exist yet. Even the notion of a negative did not exist. I wonder how someone came up with the idea of making a negative without knowing about photography.”

Pia’s images were not of sufficient quality to serve as definitive proof. But they sparked new interest in the shroud and prompted considerable research. So, in 1931, the Vatican asked Giuseppe Enrie to take professional photographs. The prints displayed at Unseen were made by Enrie in 1934.

Unfortunately for the Vatican, even Enrie's images did not provide conclusive evidence, leaving the shroud surrounded by mystery. It remains an object with a high ‘Da Vinci Code’ appeal, as science also finds itself at a loss. This mystery likely makes the shroud even more intriguing.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (National Gallery, London) Adolphe Braun, c.1870-1895

Is it Leonardo?

In sindonology—the study of the shroud—almost everything is debated, from its authenticity to the chemicals used and from the type of fabric to the places where the cloth has been located. There are roughly two schools of thought: the first believes it’s the authentic shroud, while the second thinks it's a late medieval forgery.

The first group points to traces of embalming, herbs, a special energy released during the crucifixion or a Maillard reaction. The spots where this reaction occurred are exactly where the image is visible. The second group attributes it to specific individuals and creators. One theory claims that Leonardo da Vinci created the shroud using a magic lantern and chemicals that were available at the time. Da Vinci allegedly believed that the church held too much power and made the shroud to mock the belief that Jesus rose from the dead. He could have used one of the corpses he studied for his anatomical research and the face could be Da Vinci himself. The image on the shroud closely matches the face of Jesus in Salvator Mundi, a painting attributed to Da Vinci.

More likely, however, is that the shroud belonged to someone else, more specifically Jacques de Molay, the last leader of the Knights Templar. De Molay was tortured on the orders of Pope Clement V in 1307. His body was reportedly wrapped in a cloth for 30 hours in a comatose state to recover. After De Molay was executed, the shroud ended up in the possession of the uncle of a fellow executed Templar, Geoffroi de Charny, whose widow was the first to exhibit it.

Silence

There is a moment of silence after Jansen unrolls the life-sized carbon print on the floor of his office. Before us lies Christ in full. The signs of torture are clearly visible on the print. You can see where the crown of thorns was placed on his head, the wounds on his hands and feet from the nails and the marks on his back from the scourging.

Although I’m not religious, and despite the Shroud of Turin being surrounded by mystery and speculation, the idea that I might be looking at the body of Christ, one of the most significant figures in Western history, or at another man who met a gruesome end centuries ago, is enough to leave me speechless.