Connexion

S'inscrire

FR

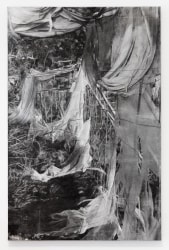

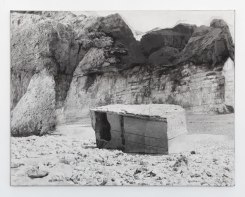

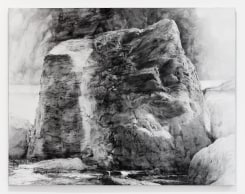

In her work, Marie Cloquet likes to move from the center to the periphery, her eye is drawn to destruction, marginalization and the abject. Years ago, while traveling through the West African country of Mauritania, she became fascinated with Nouadhibou. In this coastal borderland town, Cloquet discovered ‘a world under the radar’, which had clearly been deprived of the benefits of globalization. Slavery, beached shipwrecks and other debris, traces of (neo) colonialism and refugees stranded after a failed crossing to Europe: Nouadhibou, no matter how unknown and far away, is a scale model of current world issues. How do people live (survive) here? Is there harmony in the chaos? How does man deal with places, events or objects that are eyesores that present themselves as virtually ineradicable?

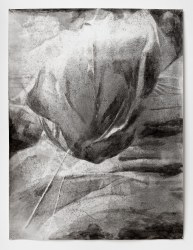

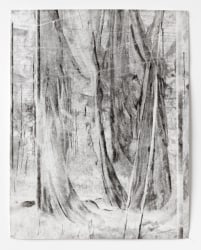

Cloquet put together an extensive archive of photographs that she made in the coastal town, and uses it time and again to create her monumental landscapes on canvas. She considers the images, both digital and analog, as sketches and sees similarities between her process and that of classical painters. Similar to the way in which, for example, the Flemish masters arranged the sketches they made on site, once back in their studios, into new, realistic looking compositions, Cloquet cuts up and mixes her images into independent entities that remain only loosely connected with the real world. After manipulating the photos in the darkroom, she prints them on drawing paper, tears them up and reconstructs them collage-wise, using watercolor paint. The rugged, anonymous worlds that emerge, play with scale, size and perspectives and simultaneously appeal, as places of devastation, to our collective memory; familiarity and alienation, attraction and repulsion come together in the viewing experience.

More than ever, it is the experiment that drives Cloquet’s work. If initially her pictures, mainly because of the analog production method, remained confined to the black and white spectrum, the artist has recently begun to gradually introduce color in her work. Subtle, pale and sketchy, so that the works, somehow reminiscent of tapestries, tend towards the realm of the suggestive. Through her production of photograms, in the spirit of Man Ray, Cloquet also explores for the first time the domain of camera-less photography. By placing and exposing objects directly on photosensitive material in the dark room, she creates highly aesthetic images of graceful contours, complemented with transparent forms. It is an attempt to place a gentle veil over dramatic footage, to cover confrontational facts on the current state of the world and the human condition with a layer beauty. Do we undergo these depicted obstacles in a different, more open manner? Can beauty and the repulsive exist simultaneously and feed each other?

Cloquet does not speak in symbols, but rather in images. Nevertheless, her visual motifs are imbued with an emotional charge, an indirect reaction to the impressions that reach her as an artist and a human being in the 21st century. A torn and grubby curtain, a makeshift, patched together, living hut: they depict a broken homeport, a destroyed shelter – something man has a dire need for in times of chaos. At the same time, Cloquet refers to motifs and genres from art history: the draperies in classical painting, for example, or the abstract forms of Constructivism. Broadly referencing photography, painting, (non-)architecture and sculpture, Cloquet’s works seem to transcend boundaries and, in their own way, make a bid for the notion of ‘total work of art ’. They are inclusive in the way they manage – if only for a moment – to elude extremes such as here and there, then and now, and I and the other.

Grete Simkuté

Cloquet put together an extensive archive of photographs that she made in the coastal town, and uses it time and again to create her monumental landscapes on canvas. She considers the images, both digital and analog, as sketches and sees similarities between her process and that of classical painters. Similar to the way in which, for example, the Flemish masters arranged the sketches they made on site, once back in their studios, into new, realistic looking compositions, Cloquet cuts up and mixes her images into independent entities that remain only loosely connected with the real world. After manipulating the photos in the darkroom, she prints them on drawing paper, tears them up and reconstructs them collage-wise, using watercolor paint. The rugged, anonymous worlds that emerge, play with scale, size and perspectives and simultaneously appeal, as places of devastation, to our collective memory; familiarity and alienation, attraction and repulsion come together in the viewing experience.

More than ever, it is the experiment that drives Cloquet’s work. If initially her pictures, mainly because of the analog production method, remained confined to the black and white spectrum, the artist has recently begun to gradually introduce color in her work. Subtle, pale and sketchy, so that the works, somehow reminiscent of tapestries, tend towards the realm of the suggestive. Through her production of photograms, in the spirit of Man Ray, Cloquet also explores for the first time the domain of camera-less photography. By placing and exposing objects directly on photosensitive material in the dark room, she creates highly aesthetic images of graceful contours, complemented with transparent forms. It is an attempt to place a gentle veil over dramatic footage, to cover confrontational facts on the current state of the world and the human condition with a layer beauty. Do we undergo these depicted obstacles in a different, more open manner? Can beauty and the repulsive exist simultaneously and feed each other?

Cloquet does not speak in symbols, but rather in images. Nevertheless, her visual motifs are imbued with an emotional charge, an indirect reaction to the impressions that reach her as an artist and a human being in the 21st century. A torn and grubby curtain, a makeshift, patched together, living hut: they depict a broken homeport, a destroyed shelter – something man has a dire need for in times of chaos. At the same time, Cloquet refers to motifs and genres from art history: the draperies in classical painting, for example, or the abstract forms of Constructivism. Broadly referencing photography, painting, (non-)architecture and sculpture, Cloquet’s works seem to transcend boundaries and, in their own way, make a bid for the notion of ‘total work of art ’. They are inclusive in the way they manage – if only for a moment – to elude extremes such as here and there, then and now, and I and the other.

Grete Simkuté

Oeuvres d'art

Articles

Médias

Points forts

Recommandations

Collections

Expositions

Position sur le marché

CV

Médias

Marie Cloquet

expositions

Dans la collection du musée:

S.M.A.K. Gent

Position sur le marché

Paris Photo - Prismes 2019 - Solo (A.Gentils) / ARCO 2019 - Solo (A.Gentils) / The Solo Project Basel 2014 (A.Gentils) / Duo show with Klaas Koosterboer Art Brussels Discovery 2018 (A.Gentils)

Duo show "Temporalizing temporality - Marie Cloquet & Peter Buggenhout", Jason Haam Gallery, Seoul, South Korea

From The Collection/Poetic Faith at SMAK, Gent 08/02 - 11/10/2020

Duo show "Temporalizing temporality - Marie Cloquet & Peter Buggenhout", Jason Haam Gallery, Seoul, South Korea

From The Collection/Poetic Faith at SMAK, Gent 08/02 - 11/10/2020

CV

Born 10/03/1976

Lives and works in Gent, Belgium

Education 1994 -1998

LUCA School of Arts – Gent

Solo exhibitions

2020

Soloshow, Halab, Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp

2019

soloshow, Paris photo prismes, Grand Palais, Annie Gentils Gallery, Paris

‘Traveling Light’ Annie Gentils gallery, Antwerp

duoshow Marie Cloquet & Guy Rombouts, Arco Madrid, Annie Gentils gallery, Madrid

2018

Duoshow ‘Temporalizing temporality’ Marie Cloquet & Peter Buggenhout, Jason Haam Gallery, Seoul

2017

‘Obstacles’ Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerpen

2016

‘ART ON PAPER’ Annie Gentils Gallery BOZAR, Brussel

2015

‘ONE’ Second room curated by Elke Andreas Boon, Gent

2014

‘The solo project’ with Annie Gentils gallery, Basel

2013

‘Nouadhibou’ Annie Gentils gallery, Antwerpen

‘YIA’ with Annie Gentils Gallery, Paris

2010

‘Picture this’ Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle

2009

‘High tide or low tide’ Argentaurum Gallery, Zoute

2002

‘photography on canvas’ Koraalberg Art Gallery, Antwerpen

Group exhibitions

2020

Coup de Ville - Chasing Flowers, WARP, Sint-Niklaas (BE)

From the collection ‘Poetic faith’ – S.M.A.K. – Gent

The Beginning of the 21st century, Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp

2019

The road is clear – In de ruimte – Gent

Group show – Jason Haam Gallery- Seoul

Art Rotterdam

2018

Biënnale van de schilderkunst – Over landschappen – Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle

‘Frame play pause’ Vierkante zaal, Sint-Niklaas

Art Brussels (with Klaas Kloosterboer)

2017

‘Vloed’ Ten Bogaerde, Koksijde

‘Yugen #art, Gent

‘Bank Gallery Projects’ Vézelay

2016

‘Intergalactic dust’ Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerpen

‘WEWANTOSEE’ Kanazawa

2015

‘Vanitas extended’ , Ieper

2014

‘Grenzen/loos’ Emergent Gallery, Veurne

2013

‘Seismology of the times’ Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerpen

2012

‘4 de Korenbeurs, Schiedam

‘Waste’ Art consultancy Tanya Rumpff, Haarlem

2011

‘Jonge vlaamse meesters’ Hermitage, Amsterdam

2010

‘Homecoming party’ Casa Argentaurum, Gent

2008

‘Event of the unforeseen’ Laugavegur 66, Reykjavik

curated by Hulda Ros Gudnadottir

‘Rewind’ vierkante zaal, Sint-Niklaas

Curated by Filip Van De Velde

2007

‘Creative space’ curated by “Chantier”, Gent

‘what’s the question’ curated by “Chantier”, Gent

2006

‘Labo#2’ vzw existentie, Gent

‘Labo#1’ vzw existentie, Gent

2003

‘Het kunstsalon van Gent’ St-Pietersabdij, Gent

(selected by: Lieve foncke, Jan hoet, Hans Martens, Edith Doove.)

2001

‘Young artists (selected by)’ Witte zaal, St-Lucas, Gent

selected by: Lex Ter Braak, Amsterdam

2000

‘Young artists (selected by)’ Witte zaal, Gent

selected by: Jan Hoet, Gent

Lives and works in Gent, Belgium

Education 1994 -1998

LUCA School of Arts – Gent

Solo exhibitions

2020

Soloshow, Halab, Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp

2019

soloshow, Paris photo prismes, Grand Palais, Annie Gentils Gallery, Paris

‘Traveling Light’ Annie Gentils gallery, Antwerp

duoshow Marie Cloquet & Guy Rombouts, Arco Madrid, Annie Gentils gallery, Madrid

2018

Duoshow ‘Temporalizing temporality’ Marie Cloquet & Peter Buggenhout, Jason Haam Gallery, Seoul

2017

‘Obstacles’ Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerpen

2016

‘ART ON PAPER’ Annie Gentils Gallery BOZAR, Brussel

2015

‘ONE’ Second room curated by Elke Andreas Boon, Gent

2014

‘The solo project’ with Annie Gentils gallery, Basel

2013

‘Nouadhibou’ Annie Gentils gallery, Antwerpen

‘YIA’ with Annie Gentils Gallery, Paris

2010

‘Picture this’ Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle

2009

‘High tide or low tide’ Argentaurum Gallery, Zoute

2002

‘photography on canvas’ Koraalberg Art Gallery, Antwerpen

Group exhibitions

2020

Coup de Ville - Chasing Flowers, WARP, Sint-Niklaas (BE)

From the collection ‘Poetic faith’ – S.M.A.K. – Gent

The Beginning of the 21st century, Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp

2019

The road is clear – In de ruimte – Gent

Group show – Jason Haam Gallery- Seoul

Art Rotterdam

2018

Biënnale van de schilderkunst – Over landschappen – Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle

‘Frame play pause’ Vierkante zaal, Sint-Niklaas

Art Brussels (with Klaas Kloosterboer)

2017

‘Vloed’ Ten Bogaerde, Koksijde

‘Yugen #art, Gent

‘Bank Gallery Projects’ Vézelay

2016

‘Intergalactic dust’ Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerpen

‘WEWANTOSEE’ Kanazawa

2015

‘Vanitas extended’ , Ieper

2014

‘Grenzen/loos’ Emergent Gallery, Veurne

2013

‘Seismology of the times’ Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerpen

2012

‘4 de Korenbeurs, Schiedam

‘Waste’ Art consultancy Tanya Rumpff, Haarlem

2011

‘Jonge vlaamse meesters’ Hermitage, Amsterdam

2010

‘Homecoming party’ Casa Argentaurum, Gent

2008

‘Event of the unforeseen’ Laugavegur 66, Reykjavik

curated by Hulda Ros Gudnadottir

‘Rewind’ vierkante zaal, Sint-Niklaas

Curated by Filip Van De Velde

2007

‘Creative space’ curated by “Chantier”, Gent

‘what’s the question’ curated by “Chantier”, Gent

2006

‘Labo#2’ vzw existentie, Gent

‘Labo#1’ vzw existentie, Gent

2003

‘Het kunstsalon van Gent’ St-Pietersabdij, Gent

(selected by: Lieve foncke, Jan hoet, Hans Martens, Edith Doove.)

2001

‘Young artists (selected by)’ Witte zaal, St-Lucas, Gent

selected by: Lex Ter Braak, Amsterdam

2000

‘Young artists (selected by)’ Witte zaal, Gent

selected by: Jan Hoet, Gent

Abonnement gratuit au magazine

Articles, interviews, spectacles et événements. Livré dans votre boîte aux lettres chaque semaine.