10 february 2026, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Jan Wattjes

Make Painting Great Again is the title of Jan Wattjes’ current exhibition at Livingstone. The title is a playful jab with a serious undertone. Painting is sometimes written off because it offers no easy certainties and does not shout for attention. For Wattjes, Make Painting Great Again is therefore about attention, doubt and sharpness.

Over the years, Wattjes has painted numerous places related to painting, such as studios and galleries. He cannot see a painting as separate from the place where it was made. For Wattjes, a studio is therefore a ‘mental state’.

Personally, he works in a home studio every other week. The thought alone of a big studio like the one his father had exhausts him. To him, a workspace must be large enough to allow free experimentation, yet remain manageable. “Painting literally takes up space and it is heavy. It’s not at all as romantic as it looks from the outside. In that temporariness, I feel freedom.”

Make Painting Great Again can be seen at Livingstone Gallery through 28 February

Where is your studio and how would you describe it?

My studio is currently at home. One week, my house is a home and the next week, it’s a studio, which is due to my co-parenting arrangement. I don’t experience this alternation as a limitation, but as something that influences my way of viewing. Because the space keeps changing, I experience my work anew each time and different perspectives emerge.

I work in silence, without music or sound. Music demands my full attention and leaves no room to paint at the same time. Working at home requires different choices than working in a separate studio. I use materials that can easily be put away again. As a result, the studio is not a fixed place, but a temporary state in which working and living converge.

In addition to working at home, I often take advantage of an artist-in-residence programme in Berlin through my gallery Livingstone Gallery called the Livingstone Project Berlin. Since 2014, I’ve worked there on a regular basis—sometimes for a few weeks, sometimes for a few months. That change of context allows me to fully focus and often generates new perspectives. The city breathes art and influences how I look and work.

At the same time, it’s a relief to experience what is considered self-evident there: a woman with a stroller in one hand and a beer in the other hardly provokes a reaction. That increasingly less prudish attitude—although it, too, is changing—gives me space and sharpens my gaze.

Wattjes Projects Berlin 2017

I sometimes dream of a large warehouse, a space where anything is possible, almost limitless, like in the film Synecdoche, New York. But at the same time, I feel overwhelmed by the thought. It also intimidates me to work when I see Anselm Kiefer cycling through his studio and doing megalomaniacal projects.

My father had a large old warehouse here in The Hague that was his studio, full of objects and materials. He built his own freedom, but he was also bound to it. Just thinking about such a space makes my head spin.

Sometimes, I dream that I end up in a maze of brick walls and dark rooms, with rats… it’s frightening and clearly relates to my father’s studio. To me, a workspace has to be large enough to experiment freely, yet still manageable. Painting literally takes up space and is heavy; it is not at all as romantic as it seems from the outside. In that temporariness, I feel freedom.

Prospects & Concepts 2017 Art Rotterdam

In your work, places and concepts directly related to painting often take centre stage. The studio itself has also been a subject. Why do you repeatedly return to these places and concepts?

In my work, I often return to places directly connected to painting because to me, painting cannot be separated from the space in which it was created. The studio is not a neutral workplace, but also a mental state. Until my second year of life, I lived in my father’s studio; a free zone where painting coincided with life—a film was shot there, there were ballet exercises and even a kickboxing match. That experience continues to shape how I work: the studio can be anywhere and a work actually already exists before it occupies a physical place. To me, that is the ‘mental studio’.

Your current exhibition at Livingstone is called Make Painting Great Again, a playful reference to the slogan of the current American president. Why does painting need to be made great again? Is there something lacking in appreciation of the medium?

The title is ironic, but also serious. Painting is constantly being questioned and that is what makes it sharp-witted. At a recent opening, I noticed how conversations often unfold: men take the floor, women listen and ask questions. I think women often adopt a position of observation and self-critique in a way similar to painting itself: tentative, reflective, sometimes alienated.

Perhaps that is why painting is sometimes written off—not because it is weak, but because it offers no easy certainties, it does not shout for attention and it is quiet. To me, Make Painting Great Again is about attention, doubt and sharpness.

Jan Wattjes, Formation, 2024, Livingstone gallery

This exhibition is also about the medium of painting. Unlike previous exhibitions, we do not see physical places such as galleries and studios, but words. In a work like Formation, we see the names of well-known painters. The names Zurier and Monet are crossed out. At the bottom, in blue, is 4-3-3, the classic formation in Dutch football. Is this your starting 11?

Formation shows a lineup of painters who interest me at that particular moment for whatever reason. It’s like a snapshot—fleeting and sketch-like—similar to jotting down an idea on a scrap of paper with the occasional edit.

Why did you replace Zurier with Malevich and Monet with Munch?

The crossed-out names, such as Monet, are not meant to suggest that I value them any less. They simply indicate where my interest lies at that moment. Ideally, I would approach every canvas like this: as a sketch, an experiment that is constantly evolving. Monet remains special to me in that he introduced me to painting, so that is where it all began for me.

The idea of the ‘starting 11’, the 4-3-3 formation, refers to the total football philosophy in Dutch football and shows what I grew up with and where I come from—it is not about pride, but about my roots, a temporary selection of references, just like my snapshot of painters in Formation.

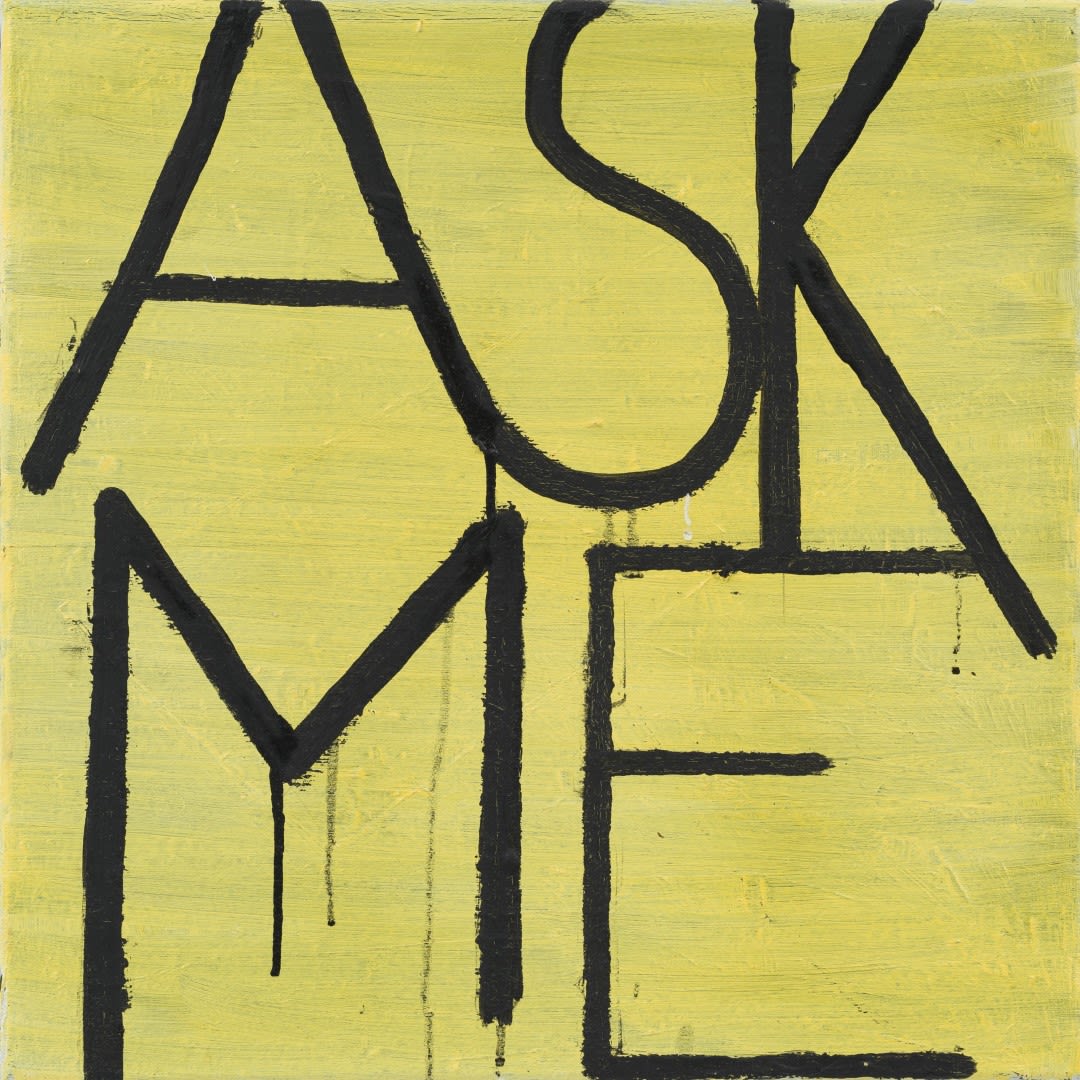

One more question about the words and short phrases such as Ask Me that appear in several works. The press release quotes you as saying: “In this series of paintings, language becomes an image. Letters, words and lines move freely across the pictorial surface—not to be read, but to be seen.” Can you explain that?

In this series, my aim is for language to become a visual element. Letters, words and lines move freely across the surface of the painting; they are not meant to be read, but to be seen and experienced.

This idea took on even more meaning for me through my son, who has multiple disabilities and communicates very little verbally or with gestures. That really showed me what language is and what it can be. Together we have developed our own way of communicating and that inspires how I work with letters and words: as forms, rhythms and lines that have their own logic and presence independent of traditional readability.

Jan Wattjes, Ask Me, 2025, Livingstone gallery

A different kind of question: when it comes to artists with a conceptual approach, I’m always curious about projects that never quite got off the ground. So, let’s dream big and suppose I have a space available and give you carte blanche—what kind of project would you want to carry out?

While working on the White Cube painting series (2015–2018), the project got completely out of hand. I made a painting measuring 360 × 600 cm, showing part of the façade of the David Zwirner Gallery (20th Street, NYC) on a 1:1 scale. I’ve always wanted to make several huge canvases like this as preparation for museum exhibitions. Those exhibitions have not yet happened, although two were planned this year. The idea is installation-like: a world of enormous, tactile paintings. If I were given carte blanche, I would love to do that project.

Jan Wattjes Atelier David Zwirner. Foto Rick Messemaker

What are you working on right now?

After the opening of an exhibition, I often experience a sense of emptiness. This has less to do with preparing for an exhibition because that’s not how I work. I do my work and at some point, there is an exhibition. The emptiness arises more from feeling exposed or observed afterwards, which takes a lot of energy. Over the years, I’ve come to recognise this pattern and try to accept it. During that phase, I often turn to a different medium. Last year, I started working with clay and while in Berlin at Livingstone Project Berlin, I explored how the sculptural can relate to painting. I worked with clay in the same way as I paint. Some of the results can be seen at Make Painting Great Again. Right now, I’m experimenting with AI, but without any specific expectations, more like playing around. Sometimes, I use something from it in a painting, sometimes not.