06 november 2025, Flor Linckens

Last chance: flesh and fiber in O-68

In gallery O-68 in Velp, the exhibition ‘On the cusp’ is on view until 16 November. The gallery brings together two related yet clearly distinct artistic approaches. While Lotte Pet examines the body beyond its familiar exterior, Mirjam Pet-Jacobs looks to the edge zones where city, landscape and social traces intersect. Together, the works reveal how both human beings and their environments are in continuous transformation.

Lotte Pet (1989) works as an artist and researcher at the intersection of painting and bioart. After studying at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, she continued her education at Leiden University, where she specialised in contemporary art and the role of biotechnology in shaping our concept of life. She completed her PhD at the same university with the dissertation ‘The Excess of Meaning. Developing an ethical attitude toward biological life through engaging with bioart’, in which she examined how art, parallel to bioscientific and bioethical discourses, can contribute to new forms of knowledge about biological matter and to a more ethical engagement with living material.

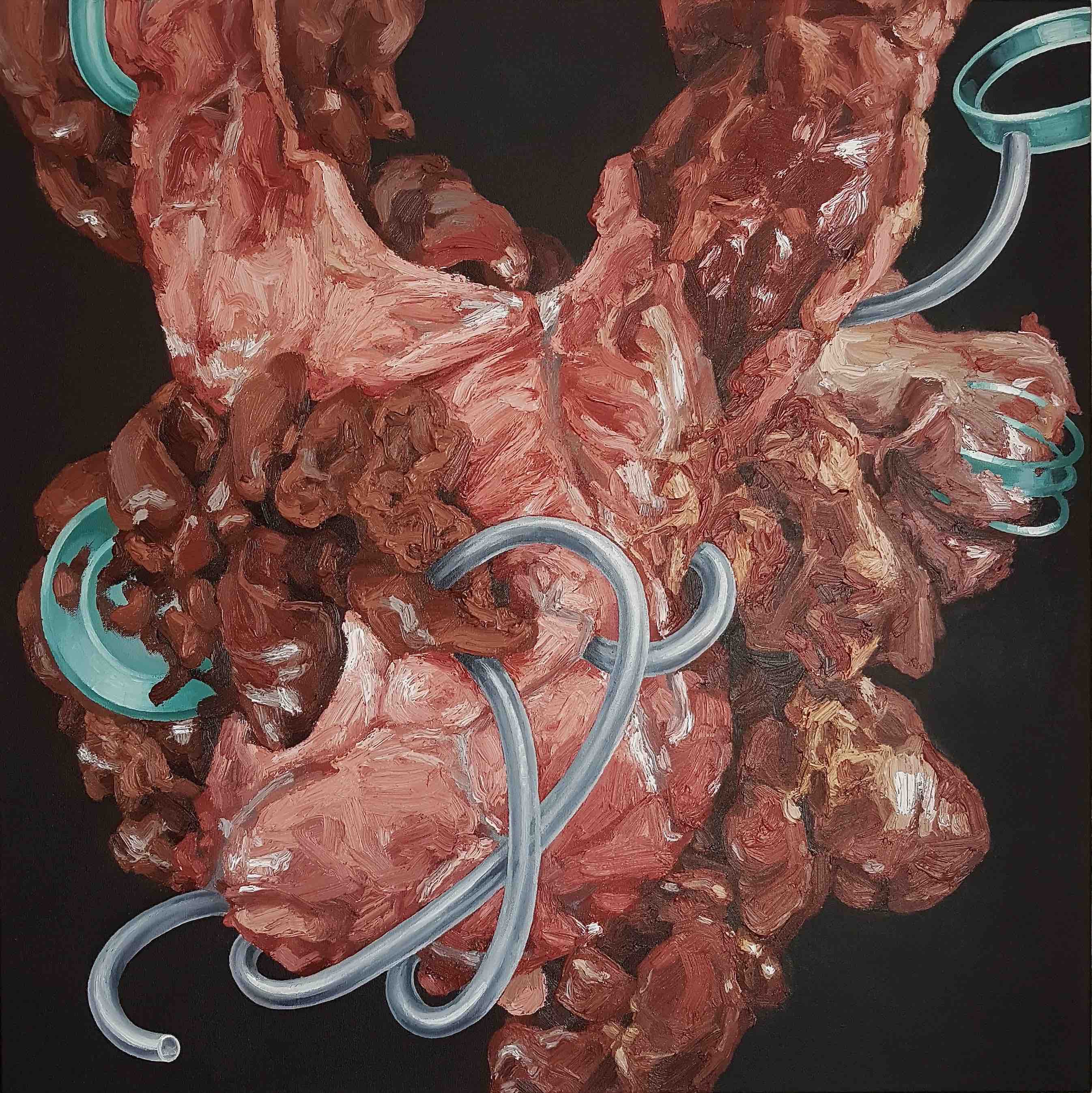

In gallery O-68, Pet presents a series of paintings in which the body is no longer self-evidently human-shaped. Many of the compositions refer to personal memories we associate with innocence: an early birthday, a day at a swimming pool, a computer classroom, a slow summer afternoon. They are painted with a slight softness, reinforcing the sense that you're looking at a memory. Yet in some of these scenes, expected figures are replaced by blob-like, fleshy structures. Where one might anticipate a third child, a compact painted form appears, referring to the interior of the body, like a growing organism. These forms are rendered more thickly than the surrounding scene, making them appear to push outward from the surface. The material seems to shape itself as one watches, as if it could shift at any moment. The scene remains recognisable, but the human figure is partly replaced by an entity that feels at once intimate and unsettling. The image becomes overshadowed by a tangible physicality that is difficult to ignore. The child appears here as a process of becoming, as a body-in-formation, taking shape as an amorphous presence. In doing so, Pet invites us not only to look at the image, but also to reconsider the assumptions we carry about development, identity and the process of becoming human, as well as the highly medicalised relationship we maintain with the inside of our own bodies.

This sense of estrangement touches on a central question in Pet’s work: what does it mean to have a body in a time when cells are grown, tissues reconstructed and organs modeled on chips? The body is no longer a closed whole, but a collection of elements that can be reused, repaired or configured. In her paintings, this is not addressed theoretically but made tangible. The works do not function as abject repulsion, but as an invitation to come closer, to examine what a body is in a time when the boundaries between biology, technology and identity are shifting.

On the Leiden University website Pet notes: “By mixing biotechnological developments with art forms, the ethical questions connected to them are approached from a different perspective. Art is often ambiguous and indistinct, and that creates a necessary confusion. In doing so, you can also look at biological life itself and what it entails. It is not singular or fixed, but rather fluid and changeable.”

In other works in the exhibition, the organic forms are surrounded by tubes, hoses and transparent plates, reminiscent of clinical turquoise laboratory equipment, making the tension between intimate physicality and controlled biotechnological environment even more palpable.

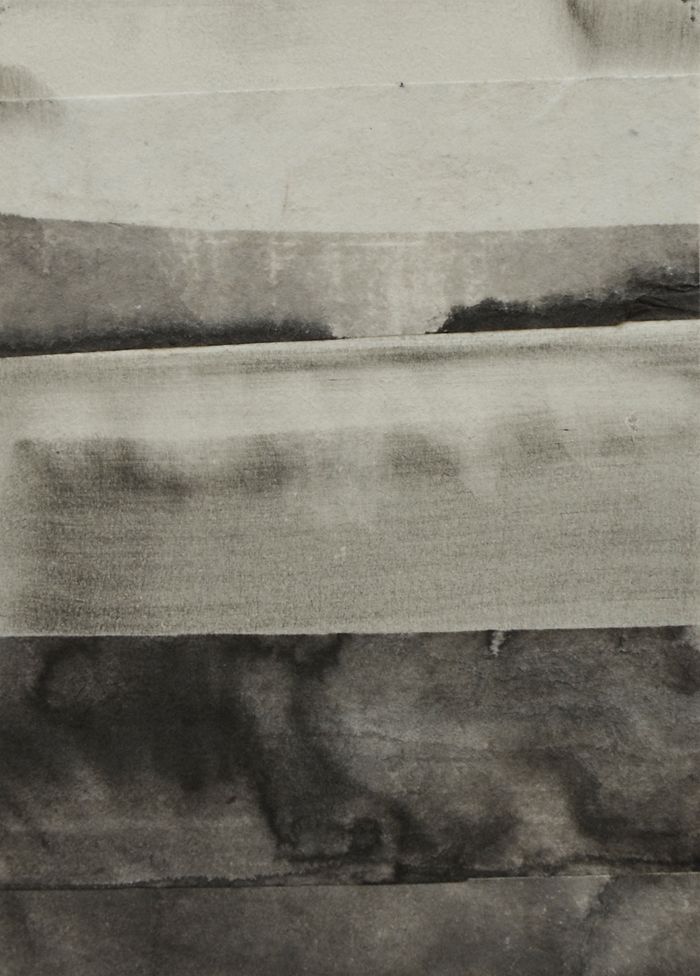

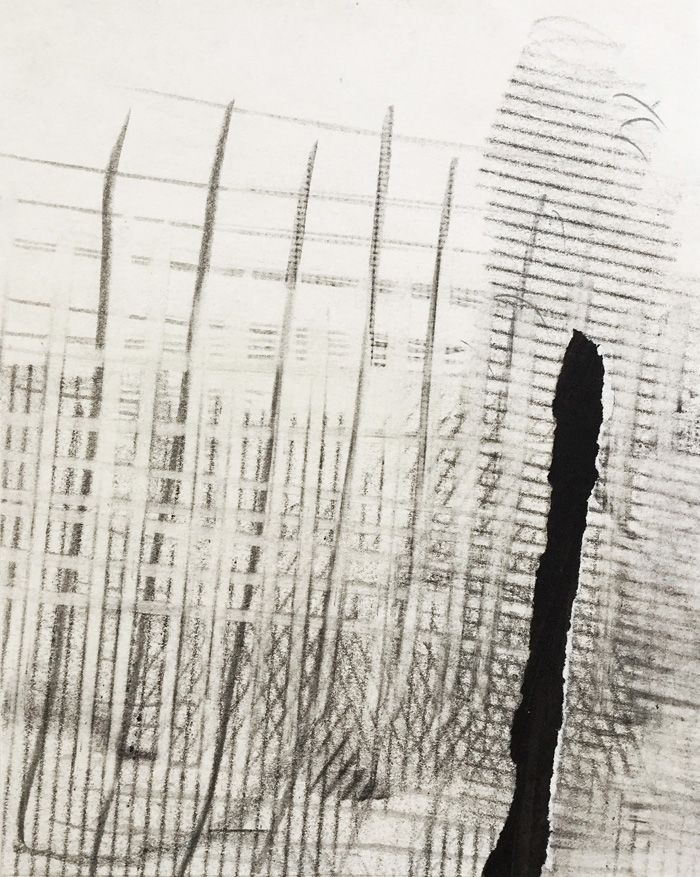

On the other hand, Mirjam Pet-Jacobs (1961) focuses on the human being as part of a social and environmental fabric. She studied English at Radboud University and later pursued drawing at Academie Arendonk. In her work, she examines border zones and transitional situations: the frayed edges where urban development and landscape meet. These edges serve as a metaphor for how societies shift over time and leave traces. Pet-Jacobs asks what we carry forward, what we leave behind and how we relate to change.

The artist works with textiles, paper and found materials, including discarded fabrics, old drawings and seemingly worthless fragments. By upcycling, she responds to the contemporary logic of quick use and replacement that shapes our society. Found material retains earlier lives, forming a quiet inventory of use, wear and memory. The bodies once connected to these materials are absent, leaving only shells and impressions. Pet-Jacobs makes visible how presence and absence intertwine in social spaces, and how traces of human presence continue even when the human itself has disappeared.

Pet-Jacobs has a multimedia practice that is shaped by paper, graphite, embroidery, paint, ink, charcoal, drawing, painting and, to a lesser extent, photography and video. She is influenced by art history and art philosophy, but also by the news and current societal problems. Her practice alternates between slowness and immediacy: embroidery requires time and attention, while drawing and printing allow for quicker, intuitive gestures. This results in two- and three-dimensional works in a restrained palette of ecru, grey and black.

Her work has been collected by Textilsammlung Max Berk, Szombathely Gallery (museum), Museum Delmenhorst and the International Quilt Study Center at the University of Nebraska. She received first prize at the Riga International Textile and Fibre Art Triennial (2015) and won the European Quilt Triennial in Heidelberg twice (2003 and 2009).

In ‘On the cusp’, the works of mother and daughter meet without converging. They share an attention to transformation but approach it from different directions: one toward the interior of the body and the matter that composes it, the other toward the edges of the landscape and the traces left there.