Connexion

S'inscrire

FR

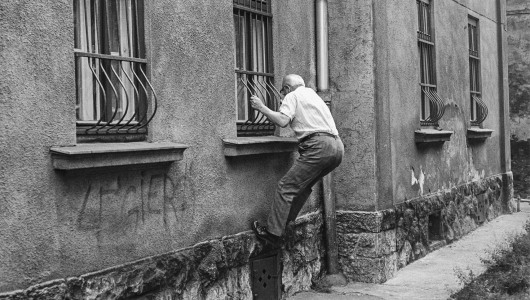

Hans van der Meer 1955

Vit à Amsterdam. Travaille dans Amsterdam.

Représenté par:

Galerie Wouter van Leeuwen

Dutch Fields

In 1995, a journalist from de Volkskrant newspaper asked me to take some photos to accompany an article about amateur football. After visiting a few matches, I knew this was a subject I wanted to pursue because it offered me the scope to develop several ideas. I initially started at the top of amateur football, but soon found myself among the lower leagues. I looked for playing fields where the background formed part of the story. On those pitches on the outskirts of villages I sought the game in its original form, as it had begun 150 years earlier in Koekamp in Haarlem, the Netherlands: a field, two goals, 22 players and little more than a horse looking on from a neighbouring pasture. In Dutch Fields, I discovered and explored the possibilities of scenic locations and experimented with different viewpoints. Sometimes the angle was elevated, as in the subsequent, more conceptual series European Fields. But just as often I stood on the ground.

I discovered space in football photos in the Spaarnestad archive in 1988. For the first time I saw overview photos taken from the stands. That was a revelation to me. In a sport where space and the positions that players occupy on the field are so essential, it is incomprehensible that sports photos in newspapers do not show any of that. For years the sports pages have been dominated by close-ups; two players against a blurred background. You have no idea where they are on the pitch. In the archives you saw radical changes taking place, somewhere around the late 1950s and early ’60s. Telephoto lenses improved and matches were broadcast on television. In the period prior to that, photographers not only sat behind the goal but also in the stands. Newspapers and sports magazines published these overview photos with a dotted line, which indicated the path the ball had travelled to the goal. This gave readers in the time before television an idea of how the goal had been scored.

Beautifully and accidentally caught in the background of these photos was a portrait of an era. Men wearing trilbies and raincoats in the stands, as well as the flags on the roof and the houses behind them. Together with former footballer and commentator Jan Mulder, I made a selection of these images from the Spaarnestad archive for the book Interland, The Dutch National Team 1911-1955 (Focus, 1988). I found the photos that showed a world outside the stadium particularly appealing.

The accidental glimpse of a street in the background with passing cars or pedestrians who are oblivious to what is going on in the stadium intrigued me. For the first time I saw the phenomenon of parallel reality. Like a theatre, a stadium stages performances. As Johan Huizinga so aptly describes in his Homo Ludens, we allow ourselves to be transported to another reality. A stadium offers the same experience as a cinema or theatre. When it is over and we return to our car in the car park, we also return to that other reality. Inside the lines our imagination has free reign, outside the lines reality takes over.

On an amateur field outside a village, the environment plays the role of sobering reality. Most amateur players realise at some point that their talent is insufficient to take them to packed stadiums. But thanks to the power of that same imagination, the amateur player does not hear the wind rustling through the poplars around the field, but the cheers rising from the stands when he scores, even though he is watched only by handful of supporters. Once inside the lines, he is transported to a different reality and becomes completely absorbed in his game.

Using a football photo as a means to fire the imagination by increasing the sense of mystery, made the subject of football immediately appealing to me. Everyone knows what they are looking at in an image of an attacker storming towards the keeper, leaving defeated defenders in his wake and a keeper standing tensely in front of his goal. Something has gone horribly wrong in the defence, but you do not see what. We also never know the outcome of the situation. In a photo, the outcome is forever unattainable.

This subject also gave me the opportunity to depict the Dutch landscape behind the football fields. In my opinion, the non-emphatic way in which things are captured in photos is precisely what increases their realism and credibility.

My most vivid memories of the period around 1995 are the pleasure and excitement of discovery, of all the things I could do with the subject of football.

In 1995, a journalist from de Volkskrant newspaper asked me to take some photos to accompany an article about amateur football. After visiting a few matches, I knew this was a subject I wanted to pursue because it offered me the scope to develop several ideas. I initially started at the top of amateur football, but soon found myself among the lower leagues. I looked for playing fields where the background formed part of the story. On those pitches on the outskirts of villages I sought the game in its original form, as it had begun 150 years earlier in Koekamp in Haarlem, the Netherlands: a field, two goals, 22 players and little more than a horse looking on from a neighbouring pasture. In Dutch Fields, I discovered and explored the possibilities of scenic locations and experimented with different viewpoints. Sometimes the angle was elevated, as in the subsequent, more conceptual series European Fields. But just as often I stood on the ground.

I discovered space in football photos in the Spaarnestad archive in 1988. For the first time I saw overview photos taken from the stands. That was a revelation to me. In a sport where space and the positions that players occupy on the field are so essential, it is incomprehensible that sports photos in newspapers do not show any of that. For years the sports pages have been dominated by close-ups; two players against a blurred background. You have no idea where they are on the pitch. In the archives you saw radical changes taking place, somewhere around the late 1950s and early ’60s. Telephoto lenses improved and matches were broadcast on television. In the period prior to that, photographers not only sat behind the goal but also in the stands. Newspapers and sports magazines published these overview photos with a dotted line, which indicated the path the ball had travelled to the goal. This gave readers in the time before television an idea of how the goal had been scored.

Beautifully and accidentally caught in the background of these photos was a portrait of an era. Men wearing trilbies and raincoats in the stands, as well as the flags on the roof and the houses behind them. Together with former footballer and commentator Jan Mulder, I made a selection of these images from the Spaarnestad archive for the book Interland, The Dutch National Team 1911-1955 (Focus, 1988). I found the photos that showed a world outside the stadium particularly appealing.

The accidental glimpse of a street in the background with passing cars or pedestrians who are oblivious to what is going on in the stadium intrigued me. For the first time I saw the phenomenon of parallel reality. Like a theatre, a stadium stages performances. As Johan Huizinga so aptly describes in his Homo Ludens, we allow ourselves to be transported to another reality. A stadium offers the same experience as a cinema or theatre. When it is over and we return to our car in the car park, we also return to that other reality. Inside the lines our imagination has free reign, outside the lines reality takes over.

On an amateur field outside a village, the environment plays the role of sobering reality. Most amateur players realise at some point that their talent is insufficient to take them to packed stadiums. But thanks to the power of that same imagination, the amateur player does not hear the wind rustling through the poplars around the field, but the cheers rising from the stands when he scores, even though he is watched only by handful of supporters. Once inside the lines, he is transported to a different reality and becomes completely absorbed in his game.

Using a football photo as a means to fire the imagination by increasing the sense of mystery, made the subject of football immediately appealing to me. Everyone knows what they are looking at in an image of an attacker storming towards the keeper, leaving defeated defenders in his wake and a keeper standing tensely in front of his goal. Something has gone horribly wrong in the defence, but you do not see what. We also never know the outcome of the situation. In a photo, the outcome is forever unattainable.

This subject also gave me the opportunity to depict the Dutch landscape behind the football fields. In my opinion, the non-emphatic way in which things are captured in photos is precisely what increases their realism and credibility.

My most vivid memories of the period around 1995 are the pleasure and excitement of discovery, of all the things I could do with the subject of football.

Oeuvres d'art

Articles

Médias

Points forts

Recommandations

Collections

Expositions

Position sur le marché

CV

expositions

Abonnement gratuit au magazine

Articles, interviews, spectacles et événements. Livré dans votre boîte aux lettres chaque semaine.