27 april 2021, Manuela Klerkx

Miguel Sbastida: We are our environment

We forget we can’t possess nature because we are nature

Last week I had the opportunity to speak with Spanish artist Miguel Sbastida (1989) about his project ‘The Possession of Touch’ consisting of a video and a series of photographs. The conversation was great fun and above all highly inspirational. Miguel studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid (2007-2012) after his BFA studies in the Netherlands (2011) and Canada (2012). Miguel is a multidisciplinary artist who explores the intersections of cultural ecology, climate breakdown and geologic phenomena. He has participated in symposiums like Climate-Truth-Now Chicago (2017), and directed the seminar Ethics for Making in the Anthropocene (2018).

Over the past few years, Miguel's work has been shown all over the world and has been very well received by museums and collectors alike. I asked him a few questions about his special approach to art and the project ‘The Possession of Touch’ in particular. The longer I listened to him the more I got impressed by the audacity with which the artist delves into complex matters such as prevailing Western theories and how these have impacted - and still impact - the way we think about ourselves and relate to the planet. Miguel believes in a future based on care and empathy from the moment we overcome the traditional distinction between the internal (me) and the external (the other/the environment). This distinction is fictional: we are our environment.

How would you describe your artistic practice?

My practice develops from very conceptual research around concerns in the field of cultural ecology, climate breakdown and geologic phenomena. I am interested in the ways in which we perceive matter and time and how it is connected across all realities. My work is highly research-driven, so I collect many influences from fields like the natural sciences, post-humanities, environmental activism, indigenous knowledge and so on. From there, I establish relationships and interrogate ideas about our ways of understanding and relating to the world and I try to explore perspectives of the human that situates us above other species of this planet.

Can you briefly describe how you proceed?

I work site-specific and use specific material to create my work which goes from installations, objects, performances and videos to writing texts. My work is interdisciplinary and I like to move across fields of study in order to learn as much as possible. I usually start my investigations out of cross-pollinating ideas. For example, perhaps I am researching the idea of the Anthropocene as a geological epoch in which human agency has modified the Earth’s cycles in irreversible ways. At that point, I am understanding the human as a geologic entity and I ask myself: in what ways are we already “geological”, not just “becoming” in merely semantic ways? Around the same time, I was reading an amazing essay about the practice of Ilana Halperin, and specifically about a detail in regards to the chemical composition of calcareous rocks and corals; as both composed of Calcium Carbonate. Then I remembered a quote from a book by Jane Bennet and remembered our bones roughly have the same composition as coral. My head connects all these different points of information across multiple disciplines and I arrive at examples that exist in our world and that question our very conceptions of the ways in which we think about it and access it. Then I develop the works from that, by paying special attention to matter as a material that has a meaning of its own. I try to let the materials reveal themselves and speak for themselves as much as possible.

Is there actually a scientist hidden in you?

There is an approach to information and a desire to really understand the mechanisms by which things operate. If I need to explain something, I need to understand it first. I guess in this way I am very influenced by science; and in fact both of my parents are researchers around food technology, nutrition and physiology. The scientific method and its contents were at our dinner table every night. I love science, in fact I almost studied environmental sciences and biology at university. I wanted to understand how things worked inside and outside of my body. I was also more of an empirical person, loving direct experience and field knowledge. Science can be too much data sometimes. We can create all possible data about a mountain or a tree; but that data is never the thing in itself. I also think Western science tries too much to be “on top of things”, but it also has its unproven theories, and it has been produced by a culture that separates the subject from the object, because science requires that space in order to be “objective and neutral”. However, it often misses unapparent interrelations among things.

Can you explain that?

A great part of my research is directed at dissolving the Western distinctions and hierarchizations between what we consider active and passive, lively and inert, biologic and geologic. These dualisms are at the core of the colonial project, and at the core of man’s separation from nature. By thinking that we are here and we are observing something t over there means that we are telling our minds that the world has gaps and separations; while in the meantime you are breathing the air that a colony of algae in front of you just produced. I believe it is important to overcome these distinctions because we inhabit the Earth as much as we are a material part of it. We are the Earth as much as we also are The Milky Way. Just a small part of it, but we aren’t separated from it. In this sense, if we are capable of overcoming the distinction between an external and an internal, it is very easy to develop an ecological mentality based on care and empathy. We care about the other because there is no other, it is also a part of us, or we will in time be a part of that.

How do you see the relationship between man and nature?

I think there is a long history of classification, hierarchization and hegemony that has been building for more than 2000 years in Western culture, which dominates the ways in which we relate to the world around us. If we think about the pyramid of natural beings, or the hierarchies of matter, that distinction not only exists in our thinking but in the material world we create. The same rules of domination we apply to exploit nature were - and still are - used in colonial forms of domination; they are part of the same ideology. Guided by cultural or religious heritage, we often come to accept certain ideas that tell our brains that nature is always there at the service of mankind. We forget we can’t possess nature because we are nature. What we have is the choice and the responsibility of understanding the choices we make.

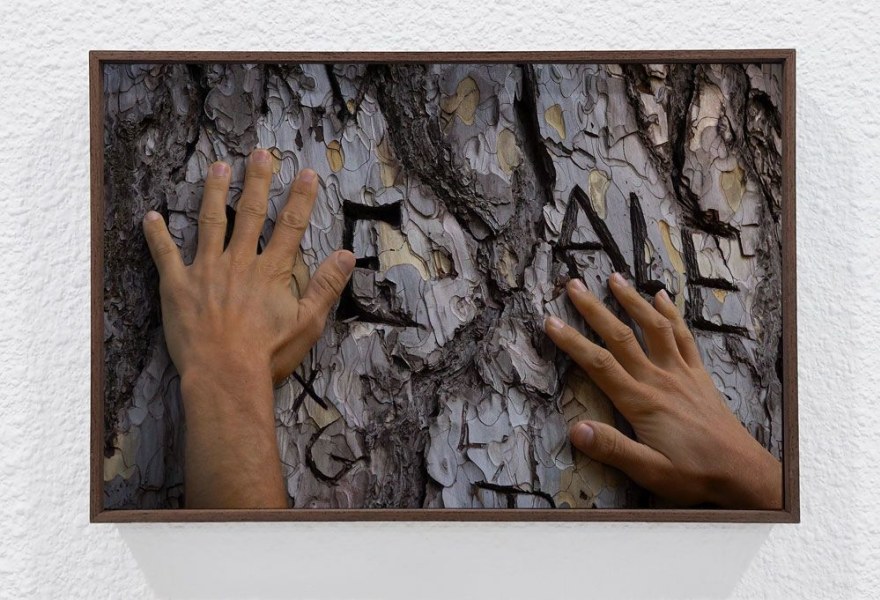

Can you explain this vision against the background of the edition “The Possession of Touch”?

Just at the end of 2020, I carried out a performance (without an audience) called “The Possession of Touch”, that I documented through a video artwork. In the performance, I use my hands and body to caress the surface of a centennial tree that was completely covered by the initials and names of people who visited it over time. These marks had been carved deeply into the bark of the tree, with the use of a knife. I was touched by the aggression perpetuated to a creature who has known its own identity well before anyone ever inscribed their name on it. My reaction was to caress the surface of this tree until the fragments of bark that carried the initials were gone from the tree. I saw the act in itself as an act of empathy and care towards a non-human, but also as the contrast between my unmarked skin and that one of the tree. Both carrying its personal histories; the imprint of time. Also, taking into consideration that the skin is a surface that has been historically used as a reason to discriminate, kill, possess, hierarchize and control. In a way, liberating the tree from these incisions entailed liberating it from those histories of appropriation and colonial mindsets, and to restore that relationship through care and nourishment. Out of this performance I produced a selection of photographs documenting the entire process. Beyond the pictures, the performance has also been documented through a video that is stored in a wooden box made from the very bark fragments of the tree.