06 april 2021, Wouter van den Eijkel

Sanlé Sory: Jour & Nuit

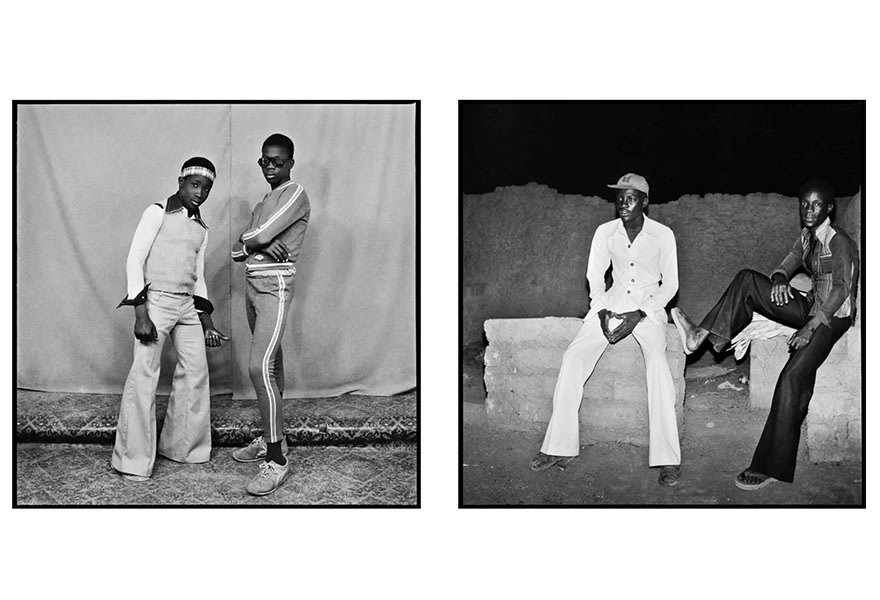

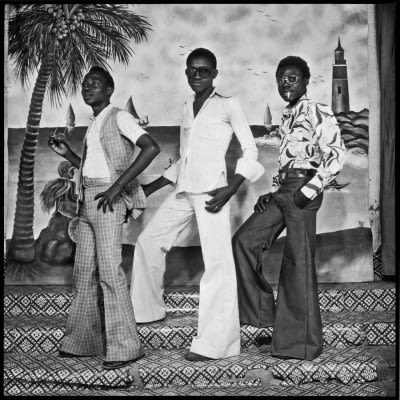

“I have seen people enter my gallery looking somewhat depressed that left smiling", says gallerist Wouter van Leeuwen about Jour & Nuit, his second exhibition with work by the Burkinese photographer Sanlé Sory. That shouldn't come as a surprise, as the youngsters populating Sory's photos are brimming with energy, pride and dreams for the future. They remind us of what is temporarily impossible: living carefree and making plans.

Souvenirphoto’s

Like his Malian colleagues Malick Sibidé and Seidu Keïta, Sory (born 1943) took so-called souvenir photos. Often labelled Africa’s greatest contribution to 20th century photography, souvernir photos are not traditional portraits, but portraits that were taken with friends, with bands, at parties or after a night out. A memory of a moment. According to Sory, the physical photo was not the most important thing for those portrayed, but the fact that they had their photo taken.

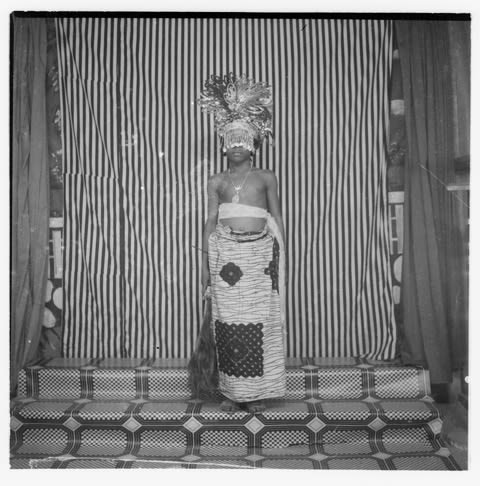

Sory established his studio Volta Photo in the city of Bobo-Dioulasso in 1960 and worked against the backdrop of Upper Volta’s recent independence from France. His photos show a country in transition. Some wear traditional clothing, others embrace the counter culture of the 1960s. In Sory’s studio they dressed up in costumes and props that Sory had created and collected.

MC and photographer

Sory not only had his photo studio, but from 1970 also organized parties for 25 years in villages surrounding Bobo. At these parties he was not only the MC, but also the photographer. To the visitors the presence of a photographer meant that it was a good party. The goal was to be photographed, the photo itself was the by-product.

As a result, Sory knew many of the portrayed personally and was able to tell the story behind most of the photos years later, as with 1975’s Les Chaussures des Riches (The shoes of the rich):

“These young Fula pretended to smoke like famous people. They just came out of the slaughterhouse and spent the money they just made. They wore plastic shoes, also called "shoes of the rich," which are very practical for field work or for wading through shallow water.”

“This guy had a very nice Yamaha motorcycle and wanted to be photographed with it. We had to go into the studio with the motorbike. […] This was a night session because I worked with spotlights. For our nightly customers, we were sometimes open up to 2 a.m.

Too good to be true

Sory owes his current fame not to his photo studio nor to the parties he organised. The fame has to do with his work for the record label Volta Jazz to which his cousin was connected. The story is too good to be true. The French music connoisseur and historian Florent Mazzoleni was working on a book about Burkinese music. He was looking for Sory to discuss the cover photos he took for Volta Jazz. It turned out that Mazzoleni arrived just in time, as Sory was just starting a fire to burn the photographic negatives of every portrait he ever took.

After their first encounter things went fast. Photography is the medium in which a complete oeuvre is occasionally found and added to the canon. The best-known recent example of this is Vivian Maier. The American has worked as a nanny all her life, a kind of Mary Poppins who spent her spare photographing street life. Her inventory was bought at a foreclosure auction after her death. Shortly afterwards, the quality of Maier's work was recognized, shown all over the world and compared to that of the greats of street photography such as Freedlander and Winogrand. Something similar is happening now with Sory's work. Nowadays, his name is bracketed together with Sibidé and Keita.