06 january 2026, Yves Joris

Wim Nival: it starts in the small

It is in the smallest works that I have the opportunity to find a path toward experiencing the greater whole. This sentence greets you as a visitor to the website of Wim Nival. No statement in capital letters, no explanation, no context. Just that single thought, soberly phrased, almost in passing. In hindsight, that sentence alone is food for thought. But it was only when I first encountered his work physically that it began to take on more meaning.

That first meeting took place at Settantotto. Small works of art, modest interventions, materials that carry their story without displaying it. Nothing imposing. Everything asking for time and the enthusiastic explanation of the gallery owner.

The quotation on his website began to serve as a key. Not as an explanation of the work, but as an attitude that could be felt throughout the oeuvre. The small elements as a passage, as a way of not naming the greater whole, but approaching it, tot through the spectacular, but through attention, repetition, silence.

That experience—the convergence of that one sentence and concrete encounter with the work at Settantotto—was enough for me to want to engage in dialogue. Not to have the work explained, but to understand how such a practice comes into being. What precedes that sobriety. Where that slowness comes from. How a life slowly translates itself into forms, holes, lines and rhythms.

The conversation in Wim Nival’s studio unfolded as his work grows: without a fixed plan, with detours, with silences that did not need to be filled. What follows is not an interpretation of an oeuvre, but a dialogue about youth and formation, about collecting and letting go, about time, walking and wonder. About art not as a result, but as a way of living.

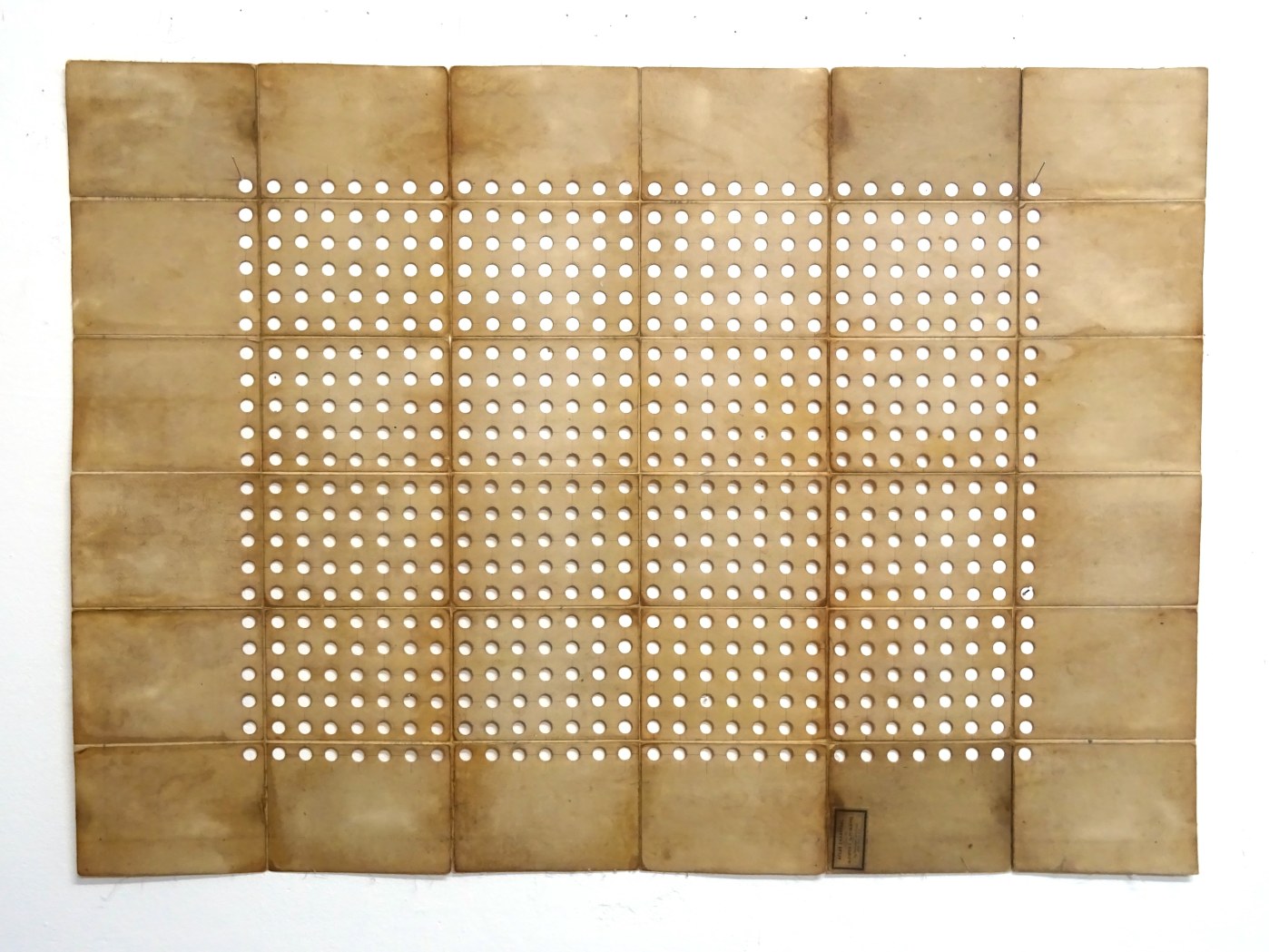

Wim Nival, Z.T., 2023, Settantotto Art Gallery

You have been active as an artist for 35 years now. For those who do not yet know your work, how would you summarise those years?

For me, art has essentially always been a way of life. The work that results from it are traces of that way of life. I don’t think in a result-oriented way. It’s about a process of being engaged, of looking, of acting, and things emerge from there. That has always been the case.

Has that drive always been there?

Yes. As long as I can remember, I wanted to become an artist. As a child, I was always drawing, painting, making things. That was not a phase. That was simply who I was. But I belong to a generation in which you couldn’t just go straight into art education. I actually wanted to go directly to Sint-Lucas, but that wasn’t possible at the time. So, I first had to earn a classical diploma.

You followed a scientific track.

Exactly. I studied mathematics and sciences at a college next to Sint-Lucas. In retrospect, that wasn’t lost time. From my classroom, I could look out onto the sculpture garden at Sint-Lucas. Every lesson, I was literally looking at it. I knew that’s where I needed to be. When I was 18 and allowed to choose freely, I immediately went to Sint-Lucas, now called LUCA. It felt like coming home.

You started with painting.

Yes, painting was my training. Object art was not often addressed at the time. But I quickly evolved toward a more minimal approach. At a certain point, I began painting on old sheets of paper and then I realised, the material I paint on already carries meaning in itself. That was a turning point. From there, I began working with paper, books, cardboard and later also with wood, iron, found objects.

Wim Nival, Z.T., 2023, Settantotto Art Gallery

Your studio is full of materials. What are your thoughts on collecting?

I collect a lot. I go to thrift shops, flea markets, second-hand shops every week. But it’s not collecting in order to possess. They are things that appeal to me, that carry something within them. Sometimes, I know immediately what I want to do with them, sometimes they lie around for years.

How do you know when something becomes ‘the right’ material?

That happens intuitively. I often work with trial and error. I lay things on the floor, make combinations, look at them for days or weeks. Nothing is glued or fixed right away. Only when I feel that the image is right does that happen. And sometimes it doesn’t happen at all.

That requires a great deal of patience.

Yes, but it’s not patience in the sense of waiting. It’s more about allowing. Some potential works lie here for a year held together with elastic bands. Thijs (Dely – gallery owner of Settantotto) once came by, saw such a sculpture lying there and said: I’d like to show that. But for me it wasn’t finished yet. If I don’t feel that the moment is right, it doesn’t happen. Not even for an exhibition.

Your work is often described as minimalist. Do you agree?

I can live with that term. For me, it’s about seeing the small, the quiet, that which is passed by. I always try to find a balance between the materials I find and the interventions I make. Those interventions are minimal, but I hope the work is never experienced as cold or distant. On the one hand, there is the material itself and on the other, the action and reflection that keep the human scale within it.

Wim Nival, Z.T., 2025, Settantotto Art Gallery

That fragility is important. It doesn’t have to be loud. I don’t believe that art always has to shout for attention. Sometimes a whisper suffices.

How important is the space in which your work is shown?

Very important. The ideal place is actually the studio, but once the work goes outside, the space becomes decisive. I never bring a fixed plan. I start with one work and build from there. It has happened that in the end, I remove the first work again because the whole has taken another direction in the meantime.

Does a dialogue then arise between the works?

Yes, inevitably. Each work can stand on its own, but as soon as you place things next to each other, a relationship arises. I then look at colour, line, rhythm, content. What happens between these works?

Wim Nival, Z.T., 2018, Settantotto Art Gallery

In your work with books and perforations, absence plays a major role.

That’s right. Sometimes I consciously choose a book because of its title. I then borrow that from the author as it were. Like the book Pensées by Blaise Pascal. Through perforation, the object becomes both present and absent. You look through it. What, then, is still the work? What is there and what has disappeared? I find that contradiction fascinating.

That also touches on the philosophical.

Certainly. I am very interested in the being of things. What does it mean that something exists? A table seems solid, but is actually a vibration of molecules. What exactly is presence? And what is absence? That field of tension interests me enormously.

What if the viewer’s interpretation does not align with your intention?

I don’t see that as a problem. On the contrary, people can be moved by something I did not consciously put into it. I often compare it to an icon: the object itself has no value, but through the dialogue between looking and being looked at, it gains meaning. I do not want to impose what someone should see.

Your working process is very slow and repetitive.

That slowness is essential. With perforating, for example, you go hole by hole. After a while, you enter into a rhythm. Then you no longer think consciously. Everything falls away except you, the material and the action.

Does the hand still think then?

At first, yes. You literally have to know how many times to strike, how the material reacts. But after that the rhythm takes over. One, two, three. Then it becomes almost automatic. That is a state I find very important.

Wim Nival, Z.T., 2025, Settantotto Art Gallery

Time seems to be a recurring theme in your work.

Time occupies me greatly. I once made a work—an intervention in public space—with only the words ‘yesterday’ and ‘tomorrow’. For me, that was about not lingering in the past and not being too much in the future, but about what you are doing now. About presence.

I also notice that during this interview you’ve spoken a lot about walking.

I walk every day, often along the same route. And yet I see something different every day. For me, that is also an exercise in attention. Wonder is essential to me. If that disappears, everything stops.

Finally, when you look back on 35 years of being an artist, what remains?

Wonder. Attention to the small. The realisation that what we do is important, yet also relative. We are only a tiny part of a larger whole. And perhaps that is precisely what is liberating.