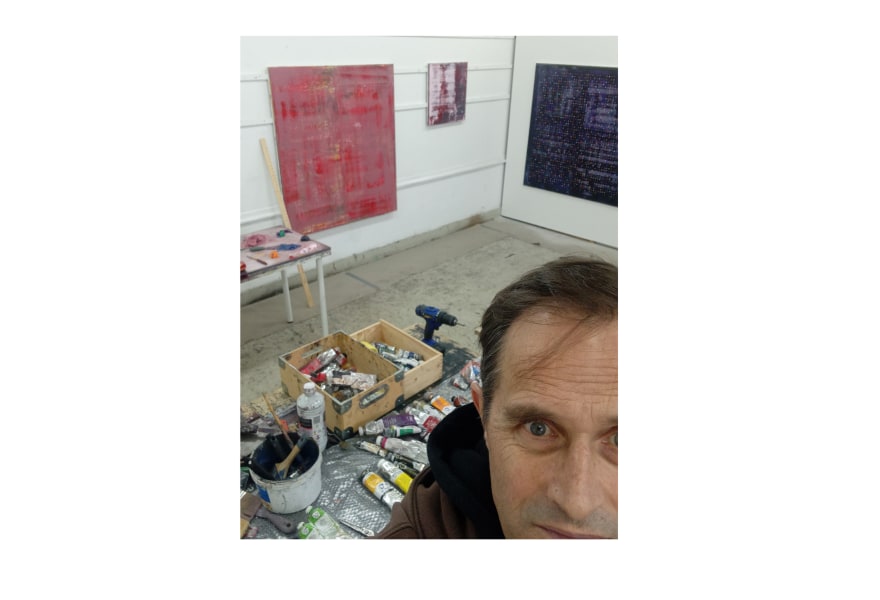

23 december 2025, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Ronald Zuurmond

Apply thickly and then scrape off. Repeat and then repeat again. Ronald Zuurmond made his name before the turn of the millennium with this method, born out of necessity. He applies the paint partly by hand and using wooden slats—and you can tell. Since then, he has steadily created an oeuvre of still lifes, more abstract work and figurative paintings.

Although Zuurmond’s working method may be fairly unique, he still feels a strong connection to his illustrious predecessors. Twenty years ago, he stood a metre away from a self-portrait by Rembrandt, closely observing the choices the artist had made. “That was when I experienced time falling away. I could look at choices made hundreds of years ago, at the consequences of those choices. And by studying those choices, I communicate with the maker.” Zuurmond speaks of a deeper time, a time that exceeds the measure of a human life.

Here and Now, the solo exhibition currently on view at Roof-A, presents an overview of the works Zuurmond has made in recent years. Personally, he did not immediately see how such an overview would look, but allowed himself to be convinced by gallery owner Lobke Broos. “She sees possibilities I didn’t see and invites me to look at my work differently.”

Here and Now by Ronald Zuurmond can now be seen at gallery Roof-A in Rotterdam.

You have a studio in Breda. How would you describe it?

It’s an attic space with daylight coming in through two north-facing dormer windows. That’s why, when I work, the fluorescent lamps are always on. The space is about 60 m². There are two walls where I hang work that I’m working on and to look at: one wall of 8 metres and one of 5 metres. I use part of the space for storage. There’s also a table to work at and another table with painting materials, as well as a lounge chair I use for reading and relaxing.

What is essential for you when it comes to a studio?

In recent years, I’ve been able to experience what it’s like to have living and working spaces close to each other. And it suits me well. The possibility to step in and out of the work at any moment, 24 hours a day, fits my nature. I’m used to being alone and I like being in a wooded environment where you don’t constantly experience human control over the surroundings. So, to me, a good studio is connected to a home, preferably with nature around it.

Is it a place where you receive visitors or do you prefer to keep the door closed? In other words, is it a special place for you or more of a functional space?

To me, the studio is currently a workplace—and therefore purely functional. I don’t particularly like being there. I make the best of it and do so through working. When I’m working, I forget everything around me. Occasionally, I receive colleagues and friendly collectors, a small group of people I know well and with whom I like to discuss my work.

In early interviews with you, from before the turn of the millennium, you said you approached being an artist as a 9-to-5 job. Waiting for inspiration makes no sense because it only comes a few times a year, you explained. What does a typical day in the studio look like?

I like to go to the studio early, not at fixed times like before, but when I feel like going. Somewhere between 6 and 9 in the morning is a good time to head to the studio. I then see what the day brings. Sometimes I take a break, listen to music or a podcast, read a bit and paint. Sometimes, a painting grabs me and I become absorbed in the work; then time just flies by.

I like feeling like I can hang around a bit in my studio. I also like working at the end of the day, when dusk sets in. I always enjoy when day turns into evening, the light becomes muted and the sounds outside suddenly change.

Ronald Zuurmond, Vazen, 2025, ROOF-A Gallery

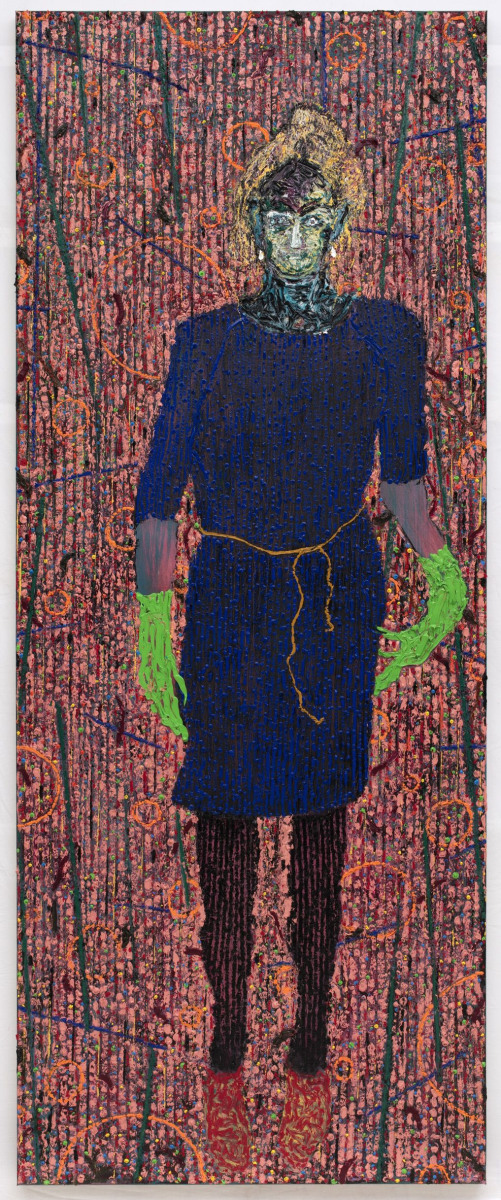

You’re known for your paintings with countless layers of paint. You apply the paint thickly and then sand away what doesn’t work, making the works a physical experience for the viewer. How did this way of working come about?

My method actually arose from a lack of money and materials. As a result, I kept reusing canvas and paint. By repeatedly scraping off and adding again, I ended up with large lumps of paint. That paint became ‘contaminated’ with crusts and turned tough and viscous, and the colours dulled. You can no longer work that paint with a brush. That’s why I started using slats to apply it to the canvas. That’s how I discovered that I could work well in layers of paint in which I sort of see the possibility of an image. I continue working from there. I also discovered that I prefer having my hands in the paint rather than hold a brush.

Congratulations on Here and Now, the exhibition at Roof-A! The accompanying text says that the work is both timeless and current and interconnected with deep time, a time measured in units larger than a human life. Do you remember when you first became interested in that subject and why?

Almost 20 years ago, I was standing in The Hague about a metre away from a self-portrait by Rembrandt. While I was trying to see how it was made, I became aware of the fact that Rembrandt had stood at the same distance from the painting to work on it, to look at it, to make choices, to apply paint, to remove it. And I experienced time falling away. I could look at choices made hundreds of years ago and at the consequences of those choices. And by studying those choices, I could communicate with the maker.

Have you had that kind of experience more often?

A few years ago in Conques, I had a similar experience in the 12th-century abbey church. On the outside is a magnificent tympanum of the Last Judgment. On the inside you stand in the old time, but the windows are by Pierre Soulages. Old and new are connected by human hands that leave traces in time—people like us. By standing there and imagining all the people who have entered that place over time, all the words that have been spoken there, how history has been written, small and large, I feel connection. Time is no longer a 24-hour clock resulting from industrial compulsion, but a deeply felt experience of connection.

Ronald Zuurmond, Love of My Life Waiting, 2025, ROOF-A Gallery

If you let the titles of the individual works sink in, them seem fairly independent of each other: Vases, No Party, Love of My Life Waiting. Is the ‘here and now’ of the title then the overarching concept? No past and no future, only the present.

Absolutely. I make a still life in response to the things around me. But if I see someone wearing an orange shirt and blue trousers and those colours trigger me, that might be the reason to make a painting in two colour combinations. Everything around me can be a reason to create an image. The connecting factor is the way I paint and the way I organise the image.

Before this interview, you said that you’re happy with the exhibition and how it’s installed. Can you elaborate?

When Lobke Broos came to the studio to select works for the exhibition, she suggested showing a broad picture of the past few years: still lifes, more abstract works and figurative paintings.

I couldn’t immediately picture such a presentation, but her enthusiasm was contagious. The best part is that she sees possibilities I didn’t and in doing, so she invites me to look at my work differently. Only during the installation, in which Lobke had already placed a few accents, did I immediately see that the works go together well.

A colourful abstract piece with dots can work well next to a dark painting with two children, and next to that a colourful still life, with a larger abstracted image of a wall hanging on the adjacent wall. So, I’m very satisfied with the exhibition and also with the way it came about, from the selection of the work to the installation.

Suppose I were to give you carte blanche and time and money were no object—would there be a project you’d like to carry out?

A wonderful question. Carte blanche and time and money don’t matter! Then the project would simply be to continue, to live and work, but in a place about 1,000 kilometres further away where I feel particularly good. You would get all the work I make and you’d be free to do whatever you want with it. I could go on there until I kick the bucket. Deal.

Ronald Zuurmond, Dots (middernacht), 2025, ROOF-A Gallery