25 march 2025, Flor Linckens

Art Rotterdam: 5 x rewilding the white cube

Rewilding is the act of restoring ecosystems by letting nature take its course: not through intervention, but through release. No rigid lines, no human control, but space for spontaneous growth, decay and surprise. While rewilding usually refers to forests, rivers or grasslands, some artists are applying the same principle. Increasingly, they are choosing to break open the tightly controlled environment of the white cube, that iconic and clinically white exhibition space, seeking ways to reintroduce the wild, the organic and the unpredictable into the context of art. Rewilding the white cube, then, goes beyond simply incorporating natural materials: it invites us to rethink our relationship with nature, to surrender control and make space for decay, growth, symbiosis and sensory experience.

At Art Rotterdam (28-30 March at Rotterdam Ahoy), several artists present works that embody this reintroduction of the wild. Their approaches range from the literal inclusion of fungi, seeds and shells to digital reconstructions of cultivated jungles and critical reflections on colonial classifications of nature. What they share is a desire to blur the boundaries between culture and nature, allowing the white cube to take root once more in the world beyond its walls. In this article, we highlight five artists who are bringing a touch of wilderness back into the art world.

Stefano Caimi will presents his “Polypore” series in the booth of The Flat – Massimo Carasi. It’s a body of sculptural works that is inspired by the way mushrooms bloom on tree trunks. "When I am in the forest, I am always impressed by the mushroom blooms on tree trunks," he says. For this series, Caimi uses real lignicolous fungi, which are first coated in a graphite-based conductive paint. They then undergo copper electrodeposition, resulting in delicate, shimmering objects where organic matter is preserved beneath a thin metallic skin. "Having always used computational systems as tools for aesthetic investigation," he notes, "I am fascinated by the idea of being able to change the material of an item." In these works, the mushroom becomes both subject and vessel — a symbol of transformation and the natural cycles of decay and renewal. Caimi subtly underscores the crucial role fungi play in ecosystems, as unseen agents of balance and regeneration.

Imagination and humour play a key role in the work of Bram de Jonghe, on view at the booth of DMW Gallery. In this piece, he combines HEPA filters with seashells, creating an unexpected and poetic encounter between technology and nature. A HEPA filter (High Efficiency Particulate Air) is designed to remove microscopic particles such as dust, pollen and bacteria from the air. Commonly found in vacuum cleaners, aircraft and medical equipment, it symbolises the human desire to exert control over our environment. By weaving this functional technology together with fragile, organic shells, De Jonghe playfully subverts the idea of control. The result is a hybrid object that teeters between the artificial and the natural, the useless and the meaningful, subtly poking fun at our urge to categorise and impose order.

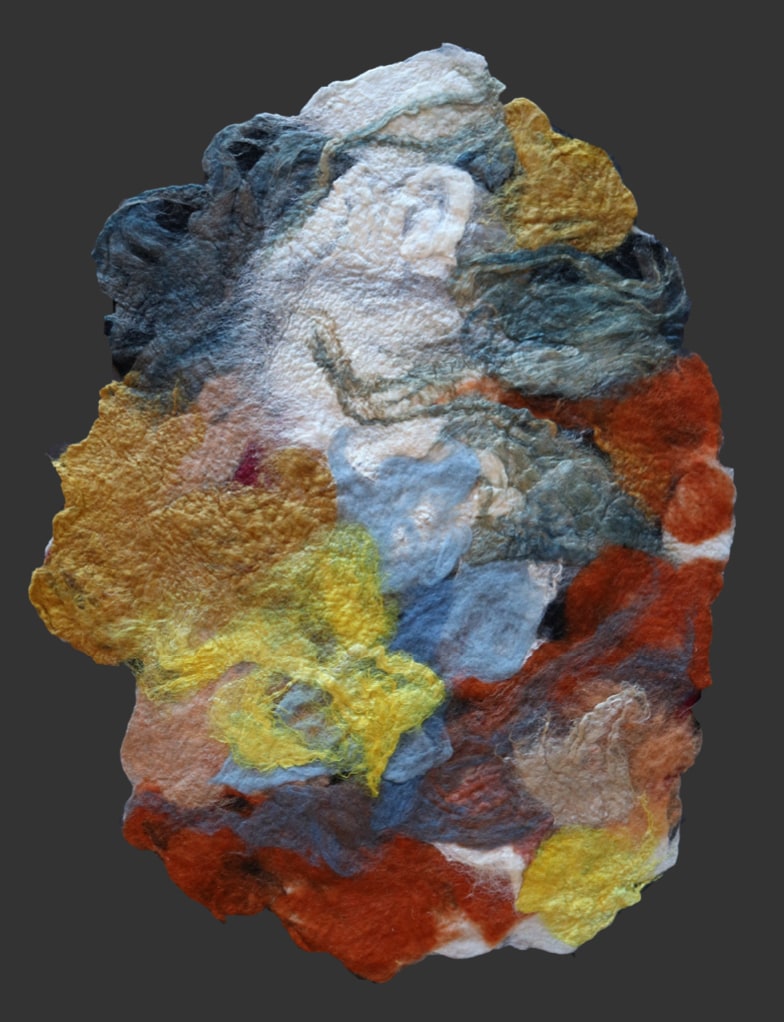

The works of Claudy Jongstra are instantly recognisable through her distinctive use of wool and natural pigments. The artist creates poetic, layered and sculptural wall pieces and installations that invite us to reflect on the intricate interplay between humans and nature. To do so, she transforms wool into felt, one of the oldest forms of textile. This is no arbitrary choice: felt is known for its protective qualities, rendering it into a powerful metaphor. It is also a remarkable material with a unique set of properties that cannot be replicated chemically or synthetically. Jongstra’s practice is grounded in in-depth material and colour research, as well as historical investigations into dyeing and craft techniques from the 15th and 16th centuries. She also employs innovative contemporary methods, always with a deep respect for humanity, cultural history and inherited knowledge, and above all: for nature. Jongstra’s artistic practice is a continuous inquiry into the relationship between art, ecology, sustainability and activism. Her holistic approach to materials is reflected in her largely circular production chain, which includes her own herd of more than one hundred rare Drenthe heath sheep, the oldest breed in Northern Europe. She uses pigments derived from plants grown in her specialised biodynamic garden, thereby protecting certain species and helping to counter biodiversity loss in the surrounding landscape. The self-sufficient working method of her studio goes beyond an ecological statement: it is a call to revalue craft and biodiversity, principles increasingly under threat in a society driven by efficiency and overconsumption.

Margit Lukács & Persijn Broersen, an artist duo that has been working together since 2001, are presenting the work "I Wan'na Be Like You" in the Projections section at Art Rotterdam. In doing so, they offer an intriguing interpretation of rewilding through a digital process. The duo’s work explores various tensions. They examine the ways in which fiction dictates reality and vice versa, as well as the relationship between people and their immediate environment: nature and society. How is this relationship influenced by the vast amount of media we consume daily, both consciously and unconsciously? Their work aims to show how reality, fiction, and (mass) media are intrinsically intertwined. They emphasise this by combining filmed or photographed footage with digital animation and media images. Their works often create parallel worlds, reflecting our society and visual culture. They are particularly interested in how people experience and construct nature. The work "I Wan’na Be Like You” critically examines the Western perception of the jungle as ‘undiscovered’ and ‘pure,’ symbolising colonial desire. The film was created through a complex process of photogrammetry, 3D molding, motion capture and CGI, resulting in a virtual representation of this ‘conquered wilderness’ based on thousands of photos that the artists took in numerous famous European botanical gardens, including Kew Gardens in London and Jardin des Plantes in Paris. The nameplates of the plants are also included to emphasise the artificiality. This ‘wilderness’ is thus primarily the ‘conquered’ wilderness as it was selected, categorised, and conserved by the West.

In the film, this digital reconstruction of nature serves as the backdrop for a dancing avatar, a mysterious ghostly figure that is not entirely human, performing a choreography by Andreas Hannes. The avatar moves to a new version of 'I Wan’na Be Like You (The Monkey Song)’ from Disney’s Jungle Book (1967), reinterpreted by David Lukács as an homage to the New Orleans jazz tradition that Disney borrowed from. Additionally, Jamal Bijnoe and Orlando Ceder of the Black Harmony choir rearranged the melody into the song 'Na Mi’ (‘I Am’ in Sranan, a language spoken in Suriname), a powerful indictment of the racist and colonial undertones of the original while celebrating their ancestral history. The work reflects on the exploitation and categorisation of nature (and human beings) by colonial powers and its implications in our current times.

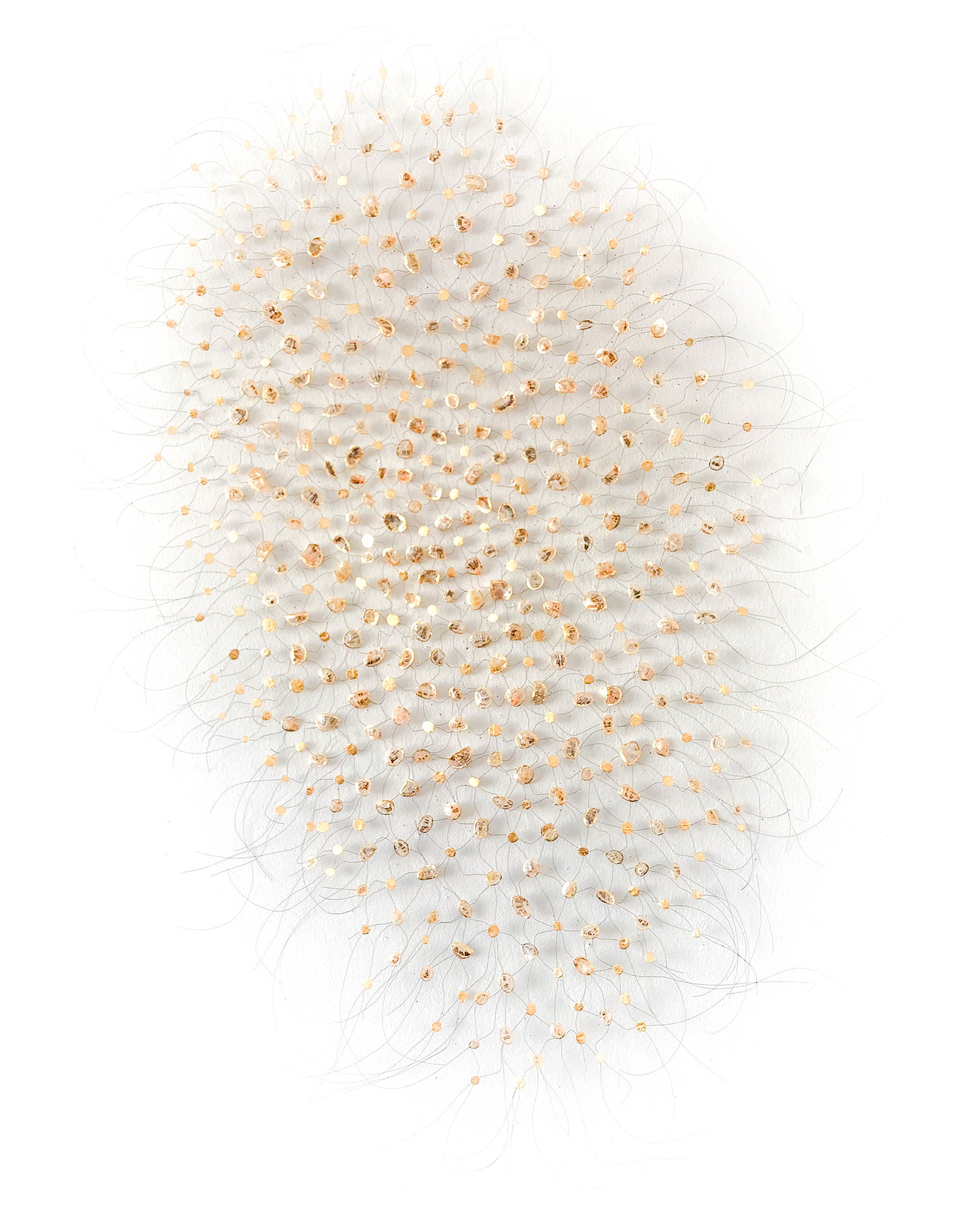

Transience plays a central role in the practice of Gerda Maas, whose work will be on view at the booth of Janknegt Gallery. She collects seeds that have fallen from trees, as well as other fragile materials such as wool, rice paper and other found natural elements. Each delicate fragment is carefully encased in polymer, a mixture of resin and synthetic material, then bordered with 23-carat gold leaf, as if to ritually elevate the everyday. The individual components are connected with pins or fine metal wire, forming a subtle trace of movement across the wall, a visual echo of drifting and dispersal. Maas shows how even the most delicate can claim a place — not by dominating but rather by quietly whispering.

View the full catalog for Art Rotterdam here and get your tickets for Art Rotterdam here.