03 december 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Bert de Geyter

Bert De Geyter goes on a walk through a nature reserve near his studio in Ghent every day. To him, these walks are a form of meditation, an endless exercise in observing, seeing and understanding, as well as a source of new ideas. For his series Mnemosyne, a collection with a nature focus, he worked intuitively, but always based on observation. “I consider it a form of respect for the things around me. By repeatedly observing, you gradually learn to see, get to know and understand the place where you live. This requires care, which nature effortlessly compels.”

According to De Geyter, his work reflects an undercurrent—a space for universal, timeless, existential matters like life and death. He interprets these in a way that does not align with the customary Western view in which death is often seen as part of life. To him, it is the exact opposite: “Life is part of death, the vast source of energy from which all life arises and to which it ultimately returns. Death is the gravity.” De Geyter seeks to confront the obvious, saying, “I simply cannot avoid speaking about the things that lead us away from or mask the essence.”

The exhibition Fieldworks, featuring work by herman de vries, Bert De Geyter and Marlise Breye, can be seen at the Settantotto gallery in Ghent until 2 February 2025. De Geyter’s work will also be featured at Art Antwerp (12–15 December) at the Settantotto stand.

You live and work in Ghent. How would you describe your studio?

My studio is at home, located just outside the city at the very back of a small urban garden. It’s a wooden structure with a large window facing the garden and three skylights that flood the space with natural light. A small stove keeps it warm during winter. Everything left uncovered eventually turns black, so it’s not a somewhere you want to wear light clothing.

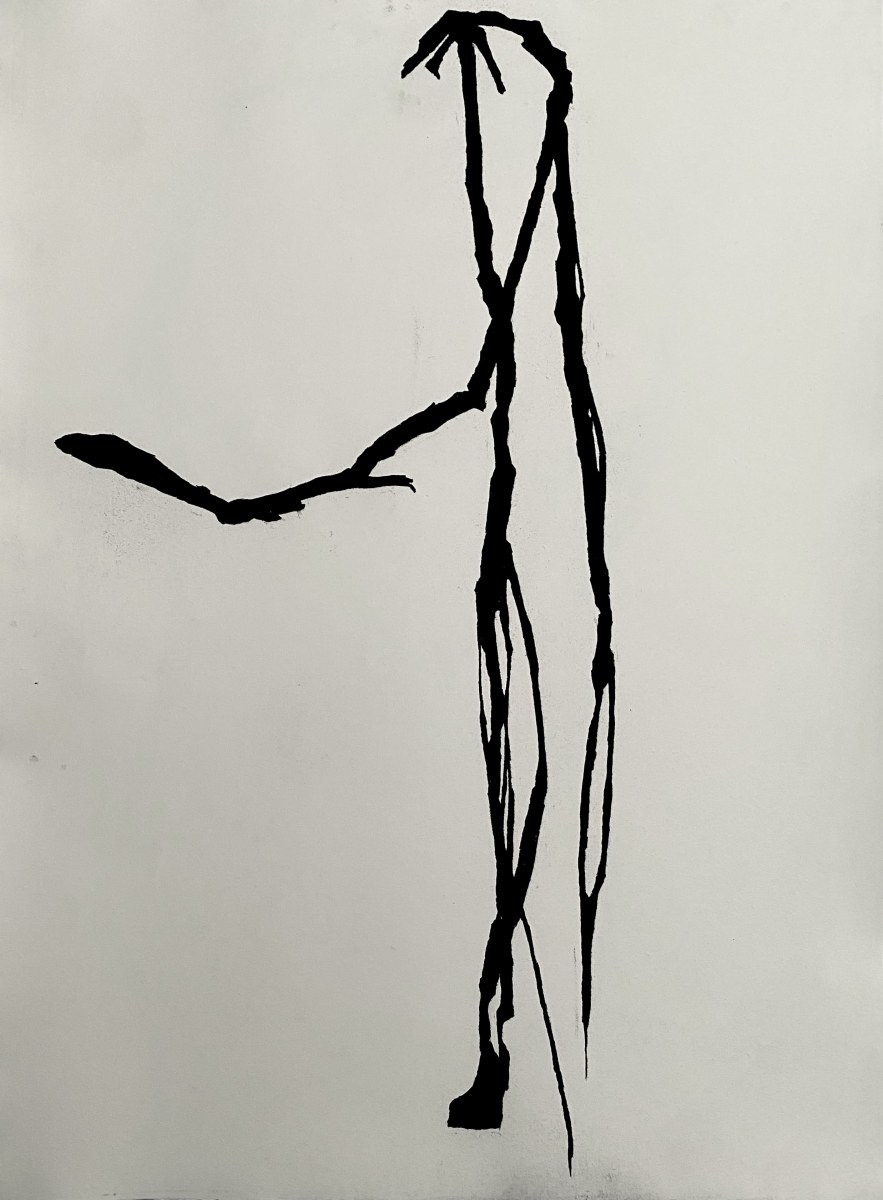

Bert de Geyter, With amazing grace, 2023, Settantotto Art Gallery

Some artists regard their studio as purely functional, while others consider it sacred. How do you view yours?

Every studio is practical because this is where work is carried out, but it’s much more than that. Above all, it’s my universe. It’s not necessarily where everything originates—much of that happens during my walks—but it’s where ideas and observations take form. Time as we know it doesn’t exist in this space; instead, it becomes what Joke Hermsen calls Kairos time. This ‘in-between space’ is essential for experimentation and being fully immersed in the act of creation.

The works in Fieldworks originate from your series Mnemosyne, which is based on observations of branches in a nature reserve where you frequently walk. Is proximity to nature essential for your studio or are natural light and other factors more critical?

To me, it’s essential. I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else in Ghent. I need to be outdoors and having a beautiful nature reserve nearby is invaluable. I’m grateful for it each and every day and visit it at least once a day. These walks are endless exercises in learning to observe, see and understand. They also serve as both a generator and filter for ideas and thoughts, a meditative state in which ideas form, disparate thoughts converge or slowly crystallise.

Natural light is also invaluable for the studio, especially twilight, when everything is briefly ‘in-between’, allowing me to see whether or not a work has reached its destination.

Studio Bert de Geyter. Courtesy Bert de Geyter

How did you approach this series? Do you take pictures while walking or do you rely on memory?

I work intuitively, but always based on observation. This, I believe, shows respect for the things around me. By repeatedly looking, I gradually learn to see, know and understand my surroundings. This requires care, which nature effortlessly demands.

The series title Mnemosyne refers to both a titan in Greek mythology and a river in Hades. Are you referencing the latter?

Both, since they are inseparable. Mnemosyne personifies memory and is said to have invented words and language. I particularly enjoy the notion of it being a river in the underworld. Drinking from other rivers in Hades makes you forget earthly life, but drinking from Mnemosyne allows you to remember and be remembered.

My work resonates with this undercurrent, addressing existential themes like life and death, connecting what is timeless and universal. As I state in a piece from the Out of Love series, “We are not the same, we are not different.” This series was inspired by the extreme drought of summer 2022 and the textual elements in my work, evolving as a new script or language. Emerging from nature’s constant flow, it places memory at its centre, always renewing itself. Mnemosyne ultimately became the focus of the series.

Bert de Geyter, Mnemosyne, 2022, Settantotto Art Gallery

The Out of Love series contains humour and uplifting elements despite heavy themes like loss and death. How did this combination originate?

It’s strange how discussions of death and loss are reflexively labelled as sad, heavy or dark. While this view aligns with today’s fast-paced, perpetually cheerful mindset, I am opposed to masking or avoiding the essence. I strive to confront life openly and wholeheartedly, without filters.

Yes, my work deals with loss and death, but these are integral to life. Unlike the Western view in which death is part of life, I view it the other way around. Life is part of death—the infinite energy source from which all life emerges and to which it returns. It’s gravity, with life as a burst of that energy following an elliptical arc between departure and return. While we can’t control the journey’s duration, we can influence its quality through lightness. I aim to hover just above the ground. This intertwining of death and life, letting go and radical acceptance defines my work. It stems from who I am and what life has made me. It’s another exercise in observation, meticulously transformed. A pivotal day—literally and figuratively a ‘in-between space’—where life and death are completely aligned, was a point of no return. It’s when I realised I was home and could finally let go and play.

My studio is also an ‘in-between space’. My studio is where I play with my inner child. Although it’s deeply existential and not free of obligation, it is still play. It’s a perpetuum of hope. Like me, my work has grown slowly into itself. Today, I can say, “I am my work; my work is me.” That brings a sense of peace. Over time, colour has disappeared from my work, leaving only the essence. Text became urgent, suddenly necessary. Ultimately, my work is not dark, but is always about light. “I use black for the beauty of daylight.”

Studio Bert de Geyter. Courtesy Bert de Geyter

Later this month, Settantotto will have a solo stand featuring your work at Art Antwerp. Which series will visitors be able to see there?

The Out of Love series, created this summer in which abstraction and text intersect. The collection includes work on paper in three sizes and large canvases. Some pieces are purely textual, while others combine depths (I wouldn’t call them surfaces) with fragments of text.

The series is about love. Though it appears dark, like all my work, it centres on light—embracing vulnerability to let light in. Without vulnerability, there is no love; without love, no light. It also explores the idea of letting go—an essential aspect of love. Oh, and I’ll be presenting a new neon work. In my opinion, it’s just as funny as the first if you read it on the right level.

If given unlimited resources, what project would you like to start on?

Because of the size of my studio, I can’t work spatially unless provided with a venue or resources. But I have ideas for large-scale spatial works. If I could choose two, I’d focus on Temple of Light and Monument for a Rainbow. A blueprint and section of the former hang in my studio, while I’ve made a cute miniature version of the latter using wooden wedges.

What are you currently working on?

I’ve just finished a series I began during a residency in Lanzarote, but couldn’t complete because I ran out of paper. What comes next? Tomorrow will tell.

Bert de Geyter. Photo by Yves Drieghe