22 october 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

The studio of... Roeland Tweelinckx

In a society increasingly oriented towards functionality, efficiency and rules, uselessness is becoming more and more obsolete. But Roeland Tweelinckx sees beauty in the useless. In Bending the rules of functionality, he transforms functional, everyday objects into non-functional ones that encourage reflection. The result is playful and humorous. An online review of Tweelinckx's work aptly sums it up: "Your work makes me laugh and think at the same time."

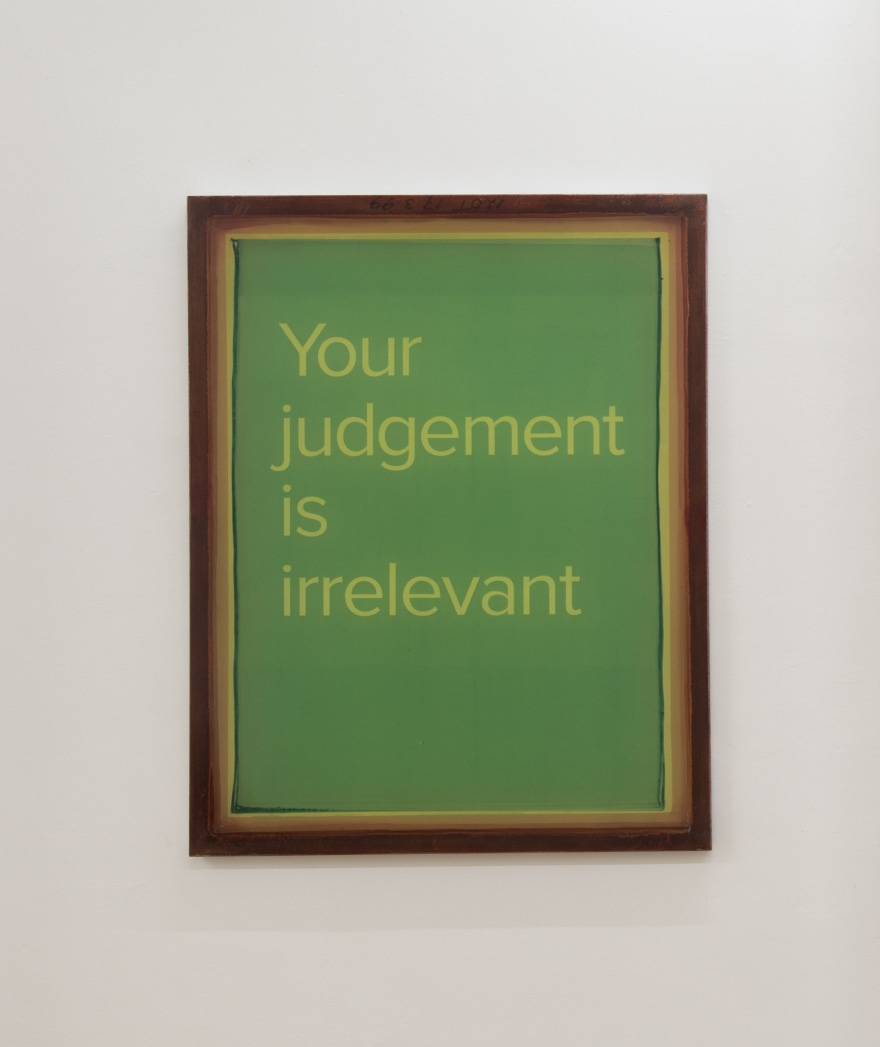

In Bending the rules of functionality, the exhibition that can still be seen this week at Eva Steynen Gallery, we see, among other things, a chair facing a white wall, a power cord standing upright and a screen-printing frame with the text Your judgment is irrelevant. With this last work, Tweelinckx aims to show that it is not always necessary to have a judgment, let alone make it public. “It’s more of a conclusion than a conscious choice. Whether you find the work good or bad is not important to me as an artist.”

We spoke to Roeland Tweelinckx about his studio, working method and the importance of the ‘photographic second’.

Bending the rules of functionality can be seen at Eva Steynen Gallery in Antwerp through 26 October.

Where is your studio and what does it look like?

My studio is next to my home in an old carpentry workshop of 180 m² at the back of my garden. It’s a rectangular space with lots of natural light thanks to a glass roof. I have divided the space into two sections: all my material and workbenches are along one wall and the other side is an empty, white space where I display my work. On this white wall, I have no distracting elements, only the work I am focused on, so there’s a nice balance between chaos and calm.

Roeland Tweelinckx, Stack of heatings, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery

For some, a studio is a workspace. For others, it's a private space where they can be themselves. Still others describe it as a sanctuary. How would you describe your relationship to your studio?

My studio is my personal space. I don’t just let anyone in. Apart from people from the art world, only my children, girlfriend and close friends are welcome. I love being in my studio and can experience immense joy from working there for hours on end—or as my kids used to call it: ‘crafting’. A huge advantage is that the studio is behind my house, so I can come and go whenever I want: early in the morning, late in the afternoon or even in the middle of the night.

Suppose you had to find a new space tomorrow. What would that new space absolutely require?

That new space would need to be at least as large, or even larger, than my current studio because I love having space around me. More storage space would also be welcome and it would be great if there was a direct access gate for transport, because right now, I have to carry everything through my house. And if it could also be in an idyllic, wooded place like the Ourthe Valley, I would be very pleased.

Roeland Tweelinckx, Looks like a rope, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery

Congratulations on Bending the rules of functionality! Why do you want to bend or stretch the rules and what do you hope to achieve by doing so?

As an artist, I find it important to critically examine our society, which increasingly revolves around rules and expectations in relation to them. I also get the impression that everything has to be functional. But there’s much beauty in uselessness or the act of being useless. By transforming functional, everyday objects into non-functional ones, I want to encourage the viewer to reflect and engage in dialogue. I don’t use objets trouvés, but rather experiment with trompe-l'œil and reproduction. The functionality of the objects is irreversibly lost in my work.

Like the title of the show suggests, your work reveals a subtle sense of humour and playful approach to reality. That’s something many artists avoid. When did you realise that this, too, is part of your work?

Recently, I received the shortest essay about my work ever via social media: “Your work makes me laugh and think at the same time”. Humour is a common thread in my life. It plays a crucial role in who I am as a person, artist, partner, father and friend. It would be odd if I didn’t carry this aspect into my artistic practice. Although humour has always played a role in my work, it took some time before I fully embraced it. During my very serious education at the academy in Antwerp, there was little room for humour. We mostly learned that art was serious. After graduation, I continued my education abroad, where I learned how to put things into perspective. Along the way, humour slipped into my work. A work of art can be full of humour and still be created with utter seriousness.

Roeland Tweelinckx, Darts, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery

Which artists do you feel connected to?

That’s a difficult question because there are so many great artists. I feel particularly connected to artists who are true to themselves and make honest work. If I had to name a few, that would be Henk Delabie, Wesley Meuris, Just Quist, Niamh O’Malley, Fred Sandback and Marcius Galan.

Roeland Tweelinckx, Your judgement is irrelevant, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery

Let’s examine two works more closely. The first one is called Your judgment is irrelevant, a screen-printing frame with the somewhat confrontational title. Why is our judgment irrelevant?

With Your Judgment is Irrelevant, I want to show that it’s not always necessary to have a judgment, let alone express it. It’s more of a conclusion than a conscious choice. Whether you like the work or not is not important to me as an artist. I create primarily for myself. Once the work leaves my studio, it stands on its own and it's fine if it doesn’t resonate with everyone. What I find most interesting is that it evokes something in the viewer. It’s also a bit of a game with the audience; at the opening, someone came to tell me that the typography wasn’t right.

Roeland Tweelinckx, In a fit state, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery

Another work that stays with you is called In a fit state and consists of two power cords, one of which is standing upright. Where did this idea originate? Personally, it made me think of a cobra, but I think you always start with the material properties of an object and the expectations we have of them. Is that correct?

This idea came to me during an intense and inspiring residency in Lisbon last spring, where I wrote down around 120 ideas on paper. I call this process the registration of ideas. The work quickly came to mind when I saw a power cord lying on the floor. In a split second, I added an upright element to my mental image to detach it from reality. This is how most of my work originates: it suddenly appears in my mind. The underlying philosophy can be approached in various ways. It’s not just about the material properties, though those sometimes play a role. One of the layers is what I call the ‘photographic second’: the moment the cord is released and falls down, capturing that moment. My work is always layered and whatever you see or feel is perfectly fine. There is no single way to approach it.

Besides sculptures, Bending the rules of functionality also includes several interventions in the gallery space. Supposing you could choose any space for interventions, is there a space you would like to work with?

Interventions remain the most interesting thing for me to do and are truly the essence of my work. The ideal space doesn’t really exist for me, although I am often fascinated by the possibilities in many places, whether it’s a white cube or a raw space. Perhaps I would most like to build the ideal context myself: a box within a box. Together with my good friend and architect Peter Gillis, I’ve been working on such a project for some time. It would be amazing to create a museum space consisting of several successive rooms, so you don’t have an overview, just like when walking through a forest, curious about what’s around the next bend.

What are you currently working on?

I’m always working on several projects at the same time. Right now, I’m working on a new series of ‘unconscious dust drawings’ and trying to spend at least an hour a day in my studio or just being present. Together with my friend and designer Hans Van Den Eynde, I’m also preparing a new publication. I’m also organising a duo exhibition that will open on 9 November at Violet (Art Space) in Antwerp together with artist Sebastien Pauwels.

Roeland Tweelinckx, Wall and chair, 2024, Eva Steynen Gallery